The Spectator: Mao's Music

It’s early in the year but there is unseasonal heat as hundreds of earnest young musicians gather to learn from artists of the Silk Road Ensemble... Fostering innovation in China, a country hindered by an educational system that encourages rote learning and discourages asking questions, is not always easy. Some classical musicians have broken through: concert pianist and child prodigy Lang Lang is a celebrity here, commanding sell-out concerts and legions of fans. But Long Yu, the man who has helped spearhead China’s classical music renaissance (he is artistic director and chief conductor of the China Philharmonic Orchestra and music director of the Shanghai Symphony) wants more.

The Spectator

By Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore

Smog is making me cough and I feel my eyelids smart and redden. High-rises are swaddled in a soupy haze and locals scuttle about their day, huddled against the cold, faces down. Has Beijing done nothing to improve pollution since I last lived there three years ago? This is a city that changes fast. There are the same old scruffy nail bars and lamb hot pot restaurants, the windows smudged with steam from boiling vats of oil and meat. But in the ancient hutongs or alleyways there is also a smattering of Scandinavian-style design stores. Hidden around the back of one is a tranquil café, at odds with the dirt and dust outside, classical music wafting into chilly air. Here are the locals you never see on the street: men in elegant cashmere coats, scarfs slung around their necks; women propping Louis Vuitton bags against long, poised legs. I stop for a hot chocolate and avocado cheese cake; it costs nearly twenty dollars.

‘There is in fact no such thing as art for art’s sake,’ Mao Zedong said. Under the ‘Great Leader’, during the tumultuous tragic years of the Cultural Revolution, classical Western music was particularly despised as ‘bourgeois’. Instruments were smashed, concertos ripped up, and conductors punished, sometimes with death. When facing execution for tearing up Mao’s Little Red Book, Lu Hongen, conductor of the Shanghai Symphony, said to his cellmate. ‘Visit Austria, home of music. Go to Beethoven’s tomb and lay a bouquet of flowers. Tell him his disciple is in China.’ Would Lu laugh or cry if he went to Guangzhou now? I’ve taken the long train ride south to see the very first Youth Music Culture Guangdong (YMCG) in action, the pet project of Chinese-American superstar Yo-Yo Ma and the Guangzhou Symphony Orchestra. It’s early in the year but there is unseasonal heat as hundreds of earnest young musicians gather to learn from artists of the Silk Road Ensemble. Among the educators is symphony conductor Michael Stern. When his father, violinist Isaac Stern, made history by touring China in 1979, just three years after Mao’s death, he found not one playable piano left in Shanghai. His son has arrived in a new era: China is now the largest piano producer in the world, and the largest consumer too with some forty million students learning to play. Beethoven, it seems, is not short of disciples.

Yo-Yo Ma, a believer in art for art’s sake, relishes the redemptive qualities of creation. I ask him why here, why now? Why China? ‘When the flood gates open there’s this moment of receptivity. There’s a small window in this society where you can do so much,’ he says. He looks down at his hands, adjusts his shirtsleeves rolled half way up his arms. ‘I think if that window closes it’s going to be harder to start things, to create habits, cultural habits. For me, it’s planting seeds that we may not see the resultsof for twenty, thirty years.’

‘I want you to have enough courage to stand up,’ Yo-Yo Ma later tells a room of shy young musicians, bent over their instruments, anxious to do well and to please. ‘Who’ll be the first victim?’

Fostering innovation in China, a country hindered by an educational system that encourages rote learning and discourages asking questions, is not always easy. Some classical musicians have broken through: concert pianist and child prodigy Lang Lang is a celebrity here, commanding sell-out concerts and legions of fans. But Long Yu, the man who has helped spearhead China’s classical music renaissance (he is artistic director and chief conductor of the China Philharmonic Orchestra and music director of the Shanghai Symphony) wants more. ‘Asian parents, they force the kids to learn instruments not to introduce arts to them but they want to train them to become a star, the next Lang Lang, or to add some points when they apply to university. But this is totally wrong,’ he insists. ‘We don’t need only one or two champions. We need a new generation to understand creativity.’ Some are rising to the challenge. Back in an improvisation workshop, under the cold glare of classroom lamps, a plump girl in a yellow frilly dress shakes her hips, forgetting the glasses that fall down her nose, while a percussionist taps out an addictive beat. Yo-Yo Ma is happy. His charges are starting to stand up, no longer victims. As he confides with a grin, there is a little known secret: ‘You can practise imagination’.

Strings Magazine: Yo-Yo Ma and Silk Road Ensemble Members Team Up with Maestro Long Yu for Inaugural Youth Music Culture Guangdong

Ma is in Guangzhou, historically a major terminus of the Silk Road in the Guangdong province of China, acting as the artistic director of Youth Music Culture Guangdong—a program in its first year designed to shake up 80 young musicians with a flurry of chamber-music coachings, Silk Road Ensemble–style workshops, panel discussions, and two final concerts, where participants perform as chamber-music groups and as an orchestra.

Strings Magazine

By Stephanie Powell

Music director Michael Stern fervently bounces along to Beethoven’s Symphony No. 8 as he leads the string section of the orchestra. Stern pauses to offer thoughtful direction to the violins on breathing with their bows and asks the violas to sing into the cello section—and, also, to lighten the mood. “It’s joy,” he says of the passage in the score, “and it’s also just noise, right?” Laughter erupts. About 45 minutes into rehearsal, someone slips in through a side door. The students are so focused on the repertoire at hand they don’t notice.

But I take notice of the tip-toeing man, with Jacqueline de Pré’s 1712 Strad in hand, headed toward the last seat in the cello section—it’s Yo-Yo Ma. He shares a music stand and dives right into the Beethoven.

Ma is in Guangzhou, historically a major terminus of the Silk Road in the Guangdong province of China, acting as the artistic director of Youth Music Culture Guangdong—a program in its first year designed to shake up 80 young musicians with a flurry of chamber-music coachings, Silk Road Ensemble–style workshops, panel discussions, and two final concerts, where participants perform as chamber-music groups and as an orchestra.

The program is the brainchild of Ma, who tapped veteran orchestra players and some of his fellow Silk Road Ensemble members to join him, and maestro Long Yu—a powerful, almost single-handed force in China’s

classical-music scene. He holds director-level positions in multiple orchestras across the country, is the founder of the Beijing Music Festival, and much more. The participants, who together make up the YMCG orchestra, are between the ages of 18 and 35, and are all of Chinese descent from Guangzhou or neighboring provinces, Europe, and the United States.

Violinist Johnny Gandelsman coaches a group of YMCG participants on Beethoven’s Septet in E-flat major, Op. 20. Photo by Liang Yan

The two-week-long program takes place at the Guangzhou Symphony Orchestra’s rehearsal hall, located idyllically adjacent to the Pearl River. The hall is surrounded by a jagged skyline of metallic skyscrapers and cutting-edge architecture, and the backdrop proves a perfect setting in which to explore the juxtaposition of new and ancient.

And exploration is exactly what Ma has set out to inspire. He’s not there to perform the Beethoven with the orchestra, which is billed on the final-concert program (though he can’t help but sit in and discuss the intricacies of the symphonic work with inquiring minds during rehearsal breaks). He’s there to take trained, technically proficient musicians on a journey to tackle the unfamiliar.

The faculty selected to help the students on that journey includes violinists Johnny Gandelsman and Shaw Pong Liu; cellist Mike Block; oboist Liang Wang of the New York Philharmonic; clarinest/composer Kinan Azmeh; trumpeter Bill Williams; percussionist and Silk Road associate artistic director Joseph Gramley; 22-year-old yangqin player Reylon Yount; singer/sheng virtuoso Wu Tong, and Harvard researcher Tina Blythe. Michael Stern, music director of the Kansas City Symphony and son of violinist Isaac Stern, takes charge as music director of the YMCG orchestra.

Yo-Yo Ma and Long Yu speak during a YMCG panel discussion. Photo by Liang Yan

With the upswing of growth in China’s classical-music scene, it’s no surprise this powerhouse team found its way here. From the inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition, which took place last January, to the opening of Juilliard’s first satellite campus in Tianjin in 2018, there is undoubtedly a driving force in China’s classical-music scene that feels like it’s only continuing to build momentum. Concert halls are popping up all around the country: Construction of the China Philharmonic Hall is set to finish in 2019, and will offer the country’s philharmonic its first permanent (and translucent) 11,600-square-meter home. It’s hard to ignore the buzz—but why Guangzhou? I ask Ma and Yu—and they each credit the other for the idea.

Guangzhou was the first Chinese port open to foreign traders and was a stop on the Silk Road—offering a convergence of cultures. “Guangzhou is a very interesting place,” Yu says. “It’s very open-minded and young people come here from all over China—from Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin—not just the Guangdong province.”

This sense of diversity is central to the YMCG experience. “What’s interesting is that there are people here from all the different Chinese cultures, from all the provinces,” cellist Mike Block says, “so, there’s this internal energy. It seems like it’s important that the participants are all here together.”

Chinese conservatories have a reputation for producing musicians with razor-sharp technique, which is apparent during any rehearsal. But conservatories also tend to place a heavy emphasis on orchestral works—programming that YMCG challenges with daily chamber-music coachings and improvisation exercises. “Education in China is a valid [topic] to be discussed—not only in China, but all over the world,” Yu says. “For this program, the most interesting [aspect to me] is opening more windows in the mind. [Showing participants] different ways to see—how you could be; how big the possibilities are as a person. You can change yourself. That is more important than only playing onstage. We can find thousands of talented players who are technically perfect, which [can be important], but I don’t want to see a perfect, technical machine onstage—I want to see a person full of life.

“[Playing] music is like having a conversation with a friend, and if the [participants] are learning that—to have that joy, that conversation—that’s the reason that we are doing this. To understand more meaning in life. Yo-Yo has such a big heart; he brings all the young people to another world.”

“Are you a comet?” Yo-Yo Ma asks a group of wide-eyed violists after they play a passage of Bach’s Concerto for Violin and Oboe in C minor. He pauses. “Are you a planet? Are you an alien?”

The blank stares continue, and then some laughter, as he tries to elicit excitement from the violists after a technically sound performance that still seemed to lack full heart. “This is the viola’s revenge,” he assures them. “We, too, are stringed instruments! This is your moment!”

This is a typical exchange during Ma’s chamber-music coaching sessions—he uses out-of-this-world metaphors, swaying along with the music, occasionally demonstrating on instruments, communicating in confident Chinese (albeit needing occasional backup on a few words, like “sister-in-law”), and with his breathing and body language.

Ma is in fact so committed to effective communication that his body language almost betrays him during a rehearsal of the Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor with the YMCG orchestra. Stern and the participants are lost in the moment, moving so quickly through the music that Ma, bowing up front on the podium, leans so far forward that Stern has to grab him to keep him from toppling over.

During my first day observing chamber-music sessions and Silk Road workshops, I can see bemusement in the participants’ eyes. This isn’t about perfecting intonation or achieving technical accuracy—it is about finding freedom in the music, and revealing a part of themselves. “Today I said to the section leaders, ‘Look, your job as section leader is to communicate energy, character, gesture,’” Ma says. “And you have your back to everybody, so your shoulders—you have to communicate through that frame. If you want to communicate life, you actually have to look at your body space for what it is—and then, you actually have to exceed it.

“Think of air and boiling water,” he says. “If you’re a pot with a lid on it, the water’s cold, the air takes up a certain amount of body, and once it heats up, [the lid] starts to pop—that’s what you have to do. You have to show what is expected of you, and then you actually have to go further.”

This is not a school, Ma says of YMCG, “but what I love about it is that it’s what a school could be.” The model is simple—start out with a diverse faculty with varied skillsets, but similar values. “We don’t say, ‘Oh, this is the way to teach,’ but through those values, we sign on to sort of say, ‘OK, how can we do a 360 on music? How can we acknowledge different styles of music in large-group playing, and how do you take it to small groups?’”

The results are transformative. The participants’ schedule is jam-packed—the day starts at 10 am with a three-hour orchestra rehearsal, which is usually punctuated with laughter in between demanding passages, thanks to Stern and Ma’s witty banter. Chamber-music rehearsal follows for two hours before a Silk Road workshop. A panel discussion that melds music, philosophy, innovation, and tradition caps off the day.

Yo-Yo Ma sits in the back of the cello section during orchestra rehearsal at YMCG. Photo by Li Lewei

“What I like about coaching is helping the participants figure out what’s in the music. It’s kind of like music archeology,” violinist and Silk Road Ensemble member Johnny Gandelsman says. “Sometimes, if you don’t have a lot of experience with playing chamber music or looking at the score, you might not realize how special something is, so I like working with the groups on details, and helping them discover things for themselves.

“And then, once there is that moment of recognition, of, ‘Oh, I get it!’ That’s really rewarding—they’re excited about the music,” he says. “And now they have tools to succeed: to know how to listen to each other, how to look for unified sound. Building trust and having these building blocks that they can then take into their lives when this is over.”

About a quarter of the participants are professional musicians, Gandelsman says, holding positions in some of China’s most well-respected orchestras. Others, Ma later tells me, aren’t necessarily studying music performance or have aspirations of becoming professional musicians. One works as a physicist, and had about three years of violin lessons in his youth. Since then, he’s been essentially self-taught (which seems impossible upon hearing him play) and more than anything, he always wanted the opportunity to perform Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite with an orchestra. YMCG is his chance.

The Silk Road workshops are unmistakable highlights for the faculty and participants. On the first day of the workshops, the students choose one of six Silk Road tunes as a place to start, and they then have to improvise. Walking through the GSO during the workshops, I hear music singing from each corner that sounds like it comes from both the center of the earth and the beginning of time.

Block, director of Silk Road’s Global Musician Workshop, heads the workshops at YMCG. “Apparently the way that classical music is taught [in China] is very regimented,” Block says, “and the same can be said about American classical teaching. The warnings that I got were that it was somehow even more regimented here. So we were unsure how the participants would react to the Silk Road–band opportunity, and I felt from the first session I had with them that they were really no different than American classical musicians. They had various walls that we wanted to break through, but across the board they rose to the occasion.”

Cellist Mike Block coaches a chamber group before a YMCG “Tomorrow Concert.” Photo by Liang Yan

Block has led similar workshops with Silk Road’s Global Musician Workshop across the United States—even at Tanglewood last summer. Leading workshops in such strict orchestral arenas, like YMCG, can be challenging, he says. Typically the workshops take place in an environment where the participants are choosing to be there because they want to improvise and want to be creative. “I’m coming into an orchestral environment where participants aren’t necessarily expecting or planning to improvise, and that’s a very different environment to do this work in,” he says. “Yo-Yo is very passionate about taking those values and bringing them to people who don’t know they need them, or don’t know they value them yet. So, that’s a big part of why I’m here—to have this experience with them.”

There are three nights of final concerts, two chamber-music and one orchestral, that demonstrate the transformative power of this program. The final orchestral performance is energentic and fearless—the orchestra members distinguish themselves with a performance delivered with a contagious sense of enthusiasm and confidence. It is an exhilerating evening, and what one might expect given the participants’ intensive orchestral training.

A chamber group takes in the audience’s response after a triumphant performance of a Silk Road–style arrangement during a Tomorrow Concert. Photo by Liang Yan

But throughout the program, students have also been preparing two sets of chamber-music works for YMCG’s “Tomorrow Concerts.” The concerts take place over two nights—dividing the participants into two sets of chamber groups. In the first half of each Tomorrow Concert program, chamber groups perform a piece of standard repertoire from Debussy to Bach to Steve Reich. In the second half, participants perform works they arranged and composed in the Silk Road workshops. After witnessing a handful of the workshops myself, I think I have a sense of what to expect.

I have, after all, watched the participants work through incorporating unnatural playing techniques and sounds into their compositions—like using the violin as a percussive instrument, fumbling awkwardly with unfamiliar instruments, and interspersing their arrangements with vocals and choreography. The participants’ skills and confidence grew, and it feels obvious. But the transformation that takes place overnight from rehearsal hall to the stage still manages to leave me, and the audience, speechless (figuratively).

During each half of the Tomorrow Concerts series, personality, humor, and confidence shine through the seven groups vibrantly. They take turns owning the stage, breathing together, looking at each other during passages that require dialogue between instruments, and leaning into one another during the standard-repertoire section. The Silk Road–workshop pieces deliver such freedom and variety that the faculty can’t help but shout, yell, stand, and clap after—and during—each performance.

The concerts demonstrate an assortment of explosive cello chopping, solid percussive techniques, stunning vocals, a little shimmying around the stage, and even Mission Impossible medleys.

A violist from the second group grabs the microphone and addresses the faculty, who are all sitting together in the audience. “This has been . . . ,” she says, and pauses, “so damn hard.” The faculty cheers. “We’re going to show you what is courage, what is brave, what is happy.” She then looks into the crowd for the participants who performed in the previous night’s Tomorrow Concert. “Group A—you asked for this,” she says before her group jumps into an electrifying performance.

The energy in the hall instantly changes from polite and attentive to a rowdy musical party. At the close of the final group’s performance, the faculty stands up to give a standing ovation, and you could sense that a door had opened for these students, and they had just started to walk through.

“I still remember the first day when all the [participants arrived],” Yu says. “I saw their eyes, their confusion—you know, they [didn’t] understand what was going on. [Many came] here because of Yo-Yo, but then they realize later that it’s not only Yo-Yo himself, it’s also the things that he brings to them . . . I saw all of their eyes onstage shining with a lot of confidence, a lot of fun, and they finally know why they [are playing]. Today, they became [alive].”

Despite coaching many of the groups, Block says, they still had the ability to surprise him. “For the performers who played during both halves [of the Tomorrow Concerts], it seemed like they were able to access different parts of themselves for the different types of music—and that is really exciting.”

Even Yu admits a slight bias for this project—after more than 20 years of advocating for and advancing the classical-music scene in China—and that says a lot. “YMCG will help the future generation,” he says. “Yo-Yo and I have both talked about this—he’s over 60 and I’m over 50—and for us, for the rest of our lives and careers, the most important [task] is how to help young people.

Yo-Yo Ma after a performance of Dvorak’s Cello Concerto with the YMCG orchestra. Photo by Li Lewei

“It’s my life—music is my language. I tried working for 20 years to help China make a lot of things happen, and a lot has worked. Today [classical music in] China [is] so different than when I came back from Europe. I’m very proud to say we’ve made huge musical changes. [With YMCG], Guangzhou has now opened a new window—[one] that we can now explore for other musicians in China.Creativity and imagination—those are two words that are now very important for young musicians in China.”

The passion is tangible, and (in my case) even tear-inducing. “I think there are as many ways to awaken passion as there are people because it’s so individual and you can’t just say, ‘I want passion!’ It’s something that happens I think when people are using all of themselves,” Ma says. “What makes people remember something forever? What happens I think is, when you are maximally open to something, and you meet a different world, you will maximize the moments with that passion.”

When I ask him for his final impressions of the participants’ Tomorrow Concert performances of their Silk Road arrangements, he replies, “That’s a big victory moment.

“They’ve self-identified. That’s what we hope for. Because you can build from that. Nobody’s going to ever forget what they did. They can forget all we’ve said—all the [orchestra and chamber music] we played—it doesn’t matter. But if they build from those performances they’re in good shape—[they can remember] ‘we used all of ourselves to say something that we really wanted to say.’”

YMCG music director Michael Stern during the final orchestra concert. Photo by Li Lewei

Financial Times: Youth Music Culture Guangdong, Xinghai Concert Hall, Guangzhou

A gathering of young musicians came to life when the players left their comfort zone.

Financial Times

By Ken Smith

A gathering of young musicians came to life when the players left their comfort zone.

Read the full article on the Financial Times website.

Banner image photo credit: Li Lewei.

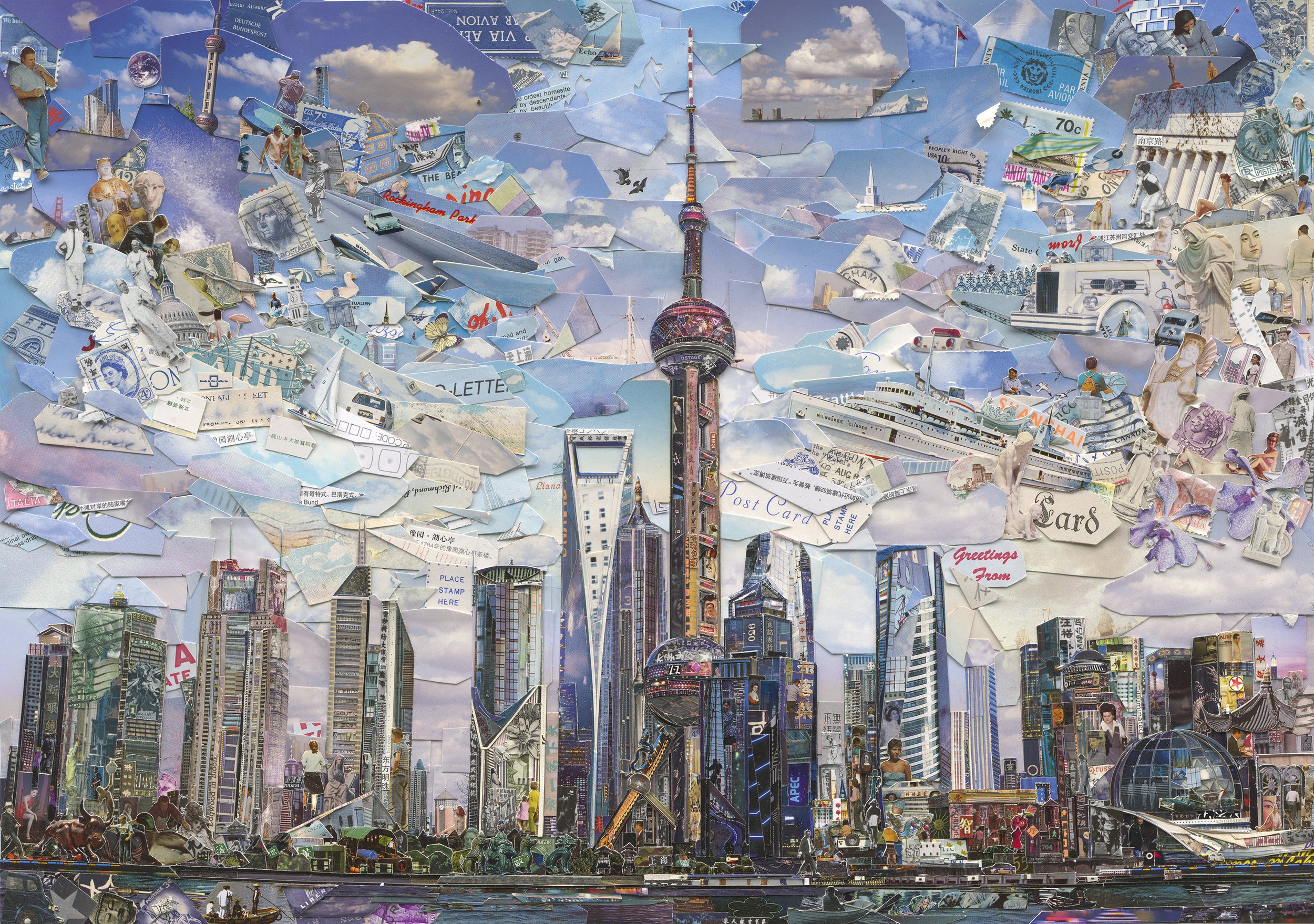

The Strad: Postcard from Shanghai - Competing with the Traditional

The SISIVC is one of a number of music competitions to have sprung up in Asia over the past few years; with a $100,000 first prize, its inaugural edition this August [2016] attracted high-level performers from 26 different countries.

The Strad

December 2016 issue

By Pauline Harding

"All around me, bamboo-like slates rise up to a ceiling made from giant, woven strands of what looks like flax; horizontal strips of wood demarcate different floors. I could be sitting in a giant dim sum basket - but in fact it is Shanghai's Symphony Chamber Hall, where I am awaiting the first contestant in the final section of the Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition (SISIVC) semi-final. And indeed, things are about to heat up, as 18 contestants prepare to perform Mozart's Third Violin Concerto, all with their own cadenzas...."

Purchase The Strad for the full article, here.

Strings: Conductor Long Yu, Cellist Yo-Yo Ma, and Sheng Virtuoso Wu Tong Tour the Gobi Desert

This September, conductor Long Yu, cellist Yo-Yo Ma and sheng virtuoso Wu Tong embarked on a four-city tour of China. The tour kicked off with the Hong Kong Philharmonic’s season opening concerts on September 9 and 10. The three then traveled to Xi’an for an open-air concert at the old city wall on September 12 and reprised the work on September 15 at Lanzhou’s Jincheng Theatre and on September 17 at Ürümqi’s People’s Grand Hall.

Maestro Long Yu provided Strings magazine with an exclusive look and commentary on the tour, which marked the first time many of these cities had ever seen Yo-Yo Ma perform in person.

Strings Magazine

This September, conductor Long Yu, cellist Yo-Yo Ma and sheng virtuoso Wu Tong embarked on a four-city tour of China. The tour kicked off with the Hong Kong Philharmonic’s season opening concerts on September 9 and 10. The three then traveled to Xi’an for an open-air concert at the old city wall on September 12 and reprised the work on September 15 at Lanzhou’s Jincheng Theatre and on September 17 at Ürümqi’s People’s Grand Hall.

Maestro Long Yu provided Strings magazine with an exclusive look and commentary on the tour, which marked the first time many of these cities had ever seen Yo-Yo Ma perform in person.

September 9/Hong Kong: The first concert of the tour with the Hong Kong Philharmonic (opening concert of the 2016/17 season). Yo-Yo Ma joined the HK Phil and myself for Dvorak’s Silent Woods, and then took the stage with sheng virtuoso Wu Tong for Zhao Lin’s Duo.

Inspired by the Chinese epic Journey to the West, Duo was composed for sheng player Wu Tong and Ma. It is a partnership of two lyrical instruments with liquid, expressive sounds.

September 11 / Xi’an: Rehearsal at the historic “South Gate” at the Old City Wall in Xi’an in Central China. Xi’an marks the Silk Road’s eastern end and was home to the Zhou, Qin, Han and Tang dynasties’ ruling houses.

September 12 / Xi’an: Everyone is preparing their own Yangrou Paomo (flatbread soaked in lamb soup).

September 12: / Xi’an: Oh no! It’s raining! We hold an emergency meeting to decide whether to cancel the outdoor concert.

September 12: / Xi’an: 40 minutes later, the rain stopped and things are just perfect!

September 13 / Dunhang (Gansu Province): We’ve traveled to the edge of the Gobi Desert to the city of Dunhang. Once a frontier town on the Silk Road, the area is known for its caves, cliffs, and Buddhist statues.

September 13 / Mingsha Shan (Singing Sands Mountain) in Dunhuang: Mingsha Shan is about 5 miles from Dunhuang. Seen from afar, the mountain is just like a golden dragon winding its way over the horizon. At first, the sand under your feet just whispers; but the further you slide, the louder the sound until it reaches a crescendo like thunder or a drum beat. Some say that the sand is singing, while to others it is like an echo and this is how the mountain gets its name. We wore these bright orange “boots” to keep the sand out from our shoes!

September 14 & 15 / Lanzhou: A wonderful concert with the Lanzhou Symphony Orchestra. The audience was so appreciative of the playing and we were so appreciative to be here! Wu Tong performed an encore afterward and Yo-Yo and I sat and watched. As you can see, Yo-Yo didn’t want to stop listening!

September 16 / Ürümqi: We traveled more than 2,000 miles today from Lanzhou to the Northwest city of Ürümqi—another former major hub on the Silk Road. Upon arrival, we rehearsed with the Xinjiang Philharmonic Orchestra. The XPO was founded in 1996 and is made up of many ethnic groups, including Han Chinese, Uyghurs, Hui, Kazaks, Tajiks and Xibe. So many different languages and cultures but they come together through music in complete harmony!

September 17 / Ürümqi: Final concert of the tour. It’s hard to say goodbye to dear friends like Yo-Yo and Wu Tong but we ended on a high note and look forward to making music again soon.

The New York Times: Shanghai Violin Competition Celebrates Isaac Stern’s Legacy in China

The inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition concluded on Friday after nearly three weeks of intensive performances by 24 young violinists from around the world. Mayu Kishima of Japan was awarded first place, taking home the grand prize of $100,000, the largest single award for an international violin competition.

The Japanese violinist Mayu Kishima was awarded the first prize at the inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition on Friday. Credit: Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition

The New York Times

By Amy Qin

More than 35 years after the violinist Isaac Stern made a groundbreaking visit to China, his legacy there lives on.

The inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition concluded on Friday after nearly three weeks of intensive performances by 24 young violinists from around the world. Mayu Kishima of Japan was awarded first place, taking home the grand prize of $100,000, the largest single award for an international violin competition.

“We were looking for the kind of spark and commitment to music that our father would have embraced,” David Stern, co-chairman of the jury committee, said in a telephone interview from Shanghai.

That Isaac Stern, who died in 2001, now has a competition bearing his name is somewhat ironic given his aversion to such events.

So when the conductor Yu Long, a towering figure in classical music in China, raised the idea of holding a competition about two and a half years ago, “it was not the easiest idea for the three of us to approach,” Mr. Stern said, referring to his brother, Michael, and his sister, Shira. “Our father did everything he could to mentor young musicians in order to avoid competitions.”

Isaac Stern’s dedication to training young musicians was perhaps most vividly captured in the 1979 documentary “From Mao to Mozart: Isaac Stern in China.” The film, which won an Academy Award for best documentary feature, chronicled Mr. Stern’s two-week trip to China for a series of concerts and master classes.

That visit, which came just as China was emerging from decades of self-imposed isolation and political tumult, is credited with having influenced a generation of young Chinese musicians, including Mr. Yu, who recalled sitting in the audience as a teenager during one of Mr. Stern’s performances in Shanghai.

“During the Cultural Revolution, we didn’t have many opportunities to play Western music,” Mr. Yu, now conductor of a number of ensembles including the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, said in a telephone interview. “Then, in that moment in 1979 when Maestro Stern came, we suddenly felt the difference in how we could understand music.”

Since 1979, classical music in China has grown tremendously, with gleaming concert halls being built around the country and some 40 million young Chinese studying the violin or the piano.

Still, Mr. Yu said, “The problem in China, and Asia more broadly, is that the players are more concerned about technical issues.”

So when it came to this new project, both the Stern family and Mr. Yu agreed that they wanted to make a more comprehensive competition that would reward musicians not just for technical ability, but also for all-around dedication to music.

After two years of discussions and planning, the Stern family and the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra came up with a competition structure that David Stern said his father, even with his distaste for competitions, probably would have approved. This meant including elements that were important to Isaac Stern, like chamber music and Chinese music.

For example, contestants in the semifinal round were required to perform two concertos: “The Butterfly Lovers,” a popular Chinese concerto composed in 1959 by He Zhanhao and Chen Gang, and Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 3 with a chamber orchestra (with original improvisation during the cadenza section). They also had to play a violin sonata, as well as the first movement of piano trio by Schubert or Brahms.

The 24 contestants represented several countries, including China, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea and the United States. In addition to the prize money, Ms. Kishima will also receive performance contracts with several international symphony orchestras.

Sergei Dogadin of Russia was awarded the second prize of $50,000, and Sirena Huang of the United States took home the third prize of $25,000. The violinists Zakhar Bron of Russia and Boris Kuschnir of Austria were among the 13 who sat on the jury.

The competition also presented an Isaac Stern Human Spirit Award of $10,000 each to two noncontestants: One, to Wu Taoxiang and Du Zhengquan, who founded the Einstein Orchestra, a middle-school ensemble in China, and the other to Negin Khpalwak, who directs an orchestra for women in Afghanistan, for “their outstanding contribution to our understanding of humanity through the medium of music.”

Most of the funding for the competition, which will be held every two years, came from corporate sponsors, according to Fedina Zhou, president of the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra. The symphony has been expanding in recent years, forging a long-term partnership with the New York Philharmonic and, in 2014, unveiling a new hall where the competition was held.

For many musicians and music lovers in China, the competition represents further validation that China is well on its way to becoming a heavyweight player in the classical music world.

“At last the Chinese people finally have an internationally recognized competition of their own,” said Rudolph Tang, a writer and expert in Shanghai on the classical music industry in China. “It has everything that a top competition should have, like a top jury, great organization, and high prize money.”

“It is like a dream come true,” he added.

The Strad: Violinist Isaac Stern in China

Captured in the 1979 Academy Award-winning documentary From Mao to Mozart, Isaac Stern had a transformative effect on China's classical music scene - more than he ever knew. Today his legacy lives on with the launching of the Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition. Nancy Pellegrini talks to son David Stern and some of the film's stars about the 'Stern effect.'

The Strad

Excerpts from Violinist Isaac Stern in China

Captured in the 1979 Academy Award-winning documentary From Mao to Mozart, Isaac Stern had a transformative effect on China's classical music scene - more than he ever knew. Today his legacy lives on with the launching of the Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition. Nancy Pellegrini talks to son David Stern and some of the film's stars about the 'Stern effect.'

The year was 1979. Emerging from decades of isolation and political turmoil, China had just opened its door to the West, and legendary violinist Isaac Stern was hoping to peek inside. The result was the Academy Award-winning documentary From Mao to Mozart, which chronicles Stern's visit to music conservatoires in Beijing and Shanghai. This brilliant, touching film gave Westerners an insight into life behind the Bamboo Curtain, while igniting Chinese careers and changing music in China forever. The Stern family has continued its association with the country, but it is China that will never forget. August 2016 was the start of the inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition (SISIVC), which organisers hope will help to inspire and motivate a new generation of musicians.

Isaac Stern had long used his musicianship to build bridges and foster talent, touring the Soviet Union in 1951, helping save New York’s Carnegie Hall from destruction, and mentoring a host of promising young players including Itzhak Perlman, Yo-Yo Ma and Pinchas Zukerman. While some claimed his extra-musical efforts were hampering his own skills, music and humanity were, to him, simply extensions of each other. China opening up to the West was his next logical frontier.

However, when even US diplomat and close friend Henry Kissinger couldn't help him gain entrance, Stern had a strategically casual dinner with China's foreign minister, and an evening conversation became an official invitation. The film was also a product of family friends, but the Sterns insisted it be about China, not them. 'Even when I see it today, that's what impresses me; it was so unpretentious,' says David Stern, whose clear admiration for his father still resonates. 'It wasn't a grand master delivering the word. My father had lived a life that very few people can live, and all he wanted to do was share it.'

Wang is certain that Stern brought about a seismic change in China's music scene. 'He showed us, he told us, he demanded from us that music was all about expressing yourself,' he says. 'The content is more important than the presentation - and in those days in China, presentation was everything.' China had talented teachers, he recalls, but the general trend was to study the form and imitate the West. 'We did not have the confidence nor the tradition to say that music is only a tool to express yourself,' he recalls. 'Isaac Stern said "I don't care how you play, but you have to say something."'

Maybe even more than music, Stern was known for mentorship, which is why the family eventually allowed his name to be attached to Shanghai's newest competition. But they had concerns. 'This was not an easy birth because my father principally believed that music is not a competition,' says David Stern. In fact, Isaac had avoided the competition circuit and nurtured talent so that others could do the same. But times have changed. 'An Isaac Stern of today would not have the influence he did then; the music world was smaller, moved slower, had more patience,' he says. 'Today it is increasingly difficult for young musicians to get their chance.'

Launched by the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra (SSO) to discover talent and honour Stern's legacy in China, the SISIVC has been designed with Stern in mind. This means that, although virtuosity is rewarded, musicianship and development will come first. David Stern himself insisted on a chamber music round, and organisers will introduce the most promising candidates to top music agencies. The jurors' scores and comments will be released to the public, so that candidates can receive further feedback. And the SSO and principal sponsor China Pacific Insurance's musical outreach programme 'The Rhythm of Life' will allow competition laureates to give concerts with the orchestra at venues across the country. 'The programme is entrusting young musicians with enriching the life and culture of urban centres around the country,' says SO president and SISIVC executive president Fedina Zhou, 'fulfilling its core philosophy of bringing music to the ears of many, and turning "soloists" into "musicians".'

Tsu, who serves with Stern as jury co-chair, feels that Shanghai - and indeed China - is due for an international competition of this scope, and is already excited about the contestants' high level. Wang feels there is no better homage to Stern. 'He cultivated and propelled so many new careers; some of the greatest performers alive are performing because of him. There are only one or two in the history of music like that. We need to keep his legacy alive.' Li also sees overwhelming positives, and points out that when it comes to music in China, SSO music director Long Yu has the Midas touch. 'Everything he organises blossoms so much,' he says. 'With anyone else I would be sceptical, but with him I have confidence that this will be great.' He also says that while many competition winners disappear after a handful of concerts,' Yu's myriad orchestra connections will be a boon for the winners. 'This will build a concrete career for these young soloists.'

But the most important factor is to keep Isaac Stern's legacy, and the From Mao to Mozart spirits alive. 'My father was one of the few who managed to elevate everyone around him,' says David Stern, 'whether it was a conversation in a restaurant or playing a violin concerto.' And this will indeed be a family affair. The violinist's daughter Shira will be presenting the Isaac Stern Award, granted to the person in any field, from any country, who best uses music to improve society. His son, conductor Michael Stern, will conduct the orchestra for the final round, before working with Yo-Yo Ma on a 2017 youth festival in Guangzhou. David Stern has been conducting in China several times a year since 1999, when he led his father and other film alumni (including Wang and Tsu) in a 20th-anniversary From Mao to Mozart concert. Today he runs an annual Baroque festival in Shanghai and teaches vocal masterclasses. He repeatedly insists he is not following in his father's footsteps, saying, 'I just believe in it and I love doing it.'

But perhaps the best takeaway is Isaac Stern's address at the end of the film: 'If you do not think that music can say more than words, that there can be no life without music; if you do not believe these things, then don't be a musician.' Says David Stern of his father's advice. 'It's the strongest defence of arts I've ever heard.' Words to live by indeed.

New York Classical Review: Long Yu Leads New York Philharmonic in Chinese New Year Program

The Philharmonic played brilliantly, sounding secure and powerful under Long Yu’s baton, and the performance of the solo part by the Philharmonic’s principal harpist, Nancy Allen, was exquisite.

Photo: Chris Lee

New York Classical Review

By Eric C. Simpson

The New York Philharmonic’s fifth annual Chinese New Year celebration on Tuesday night was something of a riddle. On the one hand, there was a ninety-minute program with a sought-after violinist, a stage address from United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, and no intermission suggested an emphasis on providing entertainment for the gala patrons whose tables were being set on the promenade outside the hall.

On the other, the most substantial item on the program by far was the New York premiere of a forty-minute piece from the last decade that proved as artistically and intellectually stimulating as anything the Philharmonic might present on a regular subscription concert.

The first music of the evening was certainly more in the former spirit, like any good concert overture: Li Huanzhi’s Spring Festival Overture, composed in 1955-56, is a peculiar product of the early years of Western-style composing in China. Li’s darting melodies and galloping energy, combined with a Romantic idiom, almost conjure reminiscences of something between the American West and a Parisian Can-can. Under the direction of guest conductor Long Yu, the music was dignified, but not humorless.

More substantial, though opaque in its own way, was the famous The Butterfly Lovers, a violin concerto written jointly by Chen Gang and He Zhanhao just a few years after the Spring Festival Overture. The soloist on this occasion was Maxim Vengerov, who a decade ago was at the top of an intensely competitive field before an injury forced his career into hiatus. Technical problems, such as murky passagework and wandering intonation, linger, but the most attractive elements of Vengerov’s playing are the ones that always stood out: the effortless warmth of his tone and keen expression of his interpretation.

The Butterfly Lovers offered the violinist ample opportunity to demonstrate these two qualities. The concerto has its stretches of showy virtuosity, but at its core it is an innocently lyrical piece, lightly orchestrated and unassuming, its solo part taking inspiration from traditional Chinese instruments rather than Romantic violinistic flair. Vengerov’s interpretation was poignant, finding moments of intense passion in the gleaming lines without ever hurrying them

Less successful was Vengerov’s performance of the Kreisler chestnut Tambourin Chinois, a fleeting bonbon that served essentially as a programmed encore. A master of pastiche, Kreisler in this brief showpiece combines Chinese musical idiom with violinistic fireworks of considerable difficulty—too much difficulty, apparently, for Vengerov, who rushed through the piece and failed to convey much its charm.

After the relative pleasantness of the first forty minutes, hearing Tan Dun’s The Secret Voices of Women was like stepping into an ice bath. Though the composer calls the piece a “Symphony for 13 Microfilms, Harp, and Orchestra,” there are no microfilm readers called for in the score; rather, “microfilm” is his name for a series of short films he has captured and edited of women in rural China singing traditional Nu Shu songs, cataloguing folk melodies in danger of being lost. Around these, Tan Dun constructs what is essentially a harp concerto, drawing inspiration from the songs and echoing them in his writing for orchestra and soloist.

At times, the writing takes the form of a simple and comfortably harmonious accompaniment, whether in the form of light pizzicato and percussion or burnished strings. At others, the echoed vocal melody becomes a maddening refrain, dissolving into interludes of shivering ice or harrowing fury.

The video scenes themselves are emotionally affecting, portraying mostly elderly women in a variety of activities, projected in three different frames above the stage. One in particular shows a song of ritual mourning, accompanied by frantic worrying in the solo harp. The songs are presented without any English text, a choice that avoids distracting from either the images or the music. One feels that Tan Dun made the correct decision here, though undoubtedly many audience members missed a layer of the work as a result.

The Philharmonic played brilliantly, sounding secure and powerful under Long Yu’s baton, and the performance of the solo part by the Philharmonic’s principal harpist, Nancy Allen, was exquisite. Tan Dun’s writing for harp is extremely demanding, not just in degree of difficulty, but in its length and relative continuity. More than equal to the technical challenges, Allen brought a strong voice to the varied solo line. Would that every gala concert left so strong an impression.

South China Morning Post: Chinese conductor Long Yu to get top honour for bridging East-West gap

Maestro Yu who recently set up Shanghai Orchestra Academy to receive prestigious prize from Atlantic Council next week alongside Henry Kissinger, Mario Draghi and Colombia's president.

South China Morning Post

By Kevin Kwong

Maestro Yu who recently set up Shanghai Orchestra Academy to receive prestigious prize from Atlantic Council next week alongside Henry Kissinger, Mario Draghi and Colombia's president.

Chinese conductor Yu Long is to receive the prestigious Global Citizen Award in New York on October 1. Yu, who is principal guest conductor with the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra, will be honoured alongside veteran US statesman Henry Kissinger for his contributions to bridging the East-West gap through classical music.

“In 2008, for the first time in history, the China Philharmonic Orchestra performed under the baton of Maestro Yu Long at the Vatican in the Paul VI Auditorium. The concert was attended by Pope Benedict XIV and marked a giant step in bringing Eastern and Western cultures closer together,” says the Atlantic Council, a US think tank on international affairs, which gives out the annual awards.

Born into a musical family in Shanghai, Yu, 51, received his early musical education from his grandfather and composer Ding Shande and went on to study at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music and the Hochschule der Kunst in Berlin. A musician with vision as well as a strong network around the world, Yu wears many hats and is the artistic director of the Beijing Music Festival and the China Philharmonic Orchestra, music director of the Shanghai and Guangzhou symphony orchestras, and the co-director of the MISA Shanghai Summer Festival.

Recognising the need for specialised orchestral training in China, Yu founded the Shanghai Orchestra Academy in September 2014 to offer a focus on ensemble work in Chinese musical education and training. The academy offers a number of courses that give students a chance to work with overseas orchestras such as the New York Philharmonic, Sydney Symphony Orchestra and North German Radio Symphony Orchestra. This collaboration further cements relationships between aspiring young Chinese musicians and their counterparts in the West.

"I can't say enough about our partners in the Shanghai team. Yu Long had a vision. [He is] incredible, amazing to work with,” Matthew Van Besien, president of the New York Philharmonic, said earlier this year.

Also being honoured at the event will be Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank, and Juan Manuel Santos, president of Colombia. Past Global Citizen awardees include actor Robert De Niro, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto and the first prime minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, who died in March 2015.

SSO to Mark Anniversaries in Performance at the UN General Assembly

For the UN concert on August 28, artists from all the major Allied powers of WW2 will be represented, performing music by Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, John Williams and a new work by Zou Ye

In one of the largest concerts ever held at the General Assembly of the United Nations, August 28 will see Maestro Long Yu assemble his Shanghai Symphony Orchestra to represent China in a musical celebration to mark 70 years since both the ending of World War Two and the establishment of the UN itself. All of the chief Allied WW2 powers will be represented in the concert, which also will include America's MasterVoices choir (formerly the Collegiate Chorale, the choir which performed at the official opening of the UN building), Russian-born violinist Maxim Vengerov (playing Schindler's List), 12-year-old Chinese piano prodigy Sirena Wang, and singers Ying Huang (China), Sarah Fox (UK), Aurhelia Varak (France), Vadim Gan (Russia), David Blalock (USA) and Christopher Magiera (USA). The concert is part of a tour of the Americas by the orchestra, and will also take in two venues in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Aug 30, 31), and one in Buenos Aires, Argentina (Sept 2).

"It is a concert in which the music we play is about memories and about new beginnings" says Long Yu, "World War Two was of course a great tragedy, as well as a victory over evil, which must be remembered, while the birth of the UN from out of the wreckage of that war was a new beginning for the world. So Tchaikovsky's Andante Cantabile is contemplative, healing, Barber's Adagio is a piece of hushed mourning, as of course is John Williams's Theme from Schindler's List. Then Beethoven's Choral Fantasy is a work of genesis, one that eventually culminated in the magnificent Ninth Symphony and its 'Ode To Joy' - but in this exuberant early work we can hear the seeds of that utopian vision, which is very appropriate for a forum created around the ideal of nations talking and collaborating, rather than fighting." The new work, Shanghai 1937, is by the Chinese composer Zou Ye (Long Yu recently initiated the Compose 20:20 project, to bring new Western works to China, and new Chinese works to the West).

Nor does the sense of history that attends this event elude its conductor. "Speaking for myself and the players as well as the management of the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, to be able to represent our country in the spirit of the great things achieved by the allies and the founders of the United Nations seven decades ago, is an immense privilege. To be part of a cultural message from artists of China, the US, UK, France and Russia that we hope represents the renewal of those ideals is an honor to be cherished. And it also feels appropriate that this concert is part of our wider tour of the Americas - as much as we are bringing in artists from different nationalities to our concert halls, we musicians are also ourselves physically travelling from country to country, to help strengthen the bonds that bind nations, and people, together."

The orchestra will also be joined by nine students from the Shanghai Orchestra Academy, an initiative created with international cooperation with the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

Notes for Editors:

* The Shanghai Symphony Orchestra is China's oldest symphony orchestra, founded in 1879 as the Shanghai Public Band (under conductor and flautist Jean Remusat). Between these years and the end of World War Two, some European musicians came to the orchestra as section leaders, bringing with them their knowledge of European performance styles - after World War Two, however, the Europeans gradually left creating opportunities for the most talented Chinese musicians. In 1956 the orchestra, already informally known as "the best in the Far East", renamed itself the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra. Xieyang Chen took over the artistic leadership, creating and filling the role of music director. He was succeeded by the current incumbent, Long Yu.

The SSO has performed around the world. It was the first Chinese orchestra to play Carnegie Hall, in 1990, the first to play the Berlin Philharmonie (2004), the first to give a concert in New York's Central Park (2010). Last year, it inaugurated its new, world-class concert venue in Shanghai, Symphony Hall, ingeniously built underground for urban planning reasons. And it also recently created a major new popular classical music festival - MISA (Music in the Summer Air) - with joint artistic directors Long Yu and Charles Dutoit.

In 2014 the SSO and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra launched the NYPO's Shanghai Orchestra Academy and Residency Partnership, a joint endeavour of both orchestras that included the founding of the Shanghai Orchestra Academy (SOA) which opened in September 2014, and the NYPO's four-year performance residency in Shanghai.

* Maestro Long Yu is Music Director of the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, also of the Guanzhou Symphony Orchestra, the Artistic Director and co-founder of the China Philharmonic Orchestra, and Principal Guest Conductor of the Hong Kong Philharmonic. He is also Founding Artistic Director of the Beijing Music Festival, co-founder of the Shanghai MISA Festival and incoming Principal Guest Conductor of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra.

He helped spearhead the establishment of the New York Philharmonic's Shanghai Orchestra Academy and Residency Partnership (see above) and is an honorary member of the International Advisory Board of the New York Philharmonic. Other China ‘firsts’ include bringing the first-ever performances of Wagner’s Ring cycle in the country, presenting its first-ever Mahler cycle, releasing the first album of Chinese music on a major recording label (Dragon Songs, alongside Lang Lang, for DG), and bringing the first-ever Chinese orchestra to play at the Vatican. Last year, he led the China Philharmonic as the first Chinese orchestra ever invited to play at the BBC Proms. The Shanghai Symphony under his baton was the first orchestra other than the New York Philharmonic to perform on Central Park's Great Lawn.

He has commissioned new works from many of today’s leading composers, among them Tan Dun, Krzysztof Penderecki, Philip Glass, John Corigliano, Guo Wenjing and Ye Xiaogang and has created a five-year initiative, Compose 20:20, to bring new Chinese works to the West and new Western works to China.

He was recently awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur from the French governnment, only the third Chinese national ever to receive it. This award marked a highlight of an impressive 2014 season for Maestro Long Yu. Last July, starry concerts in Shanghai and Beijing coincided with his 50th birthday, and colleagues including Lang Lang, Alison Balsom and Maxim Vengerov performed, with new works composed by Tan Dun, Qigang Chen and John Williams. At the same time, he led the Shanghai Symphony into their new home, a state-of-the-art venue built mostly underground, acoustically designed by Yasuhisa Toyota.

Long Yu regularly conducts important orchestras and opera houses in the West such as the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Orchestre de Paris, Chicago Symphony, BBC Symphony, Teatro La Fenice, Hamburg Staatsoper and Philadelphia Orchestra. He was previously honored to be appointed a Chavelier dans L’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France, and a L’onorificenza di commendatore from the Republic of Italy.

In August 2015 he led the China Philharmonic on a tour of the old Silk Road trade route, taking in coutries such as Athens, Turkey and Iran - making China the first of the P5+1 negotiating partners to send an orchestra to Tehran following the much-discussed nuclear agreement (they played Dvorak's New World Symphony, among other repertoire).