Los Angeles Times: Kanye meets Beethoven: How young musicians are mixing classical with pop

It wasn't quite Little Coachella in Little Tokyo. But as if out of nowhere, more than 1,000 hip-hop fans, some wearing Kanye West T-shirts, descended on the Aratani Theatre. A few had arrived as early as noon on Saturday and waited in the hot sun for a 7:30 p.m. concert.

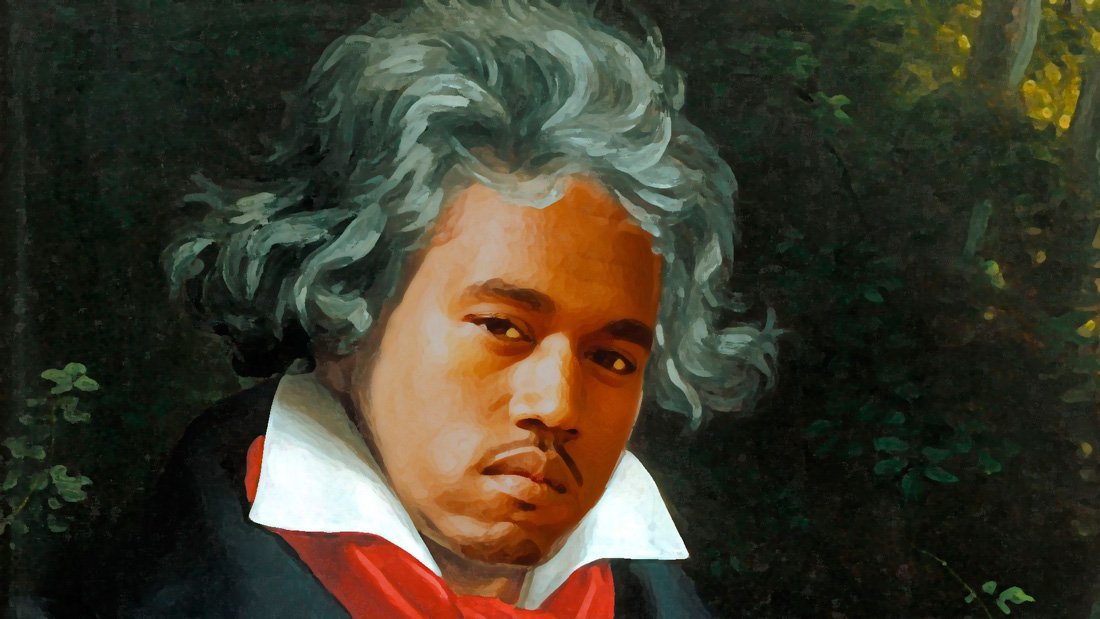

Photo: Kanye: Flickr/David Shankbone. Beethoven: Shutterstock

The Los Angeles Times

By Mark Swed

It wasn't quite Little Coachella in Little Tokyo. But as if out of nowhere, more than 1,000 hip-hop fans, some wearing Kanye West T-shirts, descended on the Aratani Theatre. A few had arrived as early as noon on Saturday and waited in the hot sun for a 7:30 p.m. concert.

Once the crowd had taken over San Pedro Street, the police came by to see what was going on. It was no big deal, they were assured, simply a queue for free tickets to the Young Musicians Foundation Debut Orchestra's Beethoven concert.

Make that Yeethoven, short for "Yeezus" (West's 2013 album) and Beethoven.

Meanwhile, not far away in Glendale, the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra sandwiched between the tame "Classical Symphony" of Prokofiev and "Clock" Symphony of Haydn a new cello concerto by Mason Bates, who has one foot in electronica and moonlights as a DJ.

Is something going on? Yes and no.

Every generation genre-bends, each in its own way. They always have and, no doubt, always will. Eyebrows go up and they go back down. But by now it has gotten pretty hard to shock.

What does seem new is the lack of controversy. One almost longs for the days when Parisians rioted the premiere of Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring," the Viennese practically threw Mahler out of town for smudging the sacred symphonic art form with street music, and the 1950s avant-garde horrified the establishment with pursuits that redefined the definition of music.

I heard the Sunday night repeat of LACO's program at UCLA, and for both this and the YMF event Saturday, the musical and social welcoming mat easily co-opted rebellion. Still, it is hard to complain about attaining, through music, a unifying feel-good mood in our otherwise divisive feel-bad times. "Yeezy season approachin'," West tells us. Could that be the revolution we need?

What made "Yeethoven" especially engaging was its unmistakably sincere musical roots. The Debut Orchestra, a training ensemble for instrumentalists and conductors founded in 1955, happens to boast among its alumni André Previn and Michael Tilson Thomas, famed for their groundbreaking mixing of symphonic and pop worlds. The 26-year-old Juilliard-trained YMF music director Yuga Cohler is in their mold, a self-proclaimed hip-hop fan since childhood who does not see that and Beethoven as worlds in opposition.

A young composer of like mind, Stephen Feigenbaum, served as "Yeethoven" arranger and co-curator. Six Beethoven scores were paired with songs from "Yeezus," each grouping given a theme — Form, Contrast, Harmony, Rhythm, Gesture and Will — representing qualities Cohler and Feigenbaum find shared across centuries and cultures by Beethoven and West.

Introducing the pairings, Feigenbaum noted the chaotic, over-the-top nature of Beethoven's "Egmont" Overture and West's "New Slaves" or the heroic yet ambiguous character of the snappy second movement of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony and "Hold My Liquor." These are, of course, all general enough qualities that you could make the same case for any number of composers.

In fact, dissimilarities could be more striking than similarities, beginning with an informal pop crowd that little resembled the formal musicians on stage. Neither do Beethoven and West sound alike. And while West does profess some of Beethoven's democratic ideals and confidence, there are also major differences, such as the pop star's attitude toward women so radically opposed to Beethoven's idealized "Immortal Beloved." And, of course, orchestra and pop concert settings have little in common.

Yet "Egmont" and "New Slaves" are, each in its own way, transgressive arguments for freedom. Putting West in orchestral dress and removing the vocals meant avoiding anything offensive. Were his language to be used in a traditional classical concert (or this newspaper, for that matter), there really would be trouble.

All but two of the pairs were mash-ups. Beethoven seldom upgraded West, rather West infected Beethoven with contemporary funk and spunk. The final mash-up mattered most. An orchestral arrangement of the last movement of the Opus 131 string quartet undercut Beethoven at his most spiritually transformative with the raunchy side of West in "On Sight." Cohler and Feigenbaum's theme was Will, but it could just as easily have been Impurity. Beethoven kept earthy, and West's music rose spiritually higher than you might have otherwise expected.

For the enthusiastic crowd (200 or more were turned away), every recognizable West hook got a shout out and Beethoven got respect. Cohler conducted with surety and security. The orchestra, though looking a little dazed in these surroundings, played with a joyful sense of making a history.

The crowd at Royce Hall on Sunday night was more standard issue for LACO, with but a few more young people than normal in attendance. (I wonder what would happen with audiences at UCLA if the school eliminated its $12 parking fee for concerts.) Much of the interest here focused on Matthew Halls, the British conductor who became music director of the Oregon Bach Festival two years ago and whose strong showing makes him a credible candidate in LACO's music director search.

An all-around early music guy whose recording of Bach harpsichord suites is a knockout, Halls also happens to be big on 19th century opera, symphonic blockbusters and contemporary music. He went for boldness in both Prokofiev and Haydn, getting some of the loudest playing I've heard from the orchestra.

But he put most of his attention on Bates' new Cello Concerto, which had its premiere earlier this year with the Seattle Symphony (conducted by Mirga Grazinyte-Tyla). It was written for Joshua Roman, who has his own street cred. The popular young cellist will, for instance, be playing at Amoeba Music on Wednesday, and he showed up at Royce in a showy print suit reminiscent of '60s Carnaby Street.

Bates is everywhere. The new composer-in-residence of the Kennedy Center (a first), he will have his next premiere streamed next week on the San Francisco Symphony Facebook page (believed to be a first for a major orchestra). He has lively orchestral imagination excellent for evoking specific sonic environments (such as primordial life or a future colony in Iceland) by adding beats and electronica effects to snappy melodies.

The Cello Concerto is more traditional. It includes instances of lightweight jazziness and commercial pop. It exploits Roman's flowery virtuosity and offers the cellist diverting light touches — such as bouncing the bow on the strings and plucking them with a guitar pick. But with Roman's propensity for cuteness, this concerto becomes less the transgressive expansion of our musical vocabulary than a contrivance suitable for taming the "monster about to come alive again" that West unleashes in "Yeezus" and Cohler cavorts with in "Yeethoven."

Washington Post: Anne Akiko Meyers: Violinist breaks a leg — or rather, a foot.

“Break a leg” and “the show must go on” are among the most overused injunctions in the performing arts. On Friday, Anne Akiko Meyers joined the lists of performers who have obeyed both.

The Washington Post

By Anne Midgette

“Break a leg” and “the show must go on” are among the most overused injunctions in the performing arts. On Friday, Anne Akiko Meyers joined the lists of performers who have obeyed both.

To be exact, she didn’t break a leg. She broke her foot. But it didn’t stop her from performing Mason Bates’s challenging violin concerto with the National Symphony Orchestra on Friday and Saturday nights (after Thursday night’s unhampered performance).

“I thought I just completely sprained my foot,” the violinist said by phone from her home in Austin, Texas on Monday afternoon. “It was black and blue. But I didn’t know it was broken. I have never broken anything in my body.”

On Friday night, all that was evident was a slight limp – and slightly unconventional footwear, sturdy platform sandals. (“They’re like wearing sneakers,” Meyers said.) Sitting in the audience, I might not have noticed either had I not been tipped, off the record, before the concert, that Meyers had had a bad fall in the afternoon. That explained the placement of a stool on stage; but in the event, Meyers walked out, did not use the stool, and played the difficult concerto with aplomb.

By Saturday morning, the foot had ballooned. For Saturday night’s performance, Meyers used a wheelchair to get on stage – but still played standing up.

“You cannot sit and play Mason’s music,” she said on Monday. “It doesn’t work.” Besides, she added, “If I had sat, I would never have gotten up.”

The accident itself was relatively benign, or perhaps “domestic” is a better term: Meyers was pushing a stroller with her two daughters, ages four and five, while checking her e-mail on a smartphone, and didn’t see the curb at the edge of the sidewalk.

“It happened at like two o’clock,” she said. “I had a soundcheck at four.” There wasn’t time to go to the doctor, and besides, she was pretty sure what a doctor would say: “You need to ice it, and elevate, and medicate: three things I couldn’t do at that moment.”

It wasn’t until she got home to Austin on Sunday that she went to the emergency room and discovered that she had played with a broken foot.

Her misadventure is reminiscent of the time in 2009 that the mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato fell on stage and broke her leg during a performance of “The Barber of Seville” at Covent Garden. DiDonato finished the performance, on crutches, and then went to the hospital. She sang the next performance in a wheelchair.

But opera staging involves so much physical activity that people are apt to get hurt once in a while. (I remember a night when the stage knife failed to retract when Don Jose stabbed Carmen, drawing blood from the mezzo-soprano Elena Zaremba. Fortunately he only hit her arm.) Generally speaking, the concert stage tends to be a less perilous place.

Meyers is not cancelling any performances. Next on her schedule is a recording in London of a new piece by the Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara, Szymanowski’s violin concerto, and Mortin Lauridsen’s arrangement of his popular “O Magnum Mysterium.” At least no one will see her footwear for that.

Huffington Post: Yeethoven Is The Kanye And Beethoven Mashup You’ve Been Waiting For

The Young Musicians Foundation Debut Orchestra, led by conductor Yuga Cohler and composer Stephen Feigenbaum, is bringing hip-hop and classical music together.

Photo: Priscilla Frank

The Huffington Post

By Priscilla Frank

The Young Musicians Foundation Debut Orchestra, led by conductor Yuga Cohler and composer Stephen Feigenbaum, is bringing hip-hop and classical music together.

When Kanye West released his sixth solo album, titled “Yeezus,” in 2013, he —with a single turn of phrase — fused his identity with that of the central figure of Christianity. The connection between Ye and JC was more than just an egotistical outburst from a narcissistic rock star, but a message about power, sacrifice, influence and vision, albeit a bombastic one.

Now, three years later, Ye has received another rather complimentary comparison. On April 16, at the Artani Theater in Los Angeles, the Young Musicians Foundation Debut Orchestra will perform “The Great Music Series: Yeethoven,” comparing Mr. West to Ludwig van Beethoven, and thus exploring the overlap between classical and hip-hop, 18th-century poofy collared shirts and 2013-era leather pants.

Yuga Cohler is directing the performance, along with project co-creator and composer Stephen Feigenbaum. The two, natives to the classical music world and longtime fans of Kanye’s work, have played music together since high school.

The Young Musicians Foundation Debut Orchestra is made up of 70 Los Angeles-based musicians between 15 and 25 years old. Cohler was appointed director last year. “I knew one of the things I wanted to do was make classical music engage with music of today, music that is very widely heard and massively popular,” Cohler explained to The Huffington Post.

From the beginning, Cohler and Feigenbaum were interested in “Yeezus,” the dark, grating, vinegary album that at once feels like a protest, a divine revelation, a nightmare and an industrial rave. “There are a lot of things in the album more reminiscent of classical than pop or hip-hop,” Feigenbaum said. “We tried to examine that and make that case that the commonalities across genres are more interesting than genre barriers.”

With “Yeezus” as a starting point, Cohler and Feigenbaum set out to find an unlikely musician whose sound reverberated with Ye’s. And if said musician happened to have an extremely punnable name, so be it. “We quickly came to Beethoven as someone similarly controversial in his time, someone brash and aggressive,” Cohler said. “Beethoven was rough around the edges. He’s one of the earliest examples of modernity, and often the audience really didn’t like it.”

They then began matching up Yeezus songs with analogous pieces from Beethoven’s oeuvre. For example, Kanye’s “New Slaves,” an epic harangue encompassing everything from systemic racism to fashion addiction, showed similarities to “Egmont Overture” in its dark, tumultuous energy. “In both songs, the endings are bizarrely uplifting, it almost feels bitter,” Cohler explained.

At first, the concert will juxtapose songs by Kanye and Beethoven to illuminate the comparisons aligning them. As the concert continues, the artists’ work will become ever more integrated, until the line between them becomes jagged and molten. “I think the boundaries we set up [in music] are necessarily artificial and don’t need to be adhered to,” Cohler said. Feigenbaum added: “We’re interested in getting out of the box that classical music puts us in.”

Although Cohler and Feigenbaum stress that their project is less concerned with the personas of the artists at play, and more concerned with their work, it’s hard to ignore the fact that, like Kanye, Beethoven was also something of an egoist. When a review of his “String Quartet No. 13” declared the work “incomprehensible, like Chinese,” he responded indignantly and without a hint of self-doubt, calling his audience “Cattle! Asses!” One of his most iconic quotes, “There are many princes and there will continue to be thousands more, but there is only one Beethoven,” sounds similarly familiar.

The show concludes with a comparison of the last movement of Beethoven’s “String Quartet No. 14” and Kanye’s “On Sight,” which opens his album. “If you don’t know the pieces you would have no idea where one piece starts and the other ends,” Cohler described. “It’s so emblematic of the artistic embryo that characterizes both Beethoven and Kanye — that propulsion, impulse and drive.”

Not everyone is psyched about the performance. Pitchfork Senior Editor Jayson Greene called the project “spectacularly ill-conceived.” Greene, who writes about both classical and hip-hop music, sees little connection between the two artists beyond a catchy conjoined nickname, and described the effort as a lazy attempt to bridge high and low culture that underestimates both artists and their audience.

“Lumping things on two sides of a room and drawing a line is less difficult than figuring out where each individual element belongs in a space,” Greene wrote. “And if you are going to start mixing and matching — say, by establishing a parallel between a rapper and a composer that leaps over genre boundaries, countries, and hundreds of years — for god’s sake, think hard about what you’re doing.”

Whether or not you like the resulting Yeethoven mashup, after speaking with briefly with both Cohler and Feigenbaum, it’s difficult to deny that they’ve put quite a lot thought into the pairing. This concert has been in preparation for about a year. And while Greene posits Igor Stravinsky as a stronger parallel to West, his argument is based as much upon the artists’ characters and visions as the actual content, which Cohler and Feigenbaum privilege.

As someone who knows far less about classical music, I cannot confidently comment on the solidity of the parallel between Ye and Be, at least not until the show takes place on April 16. However, I fully support the mission of a free, instructive concert performed by an orchestra of young people, illuminating bridges between unlikely artists that can be embraced or rejected by the audience as they see fit.

Rather than insulting their audience, Cohler and Feigenbaum invite people to participate in an imperfect experiment, one that can illuminate the tenuous nature of boundaries and categories confining all art forms. “The more young musicians that realize they can learn Bach and also improvise and play in a band and [learn that] those don’t have to be totally separate,” well, these are all good things, right?

Besides, the potential for “Yeethoven” to result in outrage, disagreement, slippage, disharmony and even misguided overconfidence sans apologies seems quite appropriate for the subject matter, no?

“The Great Music Series: Yeethoven“ takes place Saturday, April 16, at 7:30 p.m. The event is free, but tickets are required, available first-come first-serve starting at 6:00 p.m.

DC Metro Theater Arts: Pianist Bruce Levingston Presents ‘Creating An American Citizen’ at Georgetown University

On Wednesday, April 6, 2016, a captive audience was treated to a performance by acclaimed pianist Bruce Levingston, in Georgetown’s stunning Gaston Hall, the setting sun streaming through the stained glass windows. Without bravado, Levingston has a powerful stage presence that never distracts from the music. Some artists seem to demand their audience’s attention with frenetic energy. But it takes a special artist like Levingston to invite his audience on a journey – in which one’s attention is given freely. He has a special ability to captivate not only the ears of his audience, but their hearts as well.

Pianist and author Bruce Levingston in front of Marie Hull’s ‘Pink Lady.’ Photo: Rick Guy

On Wednesday, April 6, 2016, a captive audience was treated to a performance by acclaimed pianist Bruce Levingston, in Georgetown’s stunning Gaston Hall, the setting sun streaming through the stained glass windows.

Levingston, a Mississippi native, exudes southern charm. An elegant performer, he was passionate and intense in an unobtrusive way. Without bravado, Levingston has a powerful stage presence that never distracts from the music. Some artists seem to demand their audience’s attention with frenetic energy. But it takes a special artist like Levingston to invite his audience on a journey – in which one’s attention is given freely. He has a special ability to captivate not only the ears of his audience, but their hearts as well.

After each piece Levingston would stand for our thundering applause and give us a friendly smile, a humble bow of his head, and sometimes a bashful shrug. His programming and selections are tailored perfectly for him; I couldn’t see any other artist performing the pieces quite as well, with the same power, yet sensitivity.

As discussed recently in a moving and informative DCMetro TheaterArts interview, Levingston was invited to Georgetown University to present the DC Premiere of An American Citizen, commissioned by Composer Nolan Gasser, inventor of the Musical Genome Project. The piece pairs the musical composition with a film directed by Jarred Alterman who used works from Mississippian Artist Marie Hull to tell a series of stories and explore issues the politics of race.

Levingston is also the Founder and Artistic Director of the music foundation Premiere Commission, Inc., which has commissioned and premiered over 50 new works, and celebrated its 15th anniversary this year.

Levingston started the program with two contrasting pieces by Philip Glass; “Etude No. 2” and “Etude No. 6”. “Etude No. 2” was a magical and flowing piece, with rolling chords and deep bass notes. It moved along as if cresting on waves, getting more and more intense and then pulling back. With a sensitive touch, the music seemed to flow through Levingston.

He moved directly into “Etude No. 6” which started on a fast clip. It was high in emotional intensity with a more pronounced melody in comparison to the bass heavy “Etude No. 2.” Levingston’s dynamic variations and increasing tempo towards the end of the piece left me breathless.

Levingston took time to share the story behind his third selection, A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close II. Chuck Close, a famous artist, suffered from paralysis after a sudden rupture of a spinal artery after which time he learned to paint with a brush between his lips. Eventually he gained movement of his arms and began to paint more freely again. Close later painted a portrait of his long-time friend, composer Philip Glass.

Levingston had an opportunity to meet with Glass at an exhibition of Close’s works and asked if Glass would consider making a “portrait” of Chuck Close, using sound. Glass replied “If you’ll play it, I’ll write it.” A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close II was just as Levingston described it would be: soaring – bittersweet, yet triumphant. It evoked the sentiments of a personal struggle. It quickly shifted moods throughout, yet it all tied together.

A Philip Glass novice, I felt immediately grateful for the exposure to these three pieces. A lover of Bach and Mozart, the works of Glass added something dramatic and enriching to my usual listening experience. The pieces had all of the finesse and structure of Mozart with the added romance of later composers. I felt that I was taken on a journey – the pieces were evocative without taking a heavy emotional toll.

Levingston then enchanted the audience with Frederic Chopin’s “Nocturne in B-flat minor, Op. 9, No. 1.” Played with beauty, I found myself holding my breath, wanting to be held in time so the transcendent experience would not stop.

Finally, we heard the DC Premiere of Nolan Gasser’s An American Citizen, based on the famous 1936 painting of the same name by Marie Hull, which depicts Mississippian John Wesley Washington, a man born into slavery, as well as a number of Hull’s other subjects.

The accompanying film by Jarred Alterman was perfectly paced to the composition, contrasting between portraits and landscapes, darker parts of the music highlighting the intensity in the eyes of one sharecropper, and lightening up when falling upon the dancing eyes of John Wesley Washington; sharpening when focused on the gnarled hands of one man, and then mellowing as the film zoomed in on a landscape. Alterman took his time with the frames and the pacing, making creative choices with zooming, focus, and lens movement. The combination of film and music made the experience truly unique and I find it difficult to imagine the composition having the same emotional impact on the viewer without the accompanying film.

Georgetown University President John J. DeGioia joined Levingston onstage to discuss An American Citizen, as well as art, race, politics, and the artist Marie Hull. He asked exciting questions about Levingston’s knowledge of Marie Hull and her portrait subjects. For instance, Levingston shared that one portrait subject highlighted in An American Citizen has a living daughter in her 90’s, named Eva, with a fantastic memory.

Levingston arranged for her family to see the actual portrait of her father, a sharecropper. Eva took art lessons from Marie Hull, and recalled that her father was proud and didn’t want to be called a sharecropper, yet Marie Hull asked him to put on overalls and play the part for the portrait; she was trying to capture something. The subject asked if Marie Hull would give his daughter art lessons in return for sitting for the portrait. He wanted better for his family; there was humanity in these subjects. Levinston believes that Marie Hull’s story is important for people to hear and this led him to write a stunning biography about the artist – Bright Fields: The Mastery of Marie Hull.

President DeGioia opened the floor for questions. Elizabeth Baker, Georgetown Senior and classical musician, asked for suggestions on bridging the generational gap and bringing classical music to younger generations. Levingston mused that if Mozart lived in this era, he would be a great film composer because it is the medium of our time. He went on to say that "Music is a visual thing now, particularly with social media and YouTube – take advantage of what is great in our era and sense what is coming next – be daring and take some chances – package it in a way to reach everyone."

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Brevard, a Georgetown graduate (2014) from Mississippi, made a final comment that really got to the heart and soul of the evening. Having watched the film, listened to the music, studied Marie Hull’s art, Brevard was moved by the dignity within the subjects, saying, "What an incredibly poignant experience that these individuals, who very likely had limited education, are being given a voice…their story is being heard in 2016 at Georgetown University in Gaston Hall."

With misty eyes, Levingston strode across the stage to give Lizzie a warm embrace.

Haley Reeves Barbour, the 62nd Governor of Mississippi, (2004-2012), was also in attendance and finished by saying that Mississippi is very proud of Levingston.

I was indeed fortunate to go on this fascinating journey with Levingston and he has an appreciative following waiting with bated breath for his return to DC!

BBC Music Magazine: Musical Peaks in the Old West

The international renowned Grand Teton Music Festival springs up each year in one of the earth's most beautiful and awe-inspiring landscapes, as Oliver Condy discovers.

BBC Music Magazine

By Oliver Condy

Tucked into the northwest corner of Wyoming sits the majestic Teton mountain range, its peaks rising 2,000 meters either side of the vast, flat valley floor, known as Jackson Hole. In winter, the Tetons host world-class skiing, but come summer, the lush grassland, forests, lakes and rivers of Jackson Hole teem with wildlife, including eagle, elk, moose and grizzly bear, along with thousands of tourists who head there for kayaking, walking, rafting, fishing, horse riding... Jackson Hole styles itself as the 'Last of the Old West' and there are still ranches where you can see cowboys at work.

But if, like me, you don't catch so much as a whiff of a moose or bear, you can console yourself with the sight and sounds of one of America's most impressive music festivals. Located in the ski resort of Teton Village, the Grand Teton Music Festival (GTMF) is, at over 50 years old, almost as well established as the geyers in nearby Yellowstone Park. Scottish conductor Donald Runnicles, who's often seen sporting a stetson, has been the festival's music director since 2006, bringing the GTMF to a wider international audience and attracting world-class soloists and conductors. Most of the concerts take place in the 600-seat Walk Festival Hall, built in the 1970s. 'A lot of people think this is an outdoor location.' Runnicles says over a coffee at one of Jackson Hole's ranches, 'but they're astonished to find we have this jewel of a hall.'

And playing in it is a jewel of an orchesta, an unpaid, crack team of players made up of members of the finest orchestras across the US. Many of them have been coming to Jackson for over 10 years (one or two for almost 30) and most of them stay for at least two or three weeks during the summer - over the course of the festival's five weeks, hundreds of musicians pass through Jackson Hole. Simply playing for the joy, they say, is a chance for them to 'renew their vows' with orchestra music, to remind themselves why they play music, without the crushing pressures they're up against at home. 'It's not a gig,' says Utah Symphony Orchestra's Ralph Matson, festival veteran of 20 years. 'Everyone's here because they want to make music together' chips in Seattle Symphony violist Susan Gulkis Assadi, who has made Jackson Hole something of a second home during the summer. 'It's the most collegial orchestra in the world.' 'Each member of the orchestra is reminded what a privilege it is to be performing great music with great musicians,' says Runnicles. 'There are moments during performances that I'm viscerally aware of who I have in front of me.'

Runnicles faces the challenges of not only pleasing his faithful audiences but also the orchestra - feeding them repertoire that doesn't make them feel they're on a busman's holiday. 'I'm not going to attract people from Chicago, Philadelphia, Dallas or The Met if I programme Tchaik Five, Rach Two...They've done those sorts of pieces. I see the music we play as nutrition - they have to do something where they're challenged.'

2015's curveball was Vaughan Williams's Symphony No. 3, a work that most of the musicians, plus Runnicles himself, hadn't performed before. The previous year it was Vaughan Williams's Fifth Symphony, also well received. 'Every one of our players will return to their orchestras and share their new love of Vaughan Williams. So many of the musicians have come up to me and thanked me for introducing them to this music.'

Jackson Hole's elevation also presents its demands: the dryness and lack of humidity makes playing a reed instrument a lot trickier. And singers, who have to take more frequent breaths than usual during performances, are advisde to acclimatise by arriving a few days earlier. Not that they need any encouragement to spend more time in Jackson Hole...

Strings Magazine: Julian Rachlin Among 4 Soloists Who Talk About Stepping Up to the Conductor’s Podium

While conducting schools and academies still turn out the greatest number of new conductors, there is an accelerating trend among young virtuoso string players to leapfrog the traditional process on their way to the podium.

Strings Magazine

By Laurence Vittes

While doing a little research during the conducting finals of the 2015 Gstaad Menuhin Festival & Academy, I discovered a pattern. Basic training for most conductors begins at the piano. However, a number of notable string players, too, have traded in their instruments for the baton with great success. Lorin Maazel started out as a violinist; Carlo Maria Giulini, a violist; Arturo Toscanini and John Barbirolli, cellists; and Serge Koussevitzky and Zubin Mehta, double-bassists.

Violinist Itzhak Perlman took the step with some success, and violinist Joshua Bell was named music director of the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields in 2011. While conducting schools and academies still turn out the greatest number of new conductors, there is an accelerating trend among young virtuoso string players to leapfrog the traditional process on their way to the podium.

In order to find out what makes young soloists want to become conductors, I spoke to violinists Julian Rachlin and Gemma New, and cellists Eric Jacobsen and Han-Na Chang.

Julian Rachlin

As a violinist, violist, recording artist, and educator, Julian Rachlin has established close relationships with many of the world’s most prestigious conductors and orchestras. In September 2015, he took up his new position as principal guest conductor with the Royal Northern Sinfonia at the Sage Gateshead concert hall, and has been guest conducting around the world. Rachlin plays the 1704 “ex Liebig” Stradivari, on loan courtesy of the Dkfm Angelika Prokopp Privatstiftung, and a 1791 Lorenzo Storioni viola. He uses Thomastik-Infeld strings.

What inspired you to conduct?

I’m not the type who plays the Tchaikovsky and Brahms concertos, then sits down until the next time. For me, the violin is not as important as it might seem; it’s not even my favorite instrument. But whether I play violin or viola, teach, or conduct, it’s all about a life in music—being curious, and staying inspired and fresh.

What is your favorite instrument?

I always wanted to be a cellist like my father, and a recording by Rostropovich was the very first piece of music I listened to when I was two, sitting with an umbrella, which I pretended was a cello with a stick as my bow.

[Editor’s Note: According to a 2015 violinist.com interview, Rachlin was “tricked” into playing violin by his grandparents, who gave him a violin at age two and a half, and claimed it was a cello.]

What were your first experiences as a conductor?

My life as a conductor started around 2005 when I was asked by the Mahler Chamber Music, the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, and the English Chamber Orchestra to come in and play concertos without a conductor. At first, I just stood there, but when players asked me if I wanted to say something, if I had any ideas, I was surprised. Nobody had ever asked me to say anything. When I saw that the players took my ideas seriously, that they found something in what I said and what I transmitted through my body language, I began to take the idea of conducting more seriously.

How did you start developing your conducting skills?

Before I took lessons, I talked to many conductors, asking their opinion, and Zubin Mehta, Mariss Jansons, and Daniele Gatti all encouraged me. In fact, Mariss told me to take lessons from my mom—Sophie Rachlin, a graduate of the St. Petersburg Conservatory in choir conducting—together with Valery Gergiev, Semyon Bychkov, and Jansons. Of course, I didn’t want to take lessons from my mom at first, but I took one lesson and was so impressed that I’ve been studying with her now for six years.

How have you approached building repertoire as a conductor?

I’m learning one symphony a year, to make sure I will know each of them inside out. So far, my repertoire consists of Tchaikovsky 4, Beethoven 7, Mendelssohn 4, and Mozart 35, 39, and 40. My priority is still my violin, but I’m doing more and more guest conducting, including my debut at the Musikverein in Vienna, conducting Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro Overture, and Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto and Fourth Symphony.

Music Industry News Network: Festival D'Aix & Beijing Music Festival Sign Five-Year Agreement

Two of the world's most renowned music festivals have agreed an historic five-year artistic collaboration, orchestrated by the KT Wong Foundation.

Long Yu, Linda Davies, and Bernard Foccroulle in Beijing, October 2015

Music Industry News Network

Two of the world's most renowned music festivals have agreed an historic five-year artistic collaboration, orchestrated by the KT Wong Foundation.

Bernard Foccroulle, Artistic Director of the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence, and Long Yu, Founder and Artistic Director of the Beijing Music Festival, signed an agreement on 10th October 2015 that will see an exchange of the finest classical and operatic productions between China and Europe.

This groundbreaking partnership will launch in October 2016 with a series of performances of Benjamin Britten's operatic masterpiece, A Midsummer Night's Dream. This 2015 revival of the legendary 1991 production, directed by Robert Carsen, will be staged at the Poly Theatre in Beijing as part of the Beijing Music Festival.

This unique cultural milestone was conceived by the pioneering KT Wong Foundation, an organisation that has led the way in delivering boundary-pushing cultural, artistic and educational exchanges between China and the West since its launch in 2007. As well as a commitment to promoting cultural relations, the Foundation has also established itself as a leading supporter of young musical talent in China, Europe and the US.

Under the leadership of Founder and Chairman Lady Linda Wong Davies, the organisation has been a longtime supporter of both the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence and the Beijing Music Festival, and worked tirelessly over the past three years to bring them together.

In France the Foundation has supported a range of productions presented at the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence including:

- Handel's Ariodante directed by Richard Jones

- JS Bach's Trauernacht directed by Katie Mitchell

- Britten's A Midsummer Nights Dream directed by Robert Carsen

- Tchaikovsky's Iolanta/Persephone directed by Peter Sellers

- Jonathan Dove's Monster in the Maze directed by Marie-Eve Signeyrole

In addition the Foundation has been introducing the work of the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence to Chinese audiences since December 2014 with a series of film screenings in Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin of some of the Festival's previous seminal productions. These extraordinary productions have included Patrice Chéreau's chilling production of Strauss' Elektra, The Robert Carsen sparkling revival of A Midsummer Nights Dream and Robert Lepage's water-filled production of Stravinsky's The Nightingale.

Lady Linda Wong Davies said: "The KT Wong Foundation are extremely proud to have played a key role in securing this historic partnership between the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence and the Beijing Music Festival.

"These two leading music festivals are recognised for showcasing the world's finest artistic and musical talent, and this argument will allow them to reach out to new audiences in both countries, create new artistic ventures, and provide opportunities for young artists, creators and performers.

"The KTWF has worked tirelessly over the past three years to bring these two festivals together. This collaboration represents a significant triumph for the Foundation's continuing commitment to building cultural bridges and creating the best environment for artistic exchange to thrive between China and the West.

"I commend my colleagues B Foucroulle and Maestro Long Lu on their individual and combined vision and courage to come together in their desire for greater artistic creativity and excellence.

"We must remember that in these uncertain times, where our societies are rocked by economic and political changes, that France has continued to show the world that support of the cultural arts remain a priority. The leadership shown by the signing of this agreement is a testament to the strength of the relationship between France and China.'

"Since its launch in 2007, the Foundation has already produced a hugely diverse body of work, creating, producing and supporting boundary-pushing creative ventures across disciplines including opera, design, architecture and film.

"I am very excited to be part of this cultural milestone and look forward to helping make this unique collaboration truly an exciting creative platform for meaningful cultural exchange between China and France."

Reader's Digest: The Power of Music - Lara Downes reflects on the beautiful soundtrack to her life

How Billie Holiday showed Lara Downes the beauty in hardship. Published in Reader's DIgest.

Reader's Digest

By Lara Downes

Photo: Anthony Tremmaglia for Reader's Digest

Every Saturday morning, when I was a little girl, my sisters and I went to the San Francisco Conservatory of Music for what we called Saturday classes: piano lessons, theory, music history—serious classical music training for serious little musicians. After we got home, we had a ritual. We’d get out our “dress-up” from the vintage steamer trunk that housed a collection of my mother’s 1960s party dresses and my grandmother’s furs, go through my parents’ record collection—the Beatles, Sinatra, Charles Aznavour, Nat King Cole, Billie Holiday—and dance around the living room. The Billie Holiday records stopped me in my tracks. I was enthralled by Lady Day, her dark eyes shaded by a white gardenia, her world-worn voice, and the mood and phrasing, line and color that she brought to even the simplest tune.

In my diary, when I was eight, I made a careful list in perfect cursive of all my favorite things. My favorite song was Billie Holiday’s “I Cover the Waterfront”—such a sad song, about watching and waiting for a love that’s gone. That year was the last year of my father’s long, slow dying. After he passed away, I spent foggy afternoons at the window, looking out over the San Francisco Bay, waiting for the grief to lift. I pulled out the old records at night. “I cover the waterfront,” Billie sang. “I’m watching the sea / Will the one I love be coming back to me?”

My father was born in Harlem and grew up steps from the clubs where jazz blossomed in its golden age and where Billie Holiday was singing during his childhood. He loved jazz. In my earliest memories, he is listening to records, the long length of him stretched out in our living room. In the end, he left us the memories and the records.

Our family buried our loss in our music. My mother took me and my sisters to Europe, where we lived in the great capitals and studied at the great conservatories with the legendary artists of a quickly vanishing generation. It was a very different life, surely, than the one my father had imagined for us. American culture was something far away, accessed through overdubbed TV reruns, the occasional jar of peanut butter from an Army base commissary, and the cheap East Bloc bootleg jazz CDs we bought at open-air markets.

My sisters and I were growing up. I had my first love affairs. I spent one cold winter in Vienna practicing Schumann all day and listening to Billie Holiday records all night, missing a boy an ocean away. Schumann and Lady Day both knew a thing or two about heartache. “I’ll be looking at the moon, but I’ll be seeing you,” she sang.

Ten years later, I moved back to the States. I made my way, very alone, through the unknown landscape of the New York music world. I was starting over, and it was hard. There were moments of despair and defeat. I practiced Ravel and Liszt all day in a windowless sublet and listened to Billie Holiday records at night. “Beautiful to take a chance,” she sang. I found new courage and took some chances and had some astonishing luck—a competition win, a Carnegie Hall debut recital, a recording contract.

I was hungry for American music, for a reconnection with what was home. I played music by Copland, Gershwin, Bernstein, Ellington. There was something I needed to find in a musical tradition “beyond category,” as Ellington put it—a musical sea made of waves of immigration and tides of change. This distinct sound, from the concert halls to the clubs, spoke to me because it is everything we are, coming from so many different places and people.

On my bedside table I have two posed studio photographs from the 1930s. My two grandmothers: Grandmother Fay, one of seven sisters born to Jewish immigrants from the town of Belz in Ukraine, who grew up in Buffalo, New York, and came out to San Francisco when my mother settled there, who lived just a few blocks away from us when I was little but whose story I wish I knew better. And my Jamaican grandmother, Ivy, who moved as a young woman to Harlem, who died when my father was very small, and whose story is lost to family history and memory except for the equation of nose and cheekbones that I see whenever I look in the mirror.

My story of race and roots is captured in these two faded portraits. Two women, looking out at me in the bloom of their youth, framed inside the parameters of a time in which a relationship between them would have been buried under layers of impossibilities and prejudices. Looking into their eyes, I see proof of how much change has come in two short generations, how very recently their granddaughter’s version of American life became possible.

My parents met at a sit-in in San Francisco in the mid-’60s, and they dreamed for their three caramel-colored girls of a future color-blind America in which race wouldn’t matter. But, of course, it did. From the beginning, I was well aware of the undercurrent of racial complexities and complexes that run through our culture. Being caramel colored in America comes with a burden of confusions, assumptions, and questions. Living abroad shifted that burden, but when I came back, I felt it again.

A musician is born and then made. Everything folds together: all the music you hear, study, practice, and perform, all the lessons you’re taught and the ones you learn on your own. So when I decided to pay tribute to Billie Holiday by recording a piano album of her songbook, I had to take a hard look at this lifetime I’ve lived with her music. I had to turn back to the nights when her voice had sung me out of sadness to sleep, back to those Saturday afternoons of my childhood, and to ask myself what I’d learned from her, as a musician and a woman.

She was one of the most innovative and distinctive musicians of any genre. She was a brilliant, mesmerizing, self-destructive woman whose life swung from tragedy to triumph and back again. Her voice spoke volumes about hard living and heartbreak and about improvising your way through it all. She took a song, any song, and made it immediately and forever her own. She didn’t follow anyone’s rules. “If I’m going to sing like anyone else,” she said, “then I don’t need to sing at all.”

When I was eight, Billie Holiday’s music taught me that something beautiful could be made from sadness. For a musician, that is one of the most powerful lessons to learn. It’s what saves us. She lived a short and troubled life, but the happiness and luck that she did find, she found through music. And finding your joy and strength in music is something I know. I know what it’s like, when things have fallen to pieces, to put on a satin dress and go onstage and find the secret power of a woman in a satin dress and make your listeners fall in love with the music. Just like I fell in love with Billie Holiday’s songs.

She gave away her heart boldly and foolishly, and every time it was bruised, she turned that pain into something graceful and moving, in a song. “Love is funny or it’s sad, it’s a good thing or it’s bad,” she sang, “but beautiful.” There have been times when I’ve given my heart at the wrong time to the wrong man. One spring I played Rachmaninoff during the day and listened to Billie Holiday at night. “I’m a fool to want you,” she sang, a phrase I echoed in my head.

It’s been hard to hold on to hope this year. I’m raising a caramel-colored boy of my own and would like to think that my parents’ dream can come true for him. But I am afraid it is still out of reach. I’ve been sad and turned to the music that taught me how to find the beauty in pain. I’ve been playing Billie Holiday songs across America with my musician’s voice reaching back to join hers. I’ve met people who heard her sing in Harlem when my father was a boy, people who were her friends and lost her too soon, people who have lived their whole lives with her records, as I have.

This music has made me new friends, told me new stories, brought back things I thought I’d lost a long time ago. It’s brought me home. After all the years, all the travels, all the music, I’ve understood the lesson I’ve learned from Lady Day: that the magic in making music, as in living life, is to forget about all the definitions and rules you ever learned, to lean back against the launchpad of your history and your experience, your losses and heartaches and joys, to look out into the future and to make something that is completely your own. Something that reaches deep to your center and pulls out a truth powerful enough to illuminate the moment and to shine far ahead, into memory. Something unexpected, something indefinable, perhaps complicated, but beautiful.

Listen to the music that inspired this essay here.

New York Classical Review: Long Yu Leads New York Philharmonic in Chinese New Year Program

The Philharmonic played brilliantly, sounding secure and powerful under Long Yu’s baton, and the performance of the solo part by the Philharmonic’s principal harpist, Nancy Allen, was exquisite.

Photo: Chris Lee

New York Classical Review

By Eric C. Simpson

The New York Philharmonic’s fifth annual Chinese New Year celebration on Tuesday night was something of a riddle. On the one hand, there was a ninety-minute program with a sought-after violinist, a stage address from United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, and no intermission suggested an emphasis on providing entertainment for the gala patrons whose tables were being set on the promenade outside the hall.

On the other, the most substantial item on the program by far was the New York premiere of a forty-minute piece from the last decade that proved as artistically and intellectually stimulating as anything the Philharmonic might present on a regular subscription concert.

The first music of the evening was certainly more in the former spirit, like any good concert overture: Li Huanzhi’s Spring Festival Overture, composed in 1955-56, is a peculiar product of the early years of Western-style composing in China. Li’s darting melodies and galloping energy, combined with a Romantic idiom, almost conjure reminiscences of something between the American West and a Parisian Can-can. Under the direction of guest conductor Long Yu, the music was dignified, but not humorless.

More substantial, though opaque in its own way, was the famous The Butterfly Lovers, a violin concerto written jointly by Chen Gang and He Zhanhao just a few years after the Spring Festival Overture. The soloist on this occasion was Maxim Vengerov, who a decade ago was at the top of an intensely competitive field before an injury forced his career into hiatus. Technical problems, such as murky passagework and wandering intonation, linger, but the most attractive elements of Vengerov’s playing are the ones that always stood out: the effortless warmth of his tone and keen expression of his interpretation.

The Butterfly Lovers offered the violinist ample opportunity to demonstrate these two qualities. The concerto has its stretches of showy virtuosity, but at its core it is an innocently lyrical piece, lightly orchestrated and unassuming, its solo part taking inspiration from traditional Chinese instruments rather than Romantic violinistic flair. Vengerov’s interpretation was poignant, finding moments of intense passion in the gleaming lines without ever hurrying them

Less successful was Vengerov’s performance of the Kreisler chestnut Tambourin Chinois, a fleeting bonbon that served essentially as a programmed encore. A master of pastiche, Kreisler in this brief showpiece combines Chinese musical idiom with violinistic fireworks of considerable difficulty—too much difficulty, apparently, for Vengerov, who rushed through the piece and failed to convey much its charm.

After the relative pleasantness of the first forty minutes, hearing Tan Dun’s The Secret Voices of Women was like stepping into an ice bath. Though the composer calls the piece a “Symphony for 13 Microfilms, Harp, and Orchestra,” there are no microfilm readers called for in the score; rather, “microfilm” is his name for a series of short films he has captured and edited of women in rural China singing traditional Nu Shu songs, cataloguing folk melodies in danger of being lost. Around these, Tan Dun constructs what is essentially a harp concerto, drawing inspiration from the songs and echoing them in his writing for orchestra and soloist.

At times, the writing takes the form of a simple and comfortably harmonious accompaniment, whether in the form of light pizzicato and percussion or burnished strings. At others, the echoed vocal melody becomes a maddening refrain, dissolving into interludes of shivering ice or harrowing fury.

The video scenes themselves are emotionally affecting, portraying mostly elderly women in a variety of activities, projected in three different frames above the stage. One in particular shows a song of ritual mourning, accompanied by frantic worrying in the solo harp. The songs are presented without any English text, a choice that avoids distracting from either the images or the music. One feels that Tan Dun made the correct decision here, though undoubtedly many audience members missed a layer of the work as a result.

The Philharmonic played brilliantly, sounding secure and powerful under Long Yu’s baton, and the performance of the solo part by the Philharmonic’s principal harpist, Nancy Allen, was exquisite. Tan Dun’s writing for harp is extremely demanding, not just in degree of difficulty, but in its length and relative continuity. More than equal to the technical challenges, Allen brought a strong voice to the varied solo line. Would that every gala concert left so strong an impression.

Washington Post: Julian Rachlin in Washington with Orchestre National de France

"And when Rachlin got going into the final cadenza, he became a wild thing, a kind of inspired mad scientist in a monologue both profound and terrifying..."

Washington Post

By Anne Midgette

I confess I wasn’t very excited about going to hear the Orchestre National de France play a program of chestnuts on Sunday afternoon. Evidently, a lot of other music-lovers shared my sentiments, because the Kennedy Center Concert Hall was only about half-full.

Why, after all, should we want to hear the Orchestre National de France? It’s partly the presenter’s job to let us know. And indeed, Doug Wheeler, the president emeritus of Washington Performing Arts, answered in his brief and on-point remarks from the stage before the show: because the orchestra was among the first that the organization’s founder, Patrick Hayes, presented in Washington even before Washington Performing Arts came to be, and the two institutions have had a long and fruitful collaboration ever since. [Ed: The previous sentence has been corrected; it originally misstated the date of Washington Performing Arts’s founding.] Maybe knowing that would have incited a few ticket-buyers; as it was, it was a bit of too little, too late.

Why else? Because their music director, Daniele Gatti, is a heavyweight in the conducting world, and will take over the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, one of the world’s greatest ensembles, when his contract with this group ends at the end of the current season.

But we couldn’t have known some of the other reasons beforehand. For instance: because Julian Rachlin, the violin soloist in the Shostakovich first concerto, is a veritable force of nature who turned out to be the centerpiece of a searing performance of that work. And because everything the orchestra played on Sunday was pretty remarkable — even for those of us who said beforehand that we had heard Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony done so often, and done so well, that we had no desire to hear it again any time soon. (An awful lot of my job these days seems to involve defending fine performances of over-familiar works.)

Gatti is a formidable presence on the podium: visually, he conveys a sense of physical power, so that his delicacy and restraint and detail take on a kind of implicit force. He used this to full effect throughout hte afternoon, starting with an exquisite, languid, idiomatic performance of Debussy’s “Prelude to the afternoon of a faun,” in which every instrument offered precision while maintaining the soft, fluid contours of this score.

But it was the Shostakovich that was the real tour de force. Rachlin, the violinist, is a small contained firebrand of a man onstage, and he eased his way into the opening movement with playing that was almost painful in its muted restraint, over the humid, brooding chords of the orchestra. The second movement then uncurled into some of the most biting fierce Shostakovich playing I can remember hearing. And when Rachlin got going into the final cadenza, he became a wild thing, a kind of inspired mad scientist in a monologue both profound and terrifying, until the orchestra finally chimed in with ferocious clashes of regretful understanding.

I didn’t even need to fight to lower my defenses against the Tchaikovsky; Gatti and the orchestra simply leveled them, with authoritative, urbane playing. Gatti even nodded to the piece’s familiarity by leaving off conducting entirely at times, keeping himself to the most minimal of gestures even in the final movement, which nonetheless seemed informed by the Shostakovich that had preceded it: more abrasive and aggressive than a triumphant resolution.

So those of us who went to this concert were pretty happy we had gone. Now, Washington Performing Arts is looking for ways to convince you that you want to go hear Ivan Fischer and the Budapest Festival Orchestra, who arrive with Marc-André Hamelin and a slightly less overworked program on February 15th. You can get tickets at a 50% discount now.