Billboard: Meet Pablo Villegas, Global Ambassador of the Spanish Guitar

The rambling man in a tuxedo will play Brooklyn's National Sawdust before joining Placido Domingo tribute.

Billboard

By Judy Cantor-Navas

Pablo Villegas performs Thursday (June 2) at Brooklyn venue National Sawdust. After that, he’ll be part of a huge tribute to Placido Domingo at Madrid’s 80,000-capacity soccer stadium, presented by Champion League winners Real Madrid’s foundation. Then Villegas will be playing for children at the Vivanco Museum of Wine Culture in Spain’s La Rioja region, where he is from, before spending the summer on a symphony tour in Japan. Villegas will return to the U.S. in the fall for gigs at Princeton University and Philadelphia’s Kimmel Center.

You may not be familiar with Villegas, but, as witnessed by his schedule, it’s safe to call him a global ambassador of the Spanish guitar. A frequent classical orchestra soloist, the New York-based musician describes himself as “carrying his guitar on his shoulder and a suitcase in his hand;” sort of a rambling man in a tuxedo.

The guitarist delved into diverse genres of popular music from Latin America and the United States for his most recent album, Americano. The 2015 release debuted at No. 11 on Billboard’s Classical Crossover Chart.

We caught up with Villegas at a hotel in Panama City to talk about the guitar’s journey through the Americas, and his own quest “to present the guitar almost like a new instrument, starting with the sound.”

Despite the important history and beauty of classical guitar music, on a massive level it’s become a kind of background sound associated with “chillout” mixes. How have you proposed to take it – or take it back - to another level?

The guitar is an instrument that’s tied to a specific culture, Spanish culture. At the same time, it has became one of the most international, popular and versatile instruments in existence. It has that duality. Spanish guitar - classical guitar - and all of its repertoire is one of the most difficult and sophisticated, musically speaking.

My intention is to present the guitar almost like a new instrument, starting with the sound. The guitar is an instrument that has not been considered a main player in an orchestra setting. I’m presenting it as a symphony instrument to play with an orchestra, without amplifying it. [I want to] project a big sound.

When I play a concert, people always say, ‘I never heard the guitar sound the way that you play it.’ And that is exactly what I am looking for. We’re talking about an emotional connection through the music using the guitar. For me, the guitar is the most wonderful and expressive instrument.

In addition to your classical concerts in which you play music by the great Spanish composer Joaquín Rodrigo and others, you’ve been exploring some more international and popular repertoire with songs you showcase on your album Americano. How did you come up with the concept?

It started when I met John Williams in Los Angeles. He invited me to his house because he had composed his first piece for solo guitar, and I was so fortunate that he asked me to perform the world premiere of the work (in 2012). Then I asked him if I could record it. From there, the seed of Americano was born. The guitar is tied to Spanish culture, [but] it is an instrument that belongs to the Americas as much as it does to Spain. Because once the guitar got to the Americas in the 16th and 17th centuries, it became the one through which all of the different regional identities in each country could be felt. There are dozens and dozens of rhythms that have their own identity. It was so exciting for me to explore what you can call the “American guitar.”

The tracks range from a Venezuelan joropo to an Argentine tango, to “Granada” by Mexican songwriter Agustín Lara and “Maria” from West Side Story. How did you choose?

I wanted to establish a context from which I could take a trip from the south to north, until I arrived in the United States, exploring the music of composers from different countries...I also wanted to transmit the vision of music as something that unites people. It’s a universal language, from American bluegrass to Brazilian bossa nova.

It was hard to decide what to include. I ended up leaving a lot of pieces out.

You’ve become well-established on the classical circuit and beyond [at age 38], but how did you begin your career?

I went onstage for the first time when I was seven years old. It was in a theater in my home town, Logroño, in front of an audience of family and friends. From that day on I wanted to play. My mother and I had the idea of performing at senior citizen residences on the weekends

The people in the audience are the ones who make sense of performing – and it’s the same whoever you are performing for. For me, it can be children I’ve played for through my work with my foundation (Música Sin Fronteras), or playing at Carnegie Hall. It’s the same thing.

The magic occurs with the music of the composer, the performer and the audience. That is the musical trinity. When it connects it’s something magical. It’s something we’ve all experienced at some point when we listen to music.

Tell me about your relationship with Vivanco, the celebrated winery in the La Rioja, the famous Spanish wine region where you grew up...

Vivanco has very close ties to art and culture. They have a foundation with a wine museum that UNESCO considers to be the most important one in the world dedicated to wine culture. We began this collaboration of support and sponsorship. It’s a natural relationship for me. Being from La Rioja, it’s easy for me to promote the culture of the region and its ties to wine and history. And there are a lot of receptions after my concerts...

Strings Artist Blog: Julian Schwarz: I Play the Cello. Should my Teacher?

Since I was a child, I have studied cello with cellists. Makes sense, right? A cello teacher knows how to best hold a cello and a cello bow, place his or her fingers on the fingerboard, play in thumb position . . . the list goes on and on. The technical expertise of a cello teacher is undeniable, but what about the music?

Strings Artist Blog

In addition to the great lessons I have received from cellists throughout the course of my musical education, I have also been consistently challenged by players of other instruments. Growing up I had musicians at my disposal. I would play for my father [trumpet player and conductor Gerard Schwarz]. I would play for my mother. They would offer musical insight beyond my maturity. They would listen to my playing from a musical perspective, not a cellistic one. This would be incredibly frustrating.

My father would ask, “Why are you making that nuance?” I would reply that it was because of some technical consideration. He would not be satisfied with that reply. He would continue, explaining that if a certain technical consideration yields a musically uninspired result, then the technical consideration should be overcome another way. As a child who often spoke back, I would exclaim, “Dad, you just don’t get it.” I was unwilling to take on a huge technical burden for a seemingly minute musical improvement.

Boy, was I wrong.

As I matured, I started to realize that I was consistently challenged most often by non-cellists. Cellists would understand why I would not vibrate the note before a shift. They would understand why I made an unnatural crescendo to the frog. They would often show me the easy way to play a passage. As I grew, I started to see beyond these accommodations. Though it was nice to have someone listening to me that would accept some rocky intonation because he or she “knows how nasty the passage is,” I started to seek out those who wouldn’t accept it—those who wouldn’t understand.

Two violists come straight to mind. I had the great fortune to learn from two distinguished professors of viola during my time as a student. They began as chamber-music coaches. They were consistently demanding— to my great joy and admiration. I started to play for them alone. They would see and hear things I had not. They would ask me why I had made a musical decision, regardless of technique. Taking a lot of the technical considerations out of the equation was the absolute best learning experience I could have had. The lessons were about music, and only music.

Of course it is undeniable that a certain technical level should be achieved prior to taking lessons from teachers of other instruments, yet many of the technical advances one can make will only come to fruition if certain musical nuances are demanded. I remember many a time when one of my viola gurus would ask me to play a phrase a certain way. I would have trouble. That trouble would nudge my rear end to the practice room, where I would solve the technical issue that prohibited my expressivity. How incredible that I had that opportunity.

Though the two violists with whom I studied greatly inspired me musically and, as a result, technically, I did not stop there. I started to play for whoever would listen—but no cellists.

Conductors are a fantastic resource, as their musicianship is never (or should never be) confined to one instrument or one family of instruments. Pianists are also interesting, as they aim to create a large range of color on an instrument rather limited in this respect. Wind players and vocalists can educate string players about the sense of breathing that is inherent in all music.

There is also an important element of a teacher-student relationship one can omit by bringing music to teachers of other instruments: ego. Even though many teachers try to avoid direct competition with their students, there is an element of competition that is unavoidable if a teacher and student play the same instrument. Enough said. Playing for other instrumentalists will avoid this issue, or at least reduce its impact on the teaching itself.

Repertoire plays no part in this exploration. I would not bring only the Schumann Fantasy Pieces to a clarinetist (the fantasy pieces are clarinet works commonly played on the cello since Friedrich Greutzmacher made a transcription in the 19th century). Quite the contrary. I would not bring the Schumann Fantasy Pieces to a clarinetist because I would be looking for a musician’s take on my repertoire, therefore avoiding established traditions and opinions in my pursuit of musical integrity.

In the end, technique should never impede musical considerations—and without specific knowledge of a piece’s mechanics, a non-cellist will best judge your musicality. There is no such thing as a bowing that cannot be achieved on the cello, just players who don’t care enough to put in the extra effort. I have been asked often by cellists about one of my fingering or bowing choices that they consider unnecessarily difficult. Musical intention always comes before difficulty.

If it sounded the same I would do it the easy way, but it almost never does.

Read the original Strings posting here.

BBC Radio 3 In Tune: Anne Akiko Meyers Performs Live

Listen here to Anne Akiko Meyers who performed Arvo Pärt's "Spiegel im Spiegel' and Bach's "Air" from Orchestral Suite... Read More

Listen here to Anne Akiko Meyers who performed Arvo Pärt's "Spiegel im Spiegel' and Bach's "Air" from Orchestral Suite No.3 in D major on BBC Radio 3 In Tune and talked with Suzy Klein about her new recording, broken foot, and Vieuxtemps Guarneri. Her segment begins at 42:22.

Strings Artist Blog: Cellist Julian Schwarz on Destiny—Tied with a Bow

For a string player, a great instrument is only half the equipment battle. A phenomenal bow is the other half, providing finesse, tone, and various articulations.

Strings Artist Blog

For a string player, a great instrument is only half the equipment battle. A phenomenal bow is the other half, providing finesse, tone, and various articulations. Bows are not only vital to phrasing and color, but sometimes suited to particular playing styles. Therefore it is common for an instrumentalist to own many bows to facilitate stylistic shifts. A bow collection is also much more affordable for string players than an instrument collection.

I find it interesting to try bows of various origins, weights, and styles, regardless of my intent to buy. This brings me to my story—one that starts with neither an intention to try, nor to buy, a bow.

One day I found myself at the Tarisio auction house in New York City (a premier auction house for stringed instruments and bows based in NYC and London) to return an instrument I had been trying that week. There was an auction only a few days away and the office was bustling with eager buyers. One such buyer was a Russian man who noticed me carrying a cello case. As I was making my way out he asked, “Are you a cellist?” I replied in the affirmative. He continued, “Would you consider helping me by trying the various cellos so I can hear how they sound?”

That afternoon I had neither appointments nor engagements, and I thought this exercise could be fun, not to mention a good deed!

So we went to a room and he brought me the first of many cellos to try. I sat down and realized an obvious obstacle—I had no bow! As I was just returning an instrument, I hadn’t bothered to bring one. As the auction had many cello bows as well as cellos, the gentleman agreed to fetch me a bow from the auction. He did so in haste—he was very considerate and appreciative of my aid and time. So I began.

As this was for his benefit, I played the same few excerpts on each cello, not aiming to draw conclusions myself. He took notes on each instrument’s unique sound, and asked for my thoughts occasionally. Turns out he was sent by another Russian man to examine the offerings of the auction. This other man was a collector, and relied heavily on the advice of my new friend.

As I played, I began noticing one common characteristic: the bow was a superb implement. I took a look at it. The tip looked like a Dodd (a very well-known English bow maker with a distinct style). I was fascinated by the bow as I stared it up and down. It was beautiful.

While trying more instruments, I started to simultaneously try the bow with more intent. I chose excerpts based on challenging bow techniques to see how well it responded.

It was absolutely brilliant.

After a few more cellos, my curiosity got the better of me and I just had to know what kind of bow it was. I assumed it was something very expensive—a Dodd of the highest order. I was guessing an auction estimate of $15,000–$20,000. I asked my friend to look up the lot number in the catalog. He showed me the entry. It was described as an “English bow with a stick attributed to James Brown and an unknown frog. Estimated $2,000–$5,000.”

My jaw dropped. It was not by a famous maker, did not cost an arm and a leg, and was a composite (meaning that circumstances required part of the bow be remade by another maker at a later date). This was not a bow for a collector. This was a bow for a player, and I loved it.

Elated, I sincerely asked the gentleman to refrain from bidding on the bow when the auction itself opened. He was glad to oblige. “This is your bow!” he exclaimed.

The day of the auction arrived and I was ready. I had never bid on a bow or instrument before. Auctions had always fascinated me, as I was dragged to many as a child—all to furnish my childhood home with antiques—but I had never participated myself.

I created my Tarisio account and realized that the auction had already finished.

What? Really?

It was 4 o’clock pm and I figured that I would get in before a 5 o’clock closing. But 5 o’clock pm in London is 11 am in New York. I was 5 hours late. There it was, my opportunity to get a great bow—a great steal—gone. I was disappointed, to say the least. Out of sheer curiosity I examined the lots to see at what price points various items closed. Out of over 300 lots, 298 sold. That left me a shred of hope. I went through hundreds of lots before landing on cello bows.

My dream bow had not sold. I got on the phone right away, spoke to the auction house, and the bow was mine. Hallelujah! What were the odds? The only cello bow not to sell was the only one I desired.

Not only did I purchase the bow for the minimum accepted bid, but I received a reduction in the buyer’s premium, as I was the first in and first out. What fortune! What luck! I was on cloud nine. My Russian friend had been true to his word. Bless his heart.

To add more joy to the situation, I removed the frog after picking up the bow from the auction house only to find a stamp on the inner part of the frog that read “Paul Siefried.” Paul Martin Siefried is one of the most respected bow makers in the world, and made my first full-size bow my parents bought me when I was 10 years old. Not only was it a welcome surprise, as I had been playing a Siefried for 14 years, it also increased the value of the bow.

A few months passed and I still loved the bow. I played all my spring and summer concertos, recitals, and chamber performances with it. It had everything—projecting tone, subtlety, and color to spare. One night I was set to have dinner with my parents and the widower of my cello teacher from high school. Toby Saks was a remarkable cellist and a remarkable woman. She was hard on me, that’s for sure, but she believed in me and gave me immeasurable tutelage of the highest order. She was a huge inspiration, and I always sought her approval and appreciation. She was a huge part of my musical life, and I am so lucky to have known her and studied with her. Our close relationship made it all the more difficult for me when she passed away suddenly in the summer of 2013. She left behind an amazing husband Marty, and I was set to have a meal with him and my parents in New York.

We met at my parents’ apartment and began to catch up. I always liked him, and it was good to see him since I had had little contact with him following Toby’s passing. Eventually the conversation turned to Toby, and it was very meaningful to me. I was able to express to him how much she meant to me both personally and professionally. He affirmed that, though demanding of me, she was proud of what I had accomplished in her lifetime.

Then I felt I had to ask the question I had been meaning to ask for two years but felt ashamed to ask in the face of such tragedy. “So…” I hesitated, “what happened to the bows?”

Toby had a superb collection of fine French, American, and English bows that she never allowed me to either see or play. She would not even divulge how many bows she had or who made them. All I knew is that it was an important collection.

Marty replied flippantly, “I sold them all.”

I was in disbelief, and retorted sarcastically, “Thanks for calling me!” and followed it up with a huff. He was shocked at my reaction. “I would have jumped at an opportunity to buy one of Toby’s bows,” I said.

Silence followed.

After a few moments, he said (with much sincerity), “I am so sorry.” There was nothing else to be said. He had to sell the bows. I knew that. Toby had children from a previous marriage and her assets had to be liquidated. I understood that, but I was emotional. I wanted a piece of Toby for the ages. She left this earth much too soon and I missed her. I wanted to feel a connection, albeit to something inanimate.

I calmed down. The air became less tense and I inquired as to where the bows went, to whom, and who made them. He went through the list, which was quite impressive, and went through who had a part in selling various parts of the collection. He concluded, “All the rest of the bows that weren’t sold I put in the Tarisio auction this past May.”

Wait . . . it couldn’t be. My mind started racing. “Did all the bows sell?” I uttered, as I tried to reign in my potential excitement.

“There was one bow that didn’t sell,” he replied, “but then someone bought it later in the day, which was great because I don’t know what I would have done with it.”

Paul Siefried made the frog. The lot numbers matched.

I bought Toby’s bow.

Cellist Julian Schwarz made his orchestral debut at the age of 11 playing the Saint-Saëns Concerto No. 1 with the Seattle Symphony with his father, Gerard Schwarz, on the podium. He has performed with symphonies and in chamber-music festivals throughout the United States and internationally. He was awarded first prize in the professional cello division of the inaugural Alice and Eleonore Schoenfeld International String Competition in Hong Kong, and received his bachelor of music degree from Juilliard, where he studied with Joel Krosnick. He is pursuing his master of music degree, also at Juilliard. Schwarz performs on a cello made by Gennaro Gagliano in 1743.

Boston Globe: Watertown bow maker practices musical alchemy

“It’s just amazing,” says Lowe, the BSO concertmaster. “Some people look at a note or phrase of music on the printed page and ask, ‘Oh, how does it do that to my heart?’ For me, it’s the same thing, but I look at a tree and think, ‘How does Benoit turn this into a bow?’ ”

Boston Globe

By Jeremy Eichler

Yo-Yo Ma remembers preparing to be diplomatic. His wife had just surprised him with a newly commissioned cello bow for his 60th birthday.

Such a lovely gesture, he thought, while at the same time feeling slightly skeptical. He already played on a 19th-century bow by the most revered maker in history.

Ma’s friends, who had gathered last fall for a festive birthday dinner, zealously insisted that he give the new bow a try. So he did.

“In a few seconds,” Ma recently recalled, “I switched from being polite, to being like, ‘Oh.’ ”

His friends reached for their cellphones.

“We were all just floored by the clarity and projection and the color this new bow was producing,” said David Perlman, a friend of Ma’s who was present at the dinner and had helped engineer the gift. “There was just something electric about it, something that was totally unique.”

Benoit Rolland, the maker of this mysterious new bow, was not present on this occasion. But, curiously enough, neither was he far away.

Born in Paris, Rolland learned his art in the French town of Mirecourt, the storied center of the French instrument-making tradition. You might expect to find him now in a well-appointed shop on a leafy side street in one of Paris’s more elegant districts.

In person, Rolland, 61, exudes an air of calm and a keen intelligence that seems to concentrate behind his warm, watchful eyes. He is quick to apologize for his English, but nonetheless speaks with a streamlined eloquence about his personal approach to his art. “The violin makes the sound,” he likes to say, “but the bow makes the music.”

A trained violinist, Rolland asks to hear a musician play before beginning a new commission. Listening carefully, he then forms what clients describe as an almost eerily insightful picture of a musical personality: one that can encompass the specific expressive contours of a performer’s style, and perhaps even hidden potentials waiting to be unlocked by the right bow.

“He has a great gift of watching and sensing,” says Mutter, by phone from Austria. “It’s more than only knowledge.” The Boston-based Kashkashian concurred: “I don’t know anyone who hasn’t felt that he captured what they needed,” she said.

To match bow to player, Rolland works meticulously to select wood with the right density and sensitivity to vibration; he then tapers, shapes, and cambers the stick according to a particular balance he deems right.

Most recently, however, Rolland has been channeling his mental, physical, and spiritual resources for a client more discerning than most: himself. Rolland in December began the bow — his 1,500th creation — that he sees as a kind of personal celebration.

For it, he has used an uncommonly beautiful and resonant piece of Brazilian Pernambuco wood he had been saving for years, and the rarest ebony from the island of Mauritius, given to him by his teacher, Bernard Ouchard, almost a half-century ago.

In the new bow’s frog — the rectangular part at the base of the bow that moves to control its tension — he placed mother of pearl he harvested himself from a French island off the coast of Paimpol. The frog has been adorned with two diamonds and a delicate gold inlay inspired by a painting of a swallow by his wife, the painter and poet Christine Arveil.

This bow, he explained, would also be a celebration of their partnership. “For me, it is a way to gather all of the ideas I have so far about bows, and to put everything in one bow: this bow.”

When Rolland first elaborated on his plan and the delicacy of work entailed, with adjustments measured in hundredths of a gram and inlays that would require him to construct an entirely new set of tools, it seemed like an almost quixotic quest — as if a leading writer was fearlessly announcing that his next novel would be written on a grain of rice. But he seemed coolly undaunted.

He also spoke of his initial journey into this career and of his early years as a student, when the wood was “so hard, so hard” and it would cut into his sensitive violinist hands. Many times he considered abandoning the profession.

“In a way,” he said, “this is a celebration of a victory over myself.”

It is a strange fate to be a master of an art at once so essential and hidden from view. The public often hears of Stradivarius instruments; bows, by comparison, are rarely discussed. If you are not a string player or married to one, chances are you cannot name a single bow maker, living or legendary.

But without the bow, and its way of keeping a tense string in a state of perpetual excitement, the violin resembles a small, handsomely varnished guitar. “The bow is a very old concept,” Rolland offered one afternoon, sitting at his large oak workbench. “I don’t know, but I think it was born with the first human being, and the first wish to reproduce the human voice through an instrument. There is no way to do that without a bow.”

Yet this undisputed master of bow making has been quietly plying his trade for the last several years from a brightly lit home studio in a certain north-bank arrondissement of greater Boston, one that is perhaps better known as Watertown.

If you attend concerts in the area, chances are you’ve heard a player performing with one of Rolland’s creations. Recognized in 2012 with a MacArthur “genius grant,’’ he has made bows for several leading soloists on the circuit today — including violinist Anne Sophie Mutter and cellist Lynn Harrell — and for 20th-century legends such as Yehudi Menuhin and Mstislav Rostropovich.

He also keeps Boston’s own string players well cared for. In just one typical example, on Monday at New England Conservatory’s Brown Hall, a Music for Food benefit performance will feature no fewer than four prominent string players — violists Kim Kashkashian and Paul Biss, violinist Miriam Fried, and cellist Marcy Rosen — who rely on Rolland’s bows. So do about a dozen Boston Symphony Orchestra string players, including concertmaster Malcolm Lowe.

Yet to actually create a bow from scratch is to practice an odd type of alchemy, transforming what is essentially a hunk of wood and the hair from a horse’s tail into the conduit for the most sublime thoughts of composers through the centuries — and of the players who translate and interpret them.

“It’s just amazing,” says Lowe, the BSO concertmaster. “Some people look at a note or phrase of music on the printed page and ask, ‘Oh, how does it do that to my heart?’ For me, it’s the same thing, but I look at a tree and think, ‘How does Benoit turn this into a bow?’ ”

“Slowly” might be the first answer. Rolland works in an airy studio, his desk placed at an angle below a skylight. He uses many tools he built himself about four decades ago (“They don’t sell bowmaking tools in Home Depot,” he jokes) and others that he inherited from his teacher.

The French school of bowmaking, he explains, prizes physical contact with the wood itself. No power drill or vice is ever used. Rolland grips the bow with his strong left hand, often passing it over the length of the stick to feel its qualities but also, surprisingly, to listen.

“When you work, all the senses must be awake,” he said. “The sound of the wood will tell you if your plane is well-sharpened, if your wood is docile or rebellious, and if the wood is good for transmitting vibrations.

“This one has a very clear sound,” he continued, holding up the deep auburn stick that was to become No. 1,500. “It conveys vibration very fast, so it will produce a very bright sound.”

As for the basic physics of the bow, as Rolland explains it, the horsehair sets the string in motion, and the vibration is transmitted to the instrument. But the vibration then returns through the bridge back to the wood stick, creating a kind of closed feedback loop of sound creation.

Rolland says the ideal bow requires the harmonizing of opposing goals: strength and flexibility. It should also feel completely natural in the hand, “as if a piece of wood has been transformed into an extension of your own muscle.” In other words: countless hours of his work are invested in the creation of an object that, if he has achieved his goal, will effectively disappear.

Being invisible, however, should not mean taken for granted. “Composer, interpreter, and maker: they form three corners of a triangle,” Rolland says, his eyes brightening just before he turns back to his workbench. “Without any one of them, there is no music.”

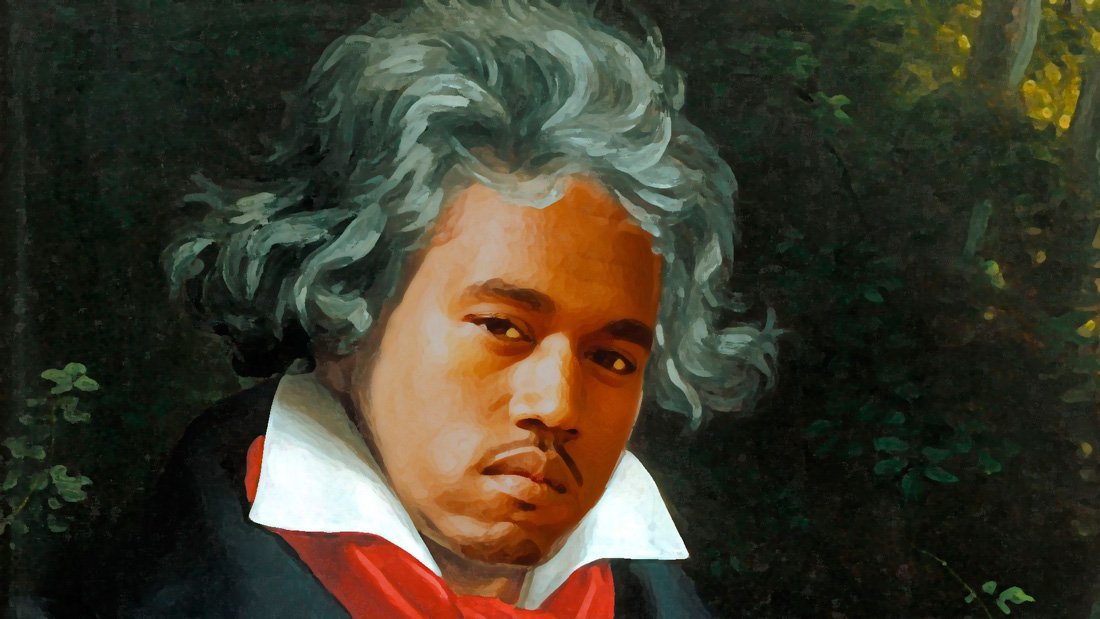

GQ: An Orchestra Is Mashing Up Kanye West’s Hits with Beethoven’s to Create “Yeethoven”

Los Angeles's Debut Orchestra of the Young Musicians Foundation is taking a bold approach to their Great Music Series, performing some of Beethoven's classic works alongside Kanye West's Yeezus to create the perfectly titled "Yeethoven." I'm sure it tickles Kanye's fancy to be put alongside someone as musically revered as Beethoven, but it actually works. While it seems a little strange, partially because the best part of Kanye's music is frequently, you know, Kanye rapping, when you listen to the preview, it makes sense.

GQ

By Nicole Silverberg

It's pretty epic

Los Angeles's Debut Orchestra of the Young Musicians Foundation is taking a bold approach to their Great Music Series, performing some of Beethoven's classic works alongside Kanye West's Yeezus to create the perfectly titled "Yeethoven." I'm sure it tickles Kanye's fancy to be put alongside someone as musically revered as Beethoven, but it actually works. While it seems a little strange, partially because the best part of Kanye's music is frequently, you know, Kanye rapping, when you listen to the preview, it makes sense.

Yeezus and hits by Beethoven, including "Egmont Overture" and "String Quartet No. 14 (op. 131)," are played alongside each other and reveal some striking similarities. The conductor Yuga Cohler explains that both Beethoven and Yeezy make music with a "brashness creating wild contrast, thrashing juxtapositions within a single bar of music," which isn't exactly what I think of when I'm listening to "I Am a God," but now that Cohler said it, I'm like, Oh, yeah!

Cohler said he chose Kanye and Beethoven because they both have a "willingness to ruthlessly abandon tradition, and their influence on that larger culture can't be overstated." Seeing as Yeezy is getting his own orchestral arrangements, I'm gonna have to agree. Just one question: Does this mean I have to start wearing gowns and pearls to his concerts?

Rolling Stones: 'Yeethoven' Concert to Juxtapose Music of Kanye West, Beethoven

On April 16th, Beethoven will meet Kanye West when a 70-piece orchestra mashes up and reimagines the work of the two artists. The program is part of the Great Music Series hosted by the Young Musicians Foundation.

Rolling Stones

By Brittany Spanos

The music of Kanye West and Beethoven will be compared and spliced up by a 70-piece orchestra during a Los Angeles concert.

On April 16th, Beethoven will meet Kanye West when a 70-piece orchestra mashes up and reimagines the work of the two artists. The program is part of the Great Music Series hosted by the Young Musicians Foundation.

Co-curated by conductor Yuga Cohler and arranger Stephen Feigenbaum, "Yeethoven" aims to show the commonalities between the seemingly dissimilar artists. "Obviously, they work within very different traditions," a voiceover reflects in the promotional clip for the concert. "Their willingness to ruthlessly upend tradition and their influence on the larger culture can't be overstated."

The concert will feature six works by Beethoven and six works from West's Yeezus that will be "juxtaposed" and "spliced together" by the orchestra live. It will be put on for free at the Aratani Theatre — Japanese American Cultural & Community Center in Los Angeles.

In 2012, a year before West released Yeezus, he compared himself to the classical composer during a concert in Atlantic City. "I am flawed as a human being. I am flawed as a person. As a man, I am flawed, but my music is perfect," he began. "This is the best you're gonna get ladies and gentlemen in this lifetime, I'm sorry. You could go back to Beethoven and shit, but as far as this lifetime, though, this is all you got."

Los Angeles Times: Kanye meets Beethoven: How young musicians are mixing classical with pop

It wasn't quite Little Coachella in Little Tokyo. But as if out of nowhere, more than 1,000 hip-hop fans, some wearing Kanye West T-shirts, descended on the Aratani Theatre. A few had arrived as early as noon on Saturday and waited in the hot sun for a 7:30 p.m. concert.

Photo: Kanye: Flickr/David Shankbone. Beethoven: Shutterstock

The Los Angeles Times

By Mark Swed

It wasn't quite Little Coachella in Little Tokyo. But as if out of nowhere, more than 1,000 hip-hop fans, some wearing Kanye West T-shirts, descended on the Aratani Theatre. A few had arrived as early as noon on Saturday and waited in the hot sun for a 7:30 p.m. concert.

Once the crowd had taken over San Pedro Street, the police came by to see what was going on. It was no big deal, they were assured, simply a queue for free tickets to the Young Musicians Foundation Debut Orchestra's Beethoven concert.

Make that Yeethoven, short for "Yeezus" (West's 2013 album) and Beethoven.

Meanwhile, not far away in Glendale, the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra sandwiched between the tame "Classical Symphony" of Prokofiev and "Clock" Symphony of Haydn a new cello concerto by Mason Bates, who has one foot in electronica and moonlights as a DJ.

Is something going on? Yes and no.

Every generation genre-bends, each in its own way. They always have and, no doubt, always will. Eyebrows go up and they go back down. But by now it has gotten pretty hard to shock.

What does seem new is the lack of controversy. One almost longs for the days when Parisians rioted the premiere of Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring," the Viennese practically threw Mahler out of town for smudging the sacred symphonic art form with street music, and the 1950s avant-garde horrified the establishment with pursuits that redefined the definition of music.

I heard the Sunday night repeat of LACO's program at UCLA, and for both this and the YMF event Saturday, the musical and social welcoming mat easily co-opted rebellion. Still, it is hard to complain about attaining, through music, a unifying feel-good mood in our otherwise divisive feel-bad times. "Yeezy season approachin'," West tells us. Could that be the revolution we need?

What made "Yeethoven" especially engaging was its unmistakably sincere musical roots. The Debut Orchestra, a training ensemble for instrumentalists and conductors founded in 1955, happens to boast among its alumni André Previn and Michael Tilson Thomas, famed for their groundbreaking mixing of symphonic and pop worlds. The 26-year-old Juilliard-trained YMF music director Yuga Cohler is in their mold, a self-proclaimed hip-hop fan since childhood who does not see that and Beethoven as worlds in opposition.

A young composer of like mind, Stephen Feigenbaum, served as "Yeethoven" arranger and co-curator. Six Beethoven scores were paired with songs from "Yeezus," each grouping given a theme — Form, Contrast, Harmony, Rhythm, Gesture and Will — representing qualities Cohler and Feigenbaum find shared across centuries and cultures by Beethoven and West.

Introducing the pairings, Feigenbaum noted the chaotic, over-the-top nature of Beethoven's "Egmont" Overture and West's "New Slaves" or the heroic yet ambiguous character of the snappy second movement of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony and "Hold My Liquor." These are, of course, all general enough qualities that you could make the same case for any number of composers.

In fact, dissimilarities could be more striking than similarities, beginning with an informal pop crowd that little resembled the formal musicians on stage. Neither do Beethoven and West sound alike. And while West does profess some of Beethoven's democratic ideals and confidence, there are also major differences, such as the pop star's attitude toward women so radically opposed to Beethoven's idealized "Immortal Beloved." And, of course, orchestra and pop concert settings have little in common.

Yet "Egmont" and "New Slaves" are, each in its own way, transgressive arguments for freedom. Putting West in orchestral dress and removing the vocals meant avoiding anything offensive. Were his language to be used in a traditional classical concert (or this newspaper, for that matter), there really would be trouble.

All but two of the pairs were mash-ups. Beethoven seldom upgraded West, rather West infected Beethoven with contemporary funk and spunk. The final mash-up mattered most. An orchestral arrangement of the last movement of the Opus 131 string quartet undercut Beethoven at his most spiritually transformative with the raunchy side of West in "On Sight." Cohler and Feigenbaum's theme was Will, but it could just as easily have been Impurity. Beethoven kept earthy, and West's music rose spiritually higher than you might have otherwise expected.

For the enthusiastic crowd (200 or more were turned away), every recognizable West hook got a shout out and Beethoven got respect. Cohler conducted with surety and security. The orchestra, though looking a little dazed in these surroundings, played with a joyful sense of making a history.

The crowd at Royce Hall on Sunday night was more standard issue for LACO, with but a few more young people than normal in attendance. (I wonder what would happen with audiences at UCLA if the school eliminated its $12 parking fee for concerts.) Much of the interest here focused on Matthew Halls, the British conductor who became music director of the Oregon Bach Festival two years ago and whose strong showing makes him a credible candidate in LACO's music director search.

An all-around early music guy whose recording of Bach harpsichord suites is a knockout, Halls also happens to be big on 19th century opera, symphonic blockbusters and contemporary music. He went for boldness in both Prokofiev and Haydn, getting some of the loudest playing I've heard from the orchestra.

But he put most of his attention on Bates' new Cello Concerto, which had its premiere earlier this year with the Seattle Symphony (conducted by Mirga Grazinyte-Tyla). It was written for Joshua Roman, who has his own street cred. The popular young cellist will, for instance, be playing at Amoeba Music on Wednesday, and he showed up at Royce in a showy print suit reminiscent of '60s Carnaby Street.

Bates is everywhere. The new composer-in-residence of the Kennedy Center (a first), he will have his next premiere streamed next week on the San Francisco Symphony Facebook page (believed to be a first for a major orchestra). He has lively orchestral imagination excellent for evoking specific sonic environments (such as primordial life or a future colony in Iceland) by adding beats and electronica effects to snappy melodies.

The Cello Concerto is more traditional. It includes instances of lightweight jazziness and commercial pop. It exploits Roman's flowery virtuosity and offers the cellist diverting light touches — such as bouncing the bow on the strings and plucking them with a guitar pick. But with Roman's propensity for cuteness, this concerto becomes less the transgressive expansion of our musical vocabulary than a contrivance suitable for taming the "monster about to come alive again" that West unleashes in "Yeezus" and Cohler cavorts with in "Yeethoven."

Washington Post: Anne Akiko Meyers: Violinist breaks a leg — or rather, a foot.

“Break a leg” and “the show must go on” are among the most overused injunctions in the performing arts. On Friday, Anne Akiko Meyers joined the lists of performers who have obeyed both.

The Washington Post

By Anne Midgette

“Break a leg” and “the show must go on” are among the most overused injunctions in the performing arts. On Friday, Anne Akiko Meyers joined the lists of performers who have obeyed both.

To be exact, she didn’t break a leg. She broke her foot. But it didn’t stop her from performing Mason Bates’s challenging violin concerto with the National Symphony Orchestra on Friday and Saturday nights (after Thursday night’s unhampered performance).

“I thought I just completely sprained my foot,” the violinist said by phone from her home in Austin, Texas on Monday afternoon. “It was black and blue. But I didn’t know it was broken. I have never broken anything in my body.”

On Friday night, all that was evident was a slight limp – and slightly unconventional footwear, sturdy platform sandals. (“They’re like wearing sneakers,” Meyers said.) Sitting in the audience, I might not have noticed either had I not been tipped, off the record, before the concert, that Meyers had had a bad fall in the afternoon. That explained the placement of a stool on stage; but in the event, Meyers walked out, did not use the stool, and played the difficult concerto with aplomb.

By Saturday morning, the foot had ballooned. For Saturday night’s performance, Meyers used a wheelchair to get on stage – but still played standing up.

“You cannot sit and play Mason’s music,” she said on Monday. “It doesn’t work.” Besides, she added, “If I had sat, I would never have gotten up.”

The accident itself was relatively benign, or perhaps “domestic” is a better term: Meyers was pushing a stroller with her two daughters, ages four and five, while checking her e-mail on a smartphone, and didn’t see the curb at the edge of the sidewalk.

“It happened at like two o’clock,” she said. “I had a soundcheck at four.” There wasn’t time to go to the doctor, and besides, she was pretty sure what a doctor would say: “You need to ice it, and elevate, and medicate: three things I couldn’t do at that moment.”

It wasn’t until she got home to Austin on Sunday that she went to the emergency room and discovered that she had played with a broken foot.

Her misadventure is reminiscent of the time in 2009 that the mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato fell on stage and broke her leg during a performance of “The Barber of Seville” at Covent Garden. DiDonato finished the performance, on crutches, and then went to the hospital. She sang the next performance in a wheelchair.

But opera staging involves so much physical activity that people are apt to get hurt once in a while. (I remember a night when the stage knife failed to retract when Don Jose stabbed Carmen, drawing blood from the mezzo-soprano Elena Zaremba. Fortunately he only hit her arm.) Generally speaking, the concert stage tends to be a less perilous place.

Meyers is not cancelling any performances. Next on her schedule is a recording in London of a new piece by the Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara, Szymanowski’s violin concerto, and Mortin Lauridsen’s arrangement of his popular “O Magnum Mysterium.” At least no one will see her footwear for that.

Huffington Post: Yeethoven Is The Kanye And Beethoven Mashup You’ve Been Waiting For

The Young Musicians Foundation Debut Orchestra, led by conductor Yuga Cohler and composer Stephen Feigenbaum, is bringing hip-hop and classical music together.

Photo: Priscilla Frank

The Huffington Post

By Priscilla Frank

The Young Musicians Foundation Debut Orchestra, led by conductor Yuga Cohler and composer Stephen Feigenbaum, is bringing hip-hop and classical music together.

When Kanye West released his sixth solo album, titled “Yeezus,” in 2013, he —with a single turn of phrase — fused his identity with that of the central figure of Christianity. The connection between Ye and JC was more than just an egotistical outburst from a narcissistic rock star, but a message about power, sacrifice, influence and vision, albeit a bombastic one.

Now, three years later, Ye has received another rather complimentary comparison. On April 16, at the Artani Theater in Los Angeles, the Young Musicians Foundation Debut Orchestra will perform “The Great Music Series: Yeethoven,” comparing Mr. West to Ludwig van Beethoven, and thus exploring the overlap between classical and hip-hop, 18th-century poofy collared shirts and 2013-era leather pants.

Yuga Cohler is directing the performance, along with project co-creator and composer Stephen Feigenbaum. The two, natives to the classical music world and longtime fans of Kanye’s work, have played music together since high school.

The Young Musicians Foundation Debut Orchestra is made up of 70 Los Angeles-based musicians between 15 and 25 years old. Cohler was appointed director last year. “I knew one of the things I wanted to do was make classical music engage with music of today, music that is very widely heard and massively popular,” Cohler explained to The Huffington Post.

From the beginning, Cohler and Feigenbaum were interested in “Yeezus,” the dark, grating, vinegary album that at once feels like a protest, a divine revelation, a nightmare and an industrial rave. “There are a lot of things in the album more reminiscent of classical than pop or hip-hop,” Feigenbaum said. “We tried to examine that and make that case that the commonalities across genres are more interesting than genre barriers.”

With “Yeezus” as a starting point, Cohler and Feigenbaum set out to find an unlikely musician whose sound reverberated with Ye’s. And if said musician happened to have an extremely punnable name, so be it. “We quickly came to Beethoven as someone similarly controversial in his time, someone brash and aggressive,” Cohler said. “Beethoven was rough around the edges. He’s one of the earliest examples of modernity, and often the audience really didn’t like it.”

They then began matching up Yeezus songs with analogous pieces from Beethoven’s oeuvre. For example, Kanye’s “New Slaves,” an epic harangue encompassing everything from systemic racism to fashion addiction, showed similarities to “Egmont Overture” in its dark, tumultuous energy. “In both songs, the endings are bizarrely uplifting, it almost feels bitter,” Cohler explained.

At first, the concert will juxtapose songs by Kanye and Beethoven to illuminate the comparisons aligning them. As the concert continues, the artists’ work will become ever more integrated, until the line between them becomes jagged and molten. “I think the boundaries we set up [in music] are necessarily artificial and don’t need to be adhered to,” Cohler said. Feigenbaum added: “We’re interested in getting out of the box that classical music puts us in.”

Although Cohler and Feigenbaum stress that their project is less concerned with the personas of the artists at play, and more concerned with their work, it’s hard to ignore the fact that, like Kanye, Beethoven was also something of an egoist. When a review of his “String Quartet No. 13” declared the work “incomprehensible, like Chinese,” he responded indignantly and without a hint of self-doubt, calling his audience “Cattle! Asses!” One of his most iconic quotes, “There are many princes and there will continue to be thousands more, but there is only one Beethoven,” sounds similarly familiar.

The show concludes with a comparison of the last movement of Beethoven’s “String Quartet No. 14” and Kanye’s “On Sight,” which opens his album. “If you don’t know the pieces you would have no idea where one piece starts and the other ends,” Cohler described. “It’s so emblematic of the artistic embryo that characterizes both Beethoven and Kanye — that propulsion, impulse and drive.”

Not everyone is psyched about the performance. Pitchfork Senior Editor Jayson Greene called the project “spectacularly ill-conceived.” Greene, who writes about both classical and hip-hop music, sees little connection between the two artists beyond a catchy conjoined nickname, and described the effort as a lazy attempt to bridge high and low culture that underestimates both artists and their audience.

“Lumping things on two sides of a room and drawing a line is less difficult than figuring out where each individual element belongs in a space,” Greene wrote. “And if you are going to start mixing and matching — say, by establishing a parallel between a rapper and a composer that leaps over genre boundaries, countries, and hundreds of years — for god’s sake, think hard about what you’re doing.”

Whether or not you like the resulting Yeethoven mashup, after speaking with briefly with both Cohler and Feigenbaum, it’s difficult to deny that they’ve put quite a lot thought into the pairing. This concert has been in preparation for about a year. And while Greene posits Igor Stravinsky as a stronger parallel to West, his argument is based as much upon the artists’ characters and visions as the actual content, which Cohler and Feigenbaum privilege.

As someone who knows far less about classical music, I cannot confidently comment on the solidity of the parallel between Ye and Be, at least not until the show takes place on April 16. However, I fully support the mission of a free, instructive concert performed by an orchestra of young people, illuminating bridges between unlikely artists that can be embraced or rejected by the audience as they see fit.

Rather than insulting their audience, Cohler and Feigenbaum invite people to participate in an imperfect experiment, one that can illuminate the tenuous nature of boundaries and categories confining all art forms. “The more young musicians that realize they can learn Bach and also improvise and play in a band and [learn that] those don’t have to be totally separate,” well, these are all good things, right?

Besides, the potential for “Yeethoven” to result in outrage, disagreement, slippage, disharmony and even misguided overconfidence sans apologies seems quite appropriate for the subject matter, no?

“The Great Music Series: Yeethoven“ takes place Saturday, April 16, at 7:30 p.m. The event is free, but tickets are required, available first-come first-serve starting at 6:00 p.m.