Violinist: Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition Begins August 16

Violinists from around the world arrived over the weekend in Shanghai, where 24 violinists ages 18 through 32 will begin competing Tuesday in the first-ever Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition, which is offering a record-breaking top prize of $100,000, to be awarded when the competition concludes on Sept. 2.

Violinists in the 2016 SISIVC, after a "bow draw" on Monday to determine First Round order.

Violinist.com

By Laurie Niles

Violinists from around the world arrived over the weekend in Shanghai, where 24 violinists ages 18 through 32 will begin competing Tuesday in the first-ever Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition, which is offering a record-breaking top prize of $100,000, to be awarded when the competition concludes on Sept. 2.

Watch for Violinist.com coverage from Shanghai, starting Aug. 24 from the semi-finals.

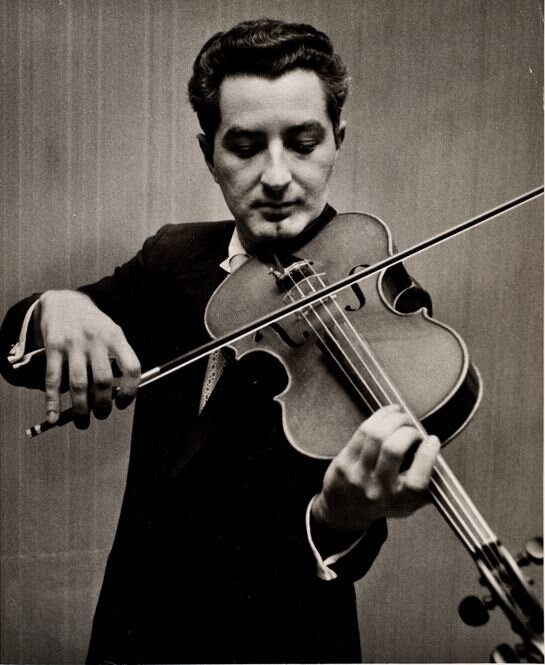

The competition was named after the famous American violinist Isaac Stern (1920-2001), who broke cultural ground when he traveled to China in 1979 -- a time when China-U.S. relations were tenuous at best. Stern gave concerts and also visited China’s Central Conservatory of Music and the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. The trip resulted in a documentary called From Mao to Mozart, which won an Academy Award in 1980 for Best Documentary Feature.

The competition, two years in the making, will take place at Shanghai Symphony Hall. The 24 competitors represent several countries, including China, Japan, South Korea, France, Germany and the United States. Nearly half of the competitors are from China, with three from the United States. Of the 21 competitors who are not listed as being from the United States, eight of have strong U.S. connections, having studied in the U.S. at places such as the Curtis Institute, The Juilliard School, New England Conservatory, Temple University's Boyer College, Bard College Conservatory and the Aspen Music Festival. One contestant from China is a member of the Oregon Symphony. For full bios of the competitors, click here. (Names of all competitors are listed at the bottom of this article).

Preliminary rounds take place Aug. 16-19, and performances will be available to view afterwards on the competition's YouTube channel. Here is a schedule.. Semi-finals and Finals will be live-streamed on SMG and LeTV -- we'll provide links as they become available.

After preliminaries, 18 competitors will be named semi-finalists. Semi-finalists are required to perform The Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto, which has achieved modern popularity after being written in 1959 by Chinese composers, He Zhanhao and Chen Gang, while they were students at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. Semi-finalists will also play Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 3 with a chamber orchestra (original cadenzas required), a sonata, and the first movement of piano trio by Schubert or Brahms. Competition officials report that all semi-final tickets were sold out within one week of ticketing -- I'd like to think this is a testament to the popularity of the violin in China!

Six finalists will go on to the Final Round, Sept. 1 and 2. Besides the record-breaking First Prize of $100,000 USD; other prizes include a Second Prize of $50,000, Third Prize $25,000 and Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Prizes $5,000 each. Another $10,000 will be awarded for the best performance of "The Butterfly Lovers" concerto; and a $10,000 Isaac Stern Human Spirit Award will go to a non-contestant "in any field and from any part of the world - who is deemed to have made an outstanding contribution to our understanding of humanity through the medium of music."

The competition also has promised winning competitors performance opportunities with various orchestras, including Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, China Philharmonic Orchestra, Guangzhou Symphony Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, and Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

Jury members for the competition are Zakhar Bron, David Cerone, Martin Engstroem, Daniel Heifetz, Emmanuel Hondré, Boris Kuschnir, Elmar Oliveira, David Stern, Maxim Vengerov, Jian Wang, Zhenshan Wan, Vera Tsu Weiling and Lina Yu.

Competitors in the 2016 Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition are:

- Takamori Arai, Japan

- Yu-Ting Chen, Taiwan, China

- Elvin Ganiyev, Azerbaijan

- Fangyue He, China

- Sirena Huang, United States

- Yiliang Jiang, China

- Jee Won Kim, South Korea

- Mayu Kishima, Japan

- Zeyu Victor Li, China

- Richard Lin, United States

- Ming Liu, China

- Kyung Ji Min, South Korea

- Raphaëlle Moreau, France

- Andrea Obiso, Italy

- Dongfang Ouyang, China

- Yoo Min Seo, South Korea

- Ji Won Song, South Korea

- Kristie Su, United States

- Stefan Tarara, Germany

- Xiao Wang, China

- Wendi Wang, China

- Jinru Zhang, China

- Yang Zhang, China

WQXR: Bite-Sized Bytes: Ray Lustig Composing in 15 Seconds

What would you do with 15 seconds? For composer Ray Lustig, it's the perfect amount of time to set up a low-stakes creative lab and ongoing audio-visual experiment. He explains below the inspiration behind his 15-second Instagram compositions, dubbed "composagrams," and how they feed his artistic growth.

WQXR's Q2 Music

What would you do with 15 seconds? For composer Ray Lustig, it's the perfect amount of time to set up a low-stakes creative lab and ongoing audio-visual experiment. He explains below the inspiration behind his 15-second Instagram compositions, dubbed "composagrams," and how they feed his artistic growth.

Last summer I started a new little creative habit: making tiny 15-second compositions with video, a new one, roughly every week, to post to my sleepy little Instagram account. I’d heard that Instagram, formerly dedicated to photos, had recently started hosting video posts, but only up to a 15-second max, and this constraint grabbed my interest. Was it possible to do anything musically meaningful in just 15 seconds? At first I wasn’t sure. Many of my favorite works — Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, and Steve Reich’s Drumming — are over an hour long.

I gave 15 seconds a try. And then another, and another. I started calling them "composagrams" and even started tagging them with the hashtag #composagram to encourage others to do it, too.

Then I started to realize that my little collection of composagrams was serving as a kind of creative lab for me. I was testing new things out, putting new spins on old things, dipping my toe in waters I might not have gotten to in my larger more visible projects, actually expanding my experimentation. Yet at the same I noticed I was following the evolution of my sound preferences with more focus, via these little bits of experimentation.

And now, 15 seconds seems to me kind of perfect. It’s too short to even give a listener time to become bored, yet it’s longer than a gesture, even longer than a phrase. It can be a sentence, a concise one, a to-the-point sentence. While it’s an actual public post of my music, it's low-stakes. If one turns out not so satisfying for me, well it’s only 15 seconds, and I can just start another one.

There's using social media creatively for self-promotion and dissemination of one’s work, but this is different. This is using it as an actual creation platform, music written just for the consumption style of the social media feed. And it's not simply an opportunistic niche. There's something to casting work into the public light regularly that helps you hear it differently, gives you that crucial new perspective on something we artists spend all our time so close to, our own work.

Composers out there, give it a try if you don't believe me. And use the hashtag #composagram so that people who see one and like it can check out a few more. Instagram changed its limit to 60 seconds, but that's an eternity in social media time, so discipline yourself to keep it to that perfect little 15-second window, that bite-size, to-the-point little sentence. If you can't decide what to do, do a bunch of them so you don't have to decide. Make it a habit that feeds your artistic growth. — Ray Lustig

Born in Tokyo and raised in Queens, N.Y., composer Raymond Lustig is deeply inspired by science, nature, and the mind. Also a published researcher in molecular biology, he studied cell division, the cell skeleton, and cell polarity at Columbia University and Massachusetts General Hospital before beginning his graduate studies in composition at Juilliard, where he completed his MM and DMA degrees.

Strings Artist Blog: Cellist Julian Schwarz Discusses Is Talent Inherited?

It is true, that there are moments in music when one cannot simply deny the existence of something special––something undeniable, and sometimes inexplicable. And there was a certain moment in [cellist, Julian Schwarz's] life when the case for inherited musicality made an extremely compelling case.

Strings Guest Blog

Julian Schwarz

Having been born into a multi-generational musical family, I was often told “it’s in your genes” or “it must run in the family.” This always struck me as odd, especially as a youngster, as I was spending hours in the practice room honing my craft. If it were all in my genes, why was I working so darn hard anyway? If we take this one step further, the whole idea of talent is a rather abstract idea in the first place. I recently sat on a jury for a competition in New Jersey when, after a particularly gifted student auditioned, a colleague on the jury said, “I always aim to dispel the notion that talent actually exists, but after hearing that, it is a hard angle to defend.” It is true, that there are moments in music when one cannot simply deny the existence of something special––something undeniable, and sometimes inexplicable. And there was a certain moment in my life when the case for inherited musicality made an extremely compelling case.

My maternal grandfather, Sol Greitzer, was a violinist born in the Bronx in 1925. After returning from his service in the United States Army, as a runner in the Battle of the Bulge in World War II, he found the high frequencies of the violin too piercing for his artillery sensitized hearing. He switched to the viola, and quickly ascended the ranks of the NBC Symphony and the New York Philharmonic. In 1972 he became the principal viola of the NY Phil under Pierre Boulez.

His premature passing in 1989 took him from this earth prior to my birth, and I neither had the chance to meet him nor to hear him play. As a young boy I was told frequently by family “he would have loved you,” which, though sentimental and sweet, made me yearn to have known him. This sentiment became stronger in the family as my deep love for the game of baseball grew (let’s go Mets)—as he was a fan of the game and always wished for a son among his three daughters.

My grandfather Sol passed before the age of instant recording, so very little evidence of his playing remains to this day. It was not until I was 17 that I heard even a note. By this time my musicianship had developed to a certain point, and my first string of concerto appearances had come to pass. My mother had received an old live radio broadcast of my grandfather playing the Stamitz Viola Concerto with the New York Philharmonic and Zubin Mehta on the podium. I was beyond excited to hear his tone, phrasing, and overall style. After putting the disc in my portable CD player, my sense of expectation built through the opening tutti. Every cadence raised my heart rate as I was ready to hear what I had been missing for years.

Finally, his warm, rich tone entered and I was taken aback. I started to cry. I could not believe my ears. His phrasing was elegant, his vibrato constant, his portamento tasteful yet old fashioned; this was the playing I always envisioned for myself. This was the playing that more closely resembled mine than any cellist or string player I had heard up to that point.

Without ever hearing him, without ever meeting him, and without ever feeling his presence, I had grown up to sound just like him––in every way. There were subtle differences, but the similarities were undeniable.

Who knows if musicianship is inherited, but at that moment I felt connected to a man I never knew, and so wished I had.

The Strad: Violinist Isaac Stern in China

Captured in the 1979 Academy Award-winning documentary From Mao to Mozart, Isaac Stern had a transformative effect on China's classical music scene - more than he ever knew. Today his legacy lives on with the launching of the Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition. Nancy Pellegrini talks to son David Stern and some of the film's stars about the 'Stern effect.'

The Strad

Excerpts from Violinist Isaac Stern in China

Captured in the 1979 Academy Award-winning documentary From Mao to Mozart, Isaac Stern had a transformative effect on China's classical music scene - more than he ever knew. Today his legacy lives on with the launching of the Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition. Nancy Pellegrini talks to son David Stern and some of the film's stars about the 'Stern effect.'

The year was 1979. Emerging from decades of isolation and political turmoil, China had just opened its door to the West, and legendary violinist Isaac Stern was hoping to peek inside. The result was the Academy Award-winning documentary From Mao to Mozart, which chronicles Stern's visit to music conservatoires in Beijing and Shanghai. This brilliant, touching film gave Westerners an insight into life behind the Bamboo Curtain, while igniting Chinese careers and changing music in China forever. The Stern family has continued its association with the country, but it is China that will never forget. August 2016 was the start of the inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition (SISIVC), which organisers hope will help to inspire and motivate a new generation of musicians.

Isaac Stern had long used his musicianship to build bridges and foster talent, touring the Soviet Union in 1951, helping save New York’s Carnegie Hall from destruction, and mentoring a host of promising young players including Itzhak Perlman, Yo-Yo Ma and Pinchas Zukerman. While some claimed his extra-musical efforts were hampering his own skills, music and humanity were, to him, simply extensions of each other. China opening up to the West was his next logical frontier.

However, when even US diplomat and close friend Henry Kissinger couldn't help him gain entrance, Stern had a strategically casual dinner with China's foreign minister, and an evening conversation became an official invitation. The film was also a product of family friends, but the Sterns insisted it be about China, not them. 'Even when I see it today, that's what impresses me; it was so unpretentious,' says David Stern, whose clear admiration for his father still resonates. 'It wasn't a grand master delivering the word. My father had lived a life that very few people can live, and all he wanted to do was share it.'

Wang is certain that Stern brought about a seismic change in China's music scene. 'He showed us, he told us, he demanded from us that music was all about expressing yourself,' he says. 'The content is more important than the presentation - and in those days in China, presentation was everything.' China had talented teachers, he recalls, but the general trend was to study the form and imitate the West. 'We did not have the confidence nor the tradition to say that music is only a tool to express yourself,' he recalls. 'Isaac Stern said "I don't care how you play, but you have to say something."'

Maybe even more than music, Stern was known for mentorship, which is why the family eventually allowed his name to be attached to Shanghai's newest competition. But they had concerns. 'This was not an easy birth because my father principally believed that music is not a competition,' says David Stern. In fact, Isaac had avoided the competition circuit and nurtured talent so that others could do the same. But times have changed. 'An Isaac Stern of today would not have the influence he did then; the music world was smaller, moved slower, had more patience,' he says. 'Today it is increasingly difficult for young musicians to get their chance.'

Launched by the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra (SSO) to discover talent and honour Stern's legacy in China, the SISIVC has been designed with Stern in mind. This means that, although virtuosity is rewarded, musicianship and development will come first. David Stern himself insisted on a chamber music round, and organisers will introduce the most promising candidates to top music agencies. The jurors' scores and comments will be released to the public, so that candidates can receive further feedback. And the SSO and principal sponsor China Pacific Insurance's musical outreach programme 'The Rhythm of Life' will allow competition laureates to give concerts with the orchestra at venues across the country. 'The programme is entrusting young musicians with enriching the life and culture of urban centres around the country,' says SO president and SISIVC executive president Fedina Zhou, 'fulfilling its core philosophy of bringing music to the ears of many, and turning "soloists" into "musicians".'

Tsu, who serves with Stern as jury co-chair, feels that Shanghai - and indeed China - is due for an international competition of this scope, and is already excited about the contestants' high level. Wang feels there is no better homage to Stern. 'He cultivated and propelled so many new careers; some of the greatest performers alive are performing because of him. There are only one or two in the history of music like that. We need to keep his legacy alive.' Li also sees overwhelming positives, and points out that when it comes to music in China, SSO music director Long Yu has the Midas touch. 'Everything he organises blossoms so much,' he says. 'With anyone else I would be sceptical, but with him I have confidence that this will be great.' He also says that while many competition winners disappear after a handful of concerts,' Yu's myriad orchestra connections will be a boon for the winners. 'This will build a concrete career for these young soloists.'

But the most important factor is to keep Isaac Stern's legacy, and the From Mao to Mozart spirits alive. 'My father was one of the few who managed to elevate everyone around him,' says David Stern, 'whether it was a conversation in a restaurant or playing a violin concerto.' And this will indeed be a family affair. The violinist's daughter Shira will be presenting the Isaac Stern Award, granted to the person in any field, from any country, who best uses music to improve society. His son, conductor Michael Stern, will conduct the orchestra for the final round, before working with Yo-Yo Ma on a 2017 youth festival in Guangzhou. David Stern has been conducting in China several times a year since 1999, when he led his father and other film alumni (including Wang and Tsu) in a 20th-anniversary From Mao to Mozart concert. Today he runs an annual Baroque festival in Shanghai and teaches vocal masterclasses. He repeatedly insists he is not following in his father's footsteps, saying, 'I just believe in it and I love doing it.'

But perhaps the best takeaway is Isaac Stern's address at the end of the film: 'If you do not think that music can say more than words, that there can be no life without music; if you do not believe these things, then don't be a musician.' Says David Stern of his father's advice. 'It's the strongest defence of arts I've ever heard.' Words to live by indeed.

Greensboro News and Record: Music review - Gerard Schwarz and Brahms highlight EMF Chamber concert

By Jackson Cooper

The communal feel of attending an EMF concert can be equated to the spirit of a Fourth of July barbecue. Enthusiastic grins and reconnecting with old friends is a common sight. The audience chatters like children in anticipation for the show they are about to witness.

This created an exciting buzz around the evening of chamber works presented by EMF faculty and guest artists as the final installment of the Monday chamber series, held Monday night at UNCG Recital Hall.

The evening opened with Mozart’s Oboe Quartet in F major, performed by soloist Katherine Young Steele on oboe and accompanied by violin, viola and cello. A welcoming start to the program, Mozart’s piece is a more traditional sounding chamber work. All four instrumentalists succeed in controlling Mozart’s sudden dynamic changes nicely. In multiple sections, they used slight tempo changes to heighten the expressiveness of the piece. Steele’s oboe playing was lyrical throughout, gracefully adding to a richly satisfying dialogue between the four musicians.

After the Mozart appetizer followed Boccherini’s Guitar Quintet performed with Jason Vieaux on guitar accompanied by viola, two violins and cello. Living in Madrid for most of his life, images of Spain sprung to mind in the opening moments of Boccherini’s piece. Vieaux played Boccherini’s shifts between accompanist and solo lines with grace and ease, controlling dynamics masterfully.

During the final movement, the aptly named “Fandango,” cellist Julian Schwarz provided aerobic and percussive playing that seemed to captivate the audience. He even took a short break during the piece to play on castanets, one of the two percussion instruments the program notes mention (the other, a sistrum rattle, was sadly absent from this performance). The inspired performing, with special shout-outs to Schwarz and Vieaux, brought the audience to its feet for three ovations.

Following intermission, EMF favorite Awadagin Pratt joined the faculty for a moving performance of Brahms Piano Quintet in F minor. Much darker and undulating in tone than other Brahms chamber works, the piece introduces in a musical idea which it riffs and rhapsodizes over the course of the opening movement, creating a dark tapestry of sound different from for instance, the playful Mozart from the first half. The tone of the first movement is one of uncertainty, creating a feeling of suspense as a listener.

The Andante section is a lighter detraction from the first movement, and Pratt and his cohorts made the shift in tones seamless to create a romantic intermezzo. A rousing Scherzo section followed, containing some ensemble glitches. Despite these, the climactic moments of exuberance were well captured by the players.

The Finale, a mirror to the first movement in contrasting tones, pushed the quintet into its most passionate playing, as if the musicians had been held back for three movements and now, they are able to let loose. Brahms’s sudden shifts in mood were thrilling to experience. By the time they reached the final chord, the audience did not seem to want it to be over. It makes you wish every Monday could be this inspiring.

The Strad: Review of Israeli Chamber Project's NYC Concert May 5, 2016

The Strad provides a glowing review of Israeli Chamber Project's concert at NYC's Merkin Concert Hall on May 5, 2016.

The Strad

Review by Leah Hollingsworth

The Israeli Chamber Project played with character and aplomb in this concert at Merkin Hall. The dense score of Weber's Clarinet Quintet was performed with a rich depth that may have seemed a mire overbearing but which conveyed a confident and charismatic energy.

André Caplet's Conte fantastique began with an arresting reading of Edgar Allan Poe's The Masque of the Red Death - on which the piece was based - by actor Michael Cumsty. A sinister entry by violist Dov Scheindlin and cellist Michal Korman gave way to a tumultuous and brilliantly executed performance by all members of the quintet (string quartet and harp). Complex rhythms and myriad extended techniques were well executed and embodied the disturbing and dramatic nature of the text effectively. The piece reached a frenetic climax that verged exhilaratingly on losing control. The ensemble playing was fantastic and harpist Sivan Magen was particularly vibrant.

Although by the end of Brahms's Piano Quintet the string players were obviously fatigued, their performance of this marvellous music was as passionate and heartfelt as the earlier works. Korman's introduction to the finale's theme was absolutely stunning - light but not trite, and played with an optimistic sound tinged with sadness and depth.

Violin Channel: Julian Schwarz Guest Blogs about Schoenfeld International String Competition

With the 2016 Schoenfeld International String Competition underway this week in Harbin, China, VC recently caught up with a number of former prize winners to get a better understanding of their time at the competition – and the career-changing opportunities the biennial event has presented. 2013 Cello Division 1st prize winner, Julian Schwarz guest blogs about his eventful experience:

With the 2016 Schoenfeld International String Competition underway this week in Harbin, China, VC recently caught up with a number of former prize winners to get a better understanding of their time at the competition – and the career-changing opportunities the biennial event has presented.

2013 Cello Division 1st prize winner, Julian Schwarz guest blogs about his eventful experience:

“In 2004 I had the great honor of performing in a masterclass given by the distinguished cellist Eleanor Schoenfeld. I had heard wonderful things about her teaching, and was eager for the opportunity. She was a very elegant woman. Her German accent was subtle yet intriguing, as was her graceful playing. Little did I know that nine years later her namesake competition would prove such an important part of my young career.

A week in August 2013 was the first installment of the inaugural Alice and Eleanor Schoenfeld International String Competition (then in Hong Kong, now in Harbin). Though I had made the effort to apply and officially enter the competition, I was reticent to make the trek. The timing was not ideal, as the competition was set to take place following my first summer as a faculty member at the Eastern Music Festival, which directly preceded a residency at the piano Sonoma Festival in California. I had the usual pre-competition thoughts and fears—what if I go all the way there and get cut in the first round? When will I find time to prepare the compulsory piece?

My response to these fears was to put off buying my plane tickets and focus on my work at hand. The days hurried by. The competition was right around the corner and I had neither began learning the required piece nor booked any travel or accommodation whatsoever. Decision time. I bought my tickets. I figured that I would somehow find a way to prepare the necessary repertoire if I had no choice but to step on that plane.

On the day of my flight to Hong Kong, I found myself in a state of palpable stress. I had yet to look at the commissioned piece. I told myself to focus on my concert that afternoon and worry about the competition on the way to the airport (I was catching a 1 am flight after a late afternoon chamber performance in Sonoma).

The flight was long, but allowed me to study the repertoire over my breakfast of seafood congee. It was my first time in Hong Kong, but I promised myself I would not let my desire to enjoy the town get in the way of my preparation. I checked into the hotel and started to practice. It turned out that nature had its own way of insuring my practice captivity—it was typhoon time. Yes, the whole city was filled with rivers of water, and I was confined to my hotel room by government order. All day I practiced. I played from morning till night, and sometimes with a practice mute at 4 am during bouts of jet lag.

During this period of practice madness I convinced myself that the only way to get over the guilt of having royally procrastinated learning the required piece, was to commit it to memory. How could the jury possibly think I had crammed learning a piece that I had memorized? This pursuit was aided by the competition’s 24-hour postponement of the first round.

The preliminary came and went in a flash. My bow hair limp, I performed my best and made it through my required piece unscathed. As I hadn’t heard back from the competition that evening, I figured my presence in any future rounds unlikely. When 2 am rolled around, I rolled around to my deafening hotel phone. I had advanced. The next round was in 8 hours.

Though the typhoon made scheduling slightly more compact, I can’t say I had any problem with it. In performance, it’s the best feeling to just get out there and do it. The more time you have to think the worse it gets. If you give your brain a chance to get anxious, it will get anxious. This is one of the reasons I adore afternoon concerts. You get up, have something to eat, and play your heart out. For an evening performance, you get up, worry, worry some more, and then play your heart out.

The next rounds happened in similar fashion to the first. Always a 2 am wake-up call with good news, and another performance right around the corner. The final call was to tell me I had won the first prize.

The prizewinners concert was the first moment the reality of my win started to sink in. It was my conversation with the eminent maestro Jorge Mester directly following the performance that made me the most excited. I was just onstage holding a big foam check in one hand and a human sized trophy in the other, but it was my very brief conversation with maestro Mester that gave me the biggest rush.

“Maestro Mester would like to see you now,” I was told by a competition employee.

I was caught off guard, but was eager to hear what he had to say—he was the jury chairman after all.

“Yes Julian,” he started, “I need you to be the principal cello of the Louisville Orchestra this season ok? Think about it ok? Here’s my information. Thanks.”

I could barely get a word in of appreciation before he had left. Wow, what an offer. And so soon after all of the incredible competition festivities.

I was still in school and, with great regret, had to turn down the offer, but this was just the beginning of a wonderful friendship and musical partnership with this great maestro. I played the opening week as principal cello in Louisville, as it was before school was set to begin. That week I was offered a solo engagement with the orchestra in a coming season. The next summer, I was called by the Orquesta Filarmonica de Boca del Rio in Mexico to perform as its first guest soloist. It was a newly created orchestra, with none other than the great maestro Jorge Mester as the Music Director.

Since the competition I have worked with maestro Mester in Boca del Rio, Veracruz, Louisville, and Mexico City, performing Dvorak, Elgar, and Shostakovich 1st Concertos. What a gift the competition gave me to play for this great conductor.

The year after the competition my solo engagements started to increase. Presenters and orchestras that had been considering me as a soloist for some time finally had the stamp of approval that only a prominent international competition can provide.

The most influential opportunities the Schoenfeld Competition awarded me came as a result of the important jury members and their desire to engage me in the future, but the monetary prizes were also useful in my career. The money I won was used to record the complete cello/piano works of Ernest Bloch for the Milken Archive, to make my debut recital recording with pianist Marika Bournaki (to be released later this year), and to buy a beautiful upright piano for my apartment in New York City. I was also awarded a fantastic German cello that I still own. It was quite the ordeal to figure out how to get two cellos back with me to the U.S. post-competition, but I am happy to say that the German instrument survived just fine in the hold!

I wish nothing but the best for the prizewinners of this year’s Schoenfeld Competition. There are fantastic opportunities for those who win, and for those who don’t, one must remember that being a musician is about getting out there and doing it. I love playing for people. I love playing wherever there is a public willing to listen. I played for large, appreciative audiences at the 2013 Schoenfeld Competition. That will always be enough.

-Julian”

Pablo Sáinz Villegas Performs in Sold-Out Tribute Concert for Placido Domingo

Pablo Sáinz Villegas was honored to be invited to perform at the historic tribute concert to the great and beloved Placido Domingo at the Santiago Bernabeu stadium in Madrid on June 29, 2016.

Pablo Sáinz Villegas on stage with Plácido Domingo in front of a sold-out stadium of 60,000.

Pablo Sáinz Villegas was honored to be invited to perform at the historic tribute concert, “Plácido en el Alma” (Placido in the Soul), for the great Plácido Domingo at the Santiago Bernabeu stadium in Madrid on June 29, 2016. The event was in honor of the beloved artist's 75th birthday. Proceeds from the concert were given to 38 sport schools of Real Madrid’s Foundation in Mexico.

The Guardian: Orchestral maneuvers in the park - classical festivals in stunning scenery

The hills of America’s most stunning national parks including Grand Teton will be alive this summer with the sound of music to celebrate the centenary of the National Park Service

Dawn in Grand Teton national park. Photo: Alamy

The Guardian

By Brian Wise

Visual artists have been so successful at capturing America’s national parks that some have served as valuable campaigners for wilderness conservation. Consider Albert Bierstadt’s huge landscape paintings of Yosemite or Ansel Adams’s famous photographs of Yellowstone. But composers have mostly refrained from portraying these natural wonders, perhaps hampered by music’s fundamentally abstract nature.

A few have tried, however, and more will do so in the coming months as the National Park Service celebrates its 100th anniversary.

In the 20th-century, Ferde Grofé was classical music’s greatest national parks advocate. His Grand Canyon Suite – inspired by a camping trip to Grand Canyon National Park in 1916 – depicts a painted desert, a pounding storm, and the clip-clop of a mule descending to the canyon floor. Grofé later portrayed other national parks, composing a Death Valley Suite in 1949 and a Yellowstone Suite (1960).

In 1972, French composer Olivier Messiaen, a synesthete and lover of birdsong, made an eight-day visit to Utah’s Bryce Canyon and neighboring national parks, which yielded Des Canyons aux Étoiles … (From the Canyons to the Stars …), a gaudily pictorial, 12-movement symphonic poem. More recently, Nico Muhly, on a commission from the Utah Symphony, composed Control: Five Landscapes for Orchestra (2015), also inspired by Utah’s national parks (and featured on a new recording).

A category apart is Stephen Lias, an American composer who has held a series of National Park Service residencies, living and working in Rocky Mountain, Glacier, Denali and Glacier Bay National Parks, among others. His music will be performed in centennial concerts in Washington DC on 23 and 25 August.

There’s another way that culture and national parks intersect: at a number of music festivals that take place near or on park grounds.

Grand Teton music festival (Grand Teton national park, Yellowstone national park)

When it comes to Rocky Mountain festivals, Aspen, and to a lesser degree, Vail, get most of the attention. But this fest, located in Teton Village, Wyoming, puts you within an alphorn’s call of Grand Teton national park, with its magnificent 13,000ft peaks. It’s also an hour’s drive from Yellowstone, with its hot springs and grazing bison. Headliners include violinist Joshua Bell performing the Four Seasons of Vivaldi and Piazzolla, cellist Johannes Moser (Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations), violinist Nicola Benedetti (the Korngold Violin Concerto) and up-and-comer Simone Porter (Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto). While programming leans on the tried and tested, the rugged surroundings can pull you out of your comfort zone.

4 July - 20 August, $10-$55, gtmf.org

Strings Artist Blog: Julian Schwarz on “Your Cello Sounds Great!”

The old Heifetz story goes that the master would be told frequently after concerts, “Maestro, your Stradivari sounds incredible.” In response, he would open up his case, bring his violin to his ear, shrug, and quip, “I don’t hear anything!” Though this comedic response has become a joke among many prominent soloists, the reality remains the same—there is a fundamental misunderstanding among musicians and music lovers alike as to what produces sound and, by extension, what is to be lauded.

The old Heifetz story goes that the master would be told frequently after concerts, “Maestro, your Stradivari sounds incredible.” In response, he would open up his case, bring his violin to his ear, shrug, and quip, “I don’t hear anything!” Though this comedic response has become a joke among many prominent soloists, the reality remains the same—there is a fundamental misunderstanding among musicians and music lovers alike as to what produces sound and, by extension, what is to be lauded.

Just as Heifetz implied, the sound of an instrument is created by the musician. Though a great instrument can give a skilled artist access to a wide color palate, that same instrument does not create colors by itself. There is no string playing equivalent to piano rolls . . . yet!

That said, I have grown to interpret the comment, “Your instrument sounds great,” to mean, “You make a great tone.” I assume this is the intention of the compliment—at least I hope it is. It’s always difficult for me to remind myself of this, however, especially in the moment. I recently performed a series of concerts, after which I received nice compliments—about things over which I had no control.

“Wow, the new shell in our hall made your cello project so well!”

“Wow, that is the loudest cello I have ever heard!”

“Wow, your cello is amazing!”

“Before the recent renovation of our hall, it was so difficult to hear cello soloists, but now I can hear every note!”

Of course, I try to see the best intention of each comment. Though each remark did not give me credit for my sound production, the end result was the same—I sounded loud.

The next day a review came out, which some would say was very good. Objectively, it was. Yet, after noticing the creativity in credit given the evening before, I could not help but notice a similar trend in the review. The critic commented that my cello produced wonderful colors and sounds in the concerto, and that the cello podium on which I sat projected my sound to a great extent.

Now, the cello podium was responsible for my projecting tone.

I was puzzled. I was not upset that the cello podium received undue credit, but I was confused as to what the writer thought my involvement was (if any) in the performance. If I neither made the sound nor the color, what did I do? Why has this become a popular way of saying “It sounded good” or “You have a nice sound”?

In this way I am envious of pianists. It seems ridiculous, as they have the hardest job in the industry (having to change instruments for every performance and become one with a new tool every time, always at the mercy of a piano technician to achieve the ideal tuning and action, and often without the ability to warm up on the instrument prior to a performance), but a pianist will rarely be told that his or her piano has a nice sound. Why? Because—with a few exceptions like Cliburn and Zimmerman—it is not their own piano. And every pianist who plays on that particular instrument has a different sound.

This side of the equation confuses me even more. A piano is merely a series of buttons. If I press the button and you press the button, the same sound should come out, right? And yet this could not be further from the truth. As many concertgoers and musicians notice, the sound and range of color and dynamics on a piano differs greatly, depending on who is playing.

On a stringed instrument, the variables seem much greater. A stringed instrumentalist’s sound, through the use of the bow, can vary to an even greater extent through weight, speed, sound point, strength, and one’s ear. The sound desired by a performer is incredibly subjective, and satisfaction with a particular sound at a particular time differs greatly from player to player. It is as much what you do to produce a sound as what you desire the sound to be like at its core.

Often a great pianist will receive the comment, “Wow, this piano has never sounded like that!” For a string player, it is very rare that an audience member would hear the same exact instrument played by two different players.

I first realized the great range of sound from player to player as a young student. I was attending a small chamber festival when my teacher took my cello for a demonstration. I did not recognize the sound. My jaw dropped. How was it possible that my cello sounded so different? It might have been my physical position in listening (an instrument always sounds different from a distance than under one’s own ear), but this was too great a disparity to attribute to my orientation.

I was stunned. Since then I have always been curious to hear other cellists play my instrument. There are great lessons to be learned in regard to one’s own sound, and the sound others produce naturally.

And as far as sound production is concerned: Yes, it is building up muscles. Yes, it is what is in the ear. Yes, it is partially to do with the greatness of an instrument. But guys, give us string players some credit once in a while, would ya?

For more from Julian Schwarz, read his other Strings exclusive blogs: “I Play the Cello. Should my Teacher?” and “Destiny—Tied with a Bow.”