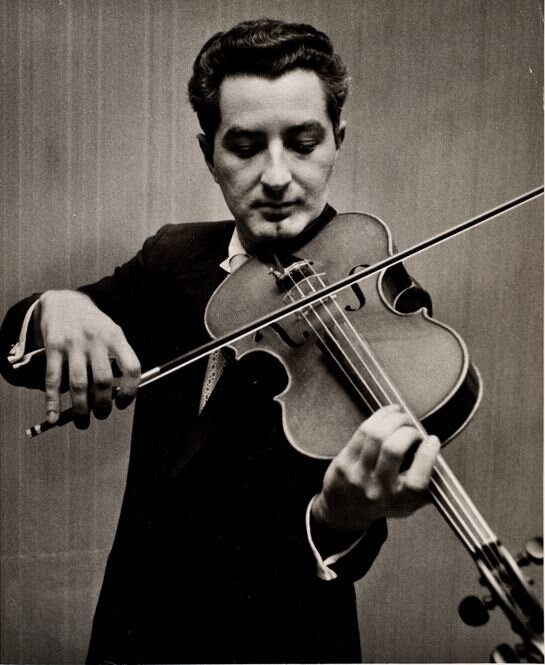

New Zealand Herald: Brief encounter - violinist Anne Akiko Meyers

Violinist Anne Akiko Meyers joins the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra for its Bold Worlds concert at the Great Hall, Auckland Town Hall on Friday, October 7.

Photo: Molina Visuals

You describe yourself as a modern classical musician - why is this an important definition for you?

I think it is important for performers to embrace technology to connect with today's audience. In addition to traditional concerto, recitals, chamber music and recordings, I reach a wider fan base by collaborating with a diverse group of musicians (including Wynton Marsalis, Il Divo, Michael Bolton, Ryuichi Sakamoto and Isao Tomita), embracing technology and social media. I also love supporting and commissioning composers to expand the violin literature. All these diverse musical ideas make me a much better musician.

Mason Bates Violin Concerto was composed for you - how does it feel to have a concerto composed especially for you?

Working closely with living composers always gives me a greater understanding of music from prior periods and makes me ask questions. Was it a muse or situation that inspired the composer to create a work that lives on for generations? I don't really think of the concerto as written for me, it's more a piece for the world. Over time, any great music needs to attract lots of performers who add the piece to their repertoire.

It's about a pre-historic dinosaur taking flight - were you a big dinosaur fan as a kid as so many young ones are?

There are many descriptive sound effects in the concerto; one where I am supposed to be the actual dinosaur trudging through swampy lakebeds with a sensual quality - that takes an active imagination! My children and their cousins love dinosaurs - it makes you always aware that humankind came from a very prehistoric place. Mason Bates, the composer, also has young children, and I think they are huge dinosaur fans.

If you could travel back in time to any concert, meet any composer - who would it be and why?

I think this would have to be Beethoven conducting his Symphony No.9. It's impossible to imagine that he composed that stone cold deaf.

What's the greatest threat to the future of classical music?

I think classical music has a wider audience than ever before due to technology. I am shocked to see videos I have put on YouTube have been played millions of times. My family and I "attend" performances of the Berlin Philharmonic and Detroit Symphony Orchestra streamed into your home. This is amazing and incredible and will build the audience in younger generations. I wish I had that kind of access to recordings when I was in my 20s!

What makes you want to work with the NZ Symphony Orchestra?

I am super excited to see and experience New Zealand for the first time. My dad actually motorcycled around the country and sent photos of places I thought only existed in heaven. It will also be the first time I work with Fawzi Haimor [conductor] and the orchestra and it will be so much fun to bring Mason Bates' violin concerto to life together.

Why is this work important - and why should people want to come and see/hear it?

Mason Bates is a dynamic and extremely popular young American composer who is composer-in-residence with the National Symphony at the Kennedy Center and was also composer-in-residence with the Chicago Symphony. A leading composer of his generation, his music is inventive, colourful and highly expressive, not to mention incredibly challenging. Audiences always clamour for more and I am thrilled to bring his first violin concerto to New Zealand!

• Violinist Anne Akiko Meyers joins the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra for its Bold Worlds concert at the Great Hall, Auckland Town Hall on Friday, October 7.

New York Concert Artists (NYCA) Accepting Applications for 2017 Worldwide Debut Auditions for Pianists and Violinists

Learn more about applying to the New York Concert Artists 2017 Worldwide Debut Audition. Application deadline is December 1, 2016.

Learn more about applying to the New York Concert Artists 2017 Worldwide Debut Audition, with prizes including Berliner Philharmonie + Carnegie Hall Debut Recitals, performance with Fairbanks Symphony, CD recording with Steinway & Sons Label, and more by clicking here. Application deadline is December 1, 2016.

Violinist: Anne Akiko Meyers releases 'Fantasia,' a last violin work by Einojuhani Rautavaara

The work Anne Akiko Meyers commissioned, called "Fantasia," was among the last pieces Einojuhani Rautavaara wrote. She recorded it in May with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Kristjan Järvi. Due to his recent death, she has made it available as a single on Amazon. It will be the title track on her upcoming album Fantasia: The Fantasy Album, to be released in spring 2017.

Violinist

By Laurie Niles

Anne Akiko Meyers and Einojuhani Rautavaara

Back in the 1990s Anne Akiko Meyers discovered a recording that stopped her in her tracks: Cantus Arcticus, by the Finnish composer Einojuhani Rautavaara.

"I was always flipping through CDs and sheet music at stores, trying to discover new works that were under the radar," Meyers told me last week over the phone. "That's how I came across the 'Concerto for Birds and Orchestra.' I was blown away by the sheer beauty of the music, and the way Rautavaara incorporated nature into a symphony. He actually went into a preserve and recorded birds chirping and singing, and that became an organic part of music. I listened to the recording many, many times on repeat."

The more she explored Rautavaara's works, the more she loved the music.

"I'm a lifelong fan," she said. "I've always been very enamored with these mystical, mythical composers like Arvo Pärt and Rautavaara."

In fact, last year she worked with Arvo Pärt to record his Passacaglia -- it made her think once again about Rautavaara. Might he like to compose a piece for her?

"It was always a dream of mine," she said. "I wondered, what is he up to, these days? I sent an e-mail to (his publisher) Boosey and Hawkes. You can risk getting a 'No' from a composer; it's always worth asking. I've commissioned many composers recently, and found that timing is crucial." The list of composers that Meyers has worked with and commissioned works from is long, and includes Mason Bates, Jakub Ciupinski, John Corigliano, Jennifer Higdon, Samuel Jones, Wynton Marsalis Somei Satoh, and Joseph Schwantner.

"I've become more tenacious about it," she said. Her tenacity paid off: "Immediately I got the response: 'He would love to write something for you. How long of a piece would you like?'"

Rautavaara had already written a violin concerto, "so I thought, what would pique his curiosity and be stylistically up his alley? That's when I came up with the idea of a 15-minute fantasy," Meyers said. "He sent me the music at the end of the summer, handwritten on manuscript paper. I was just smitten. Immediately I could sense overtones of Cantus Arcticus, and also his Symphony No. 7, the Angel of Light."

That was in 2015. If she'd waited any longer, their collaboration may never have happened; Rautavaara died in July 2016, at the age of 87. The work Meyers commissioned, called "Fantasia," was among the last pieces he wrote. She recorded it in May with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Kristjan Järvi. Due to his recent death, she has made it available as a single on Amazon. It will be the title track on her upcoming album Fantasia: The Fantasy Album, to be released in spring 2017.

Though Rautavaara did not live to hear the work in concert, he heard Meyers play it in person. After sending her the work, "he invited me to come to Helsinki," Meyers said. "I was so excited to go. I flew out in December 2015 and played the piece for him.

The second I finished, he turned to me, smiled so brightly and said, 'Wow, did I write some beautiful, beautiful music!' (She laughs) I thought that was the sweetest thing ever! Because it really is so deeply spiritual, poetic and beautiful."

"We played it again, and I expected him to say, 'Oh, this note, I'm not so sure...' I was also nervous about the bowings that I had changed, because his bowings were very specifically marked," she said. "The bowings really change the direction and meaning of the phrases."

Rautavaara liked it, though. "He said immediately, 'I love what you did, I don't have much confidence in myself with markings, especially bowings. I think you really brought out the phrasing to make it sing as much as possible, so let's use all your bowings.' That was that! No dynamic changes, no note changes, nothing," Meyers said. He knew what he wanted.

Though his health may have been in decline, Rautavaara was at the height of his composing powers, she said. "There's just so much experience and a rich, vast wisdom that he had, right in his fingertips. I think it's one of the most beautiful pieces ever composed."

WQXR: Ethan Hawke Cameos in Pianist Bruce Levingston's Philip Glass Survey

Bruce Levingston, no stranger to the music of Philip Glass, has finally issued an in-depth, two-disc survey of Glass's piano music, and the result is a surprisingly passionate and spontaneous portrait of the composer. Dreaming Awake (Sono Luminus) is a boldly individual approach to the keyboard works of an American master.

'Bruce Levingston: Philip Glass | Dreaming Awake' (Orange Mountain Music)

WQXR

By Daniel Stephen Johnson

Bruce Levingston, no stranger to the music of Philip Glass, has finally issued an in-depth, two-disc survey of Glass's piano music, and the result is a surprisingly passionate and spontaneous portrait of the composer. Dreaming Awake (Sono Luminus) is a boldly individual approach to the keyboard works of an American master.

Interpreting the piano music of Glass offers a unique dilemma to the pianist. The construction of the music is often severe and mathematical, the materials lucid to the point of total transparency in order to better showcase the clockwork operation of the rhythms. Instead of plunging forward through a series of contrasting episodes, the music coolly repeats its cadences as if displaying itself in a mirror, allowing the listener to examine the same material from multiple angles.

But at the same time, the harmonic language of the music is undeniably steeped in affect. While the music's transparency and poise pull back towards restraint, the substance of those cadences push forward into warm-hearted sentiment. Should the pianist treat the score like a strict MIDI grid, metronomically obeying every rhythm in order to heighten the transparency of the music? Or should the performer take a cue from those ecstatic harmonies?

From the almost impulsive opening of this record, those first few notes of Glass's magnificently subtle Etude No. 2, it becomes clear that Levingston has given himself over to feeling. This is Glass the Romantic.

In addition to a generous helping of the Etudes, arguably the composer's most substantial solo works, Levingston also offers the rarer title track, his own arrangement of Glass's tuneful film music for The Illusionist, and the earlier Allen Ginsberg hymn Wichita Vortex Sutra.

Even Levingston's stellar choice of collaborator fits the bill. Instead of sampling Ginsberg's own delightfully idiosyncratic reading of "Wichita," Levingston recruits thespian Ethan Hawke, Hollywood's Gen-X embodiment of Romanticism, and Hawke's breathless delivery is absolutely of a piece with the almost cinematic heroics of Levingston's vision for these pathbreaking works.

The New York Times: Shanghai Violin Competition Celebrates Isaac Stern’s Legacy in China

The inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition concluded on Friday after nearly three weeks of intensive performances by 24 young violinists from around the world. Mayu Kishima of Japan was awarded first place, taking home the grand prize of $100,000, the largest single award for an international violin competition.

The Japanese violinist Mayu Kishima was awarded the first prize at the inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition on Friday. Credit: Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition

The New York Times

By Amy Qin

More than 35 years after the violinist Isaac Stern made a groundbreaking visit to China, his legacy there lives on.

The inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition concluded on Friday after nearly three weeks of intensive performances by 24 young violinists from around the world. Mayu Kishima of Japan was awarded first place, taking home the grand prize of $100,000, the largest single award for an international violin competition.

“We were looking for the kind of spark and commitment to music that our father would have embraced,” David Stern, co-chairman of the jury committee, said in a telephone interview from Shanghai.

That Isaac Stern, who died in 2001, now has a competition bearing his name is somewhat ironic given his aversion to such events.

So when the conductor Yu Long, a towering figure in classical music in China, raised the idea of holding a competition about two and a half years ago, “it was not the easiest idea for the three of us to approach,” Mr. Stern said, referring to his brother, Michael, and his sister, Shira. “Our father did everything he could to mentor young musicians in order to avoid competitions.”

Isaac Stern’s dedication to training young musicians was perhaps most vividly captured in the 1979 documentary “From Mao to Mozart: Isaac Stern in China.” The film, which won an Academy Award for best documentary feature, chronicled Mr. Stern’s two-week trip to China for a series of concerts and master classes.

That visit, which came just as China was emerging from decades of self-imposed isolation and political tumult, is credited with having influenced a generation of young Chinese musicians, including Mr. Yu, who recalled sitting in the audience as a teenager during one of Mr. Stern’s performances in Shanghai.

“During the Cultural Revolution, we didn’t have many opportunities to play Western music,” Mr. Yu, now conductor of a number of ensembles including the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, said in a telephone interview. “Then, in that moment in 1979 when Maestro Stern came, we suddenly felt the difference in how we could understand music.”

Since 1979, classical music in China has grown tremendously, with gleaming concert halls being built around the country and some 40 million young Chinese studying the violin or the piano.

Still, Mr. Yu said, “The problem in China, and Asia more broadly, is that the players are more concerned about technical issues.”

So when it came to this new project, both the Stern family and Mr. Yu agreed that they wanted to make a more comprehensive competition that would reward musicians not just for technical ability, but also for all-around dedication to music.

After two years of discussions and planning, the Stern family and the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra came up with a competition structure that David Stern said his father, even with his distaste for competitions, probably would have approved. This meant including elements that were important to Isaac Stern, like chamber music and Chinese music.

For example, contestants in the semifinal round were required to perform two concertos: “The Butterfly Lovers,” a popular Chinese concerto composed in 1959 by He Zhanhao and Chen Gang, and Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 3 with a chamber orchestra (with original improvisation during the cadenza section). They also had to play a violin sonata, as well as the first movement of piano trio by Schubert or Brahms.

The 24 contestants represented several countries, including China, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea and the United States. In addition to the prize money, Ms. Kishima will also receive performance contracts with several international symphony orchestras.

Sergei Dogadin of Russia was awarded the second prize of $50,000, and Sirena Huang of the United States took home the third prize of $25,000. The violinists Zakhar Bron of Russia and Boris Kuschnir of Austria were among the 13 who sat on the jury.

The competition also presented an Isaac Stern Human Spirit Award of $10,000 each to two noncontestants: One, to Wu Taoxiang and Du Zhengquan, who founded the Einstein Orchestra, a middle-school ensemble in China, and the other to Negin Khpalwak, who directs an orchestra for women in Afghanistan, for “their outstanding contribution to our understanding of humanity through the medium of music.”

Most of the funding for the competition, which will be held every two years, came from corporate sponsors, according to Fedina Zhou, president of the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra. The symphony has been expanding in recent years, forging a long-term partnership with the New York Philharmonic and, in 2014, unveiling a new hall where the competition was held.

For many musicians and music lovers in China, the competition represents further validation that China is well on its way to becoming a heavyweight player in the classical music world.

“At last the Chinese people finally have an internationally recognized competition of their own,” said Rudolph Tang, a writer and expert in Shanghai on the classical music industry in China. “It has everything that a top competition should have, like a top jury, great organization, and high prize money.”

“It is like a dream come true,” he added.

The Strad: Shanghai Isaac Stern Violin Competition reveals scores of eliminated quarter-finalists

The inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition has released the scores of the candidates who have failed to make it through to the semi-finals. The violinists are competing for a top prize of $100,000 from 14 August to 2 September 2016.

The Strad

The inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition has released the scores of the candidates who have failed to make it through to the semi-finals.

The move reflects the competition’s commitment to transparency – the scores of all eleven judges (pictured) are revealed, in addition to their vote of ‘yes’ or ‘no’, indicating whether or not they believe the violinist should progress to the next round. The competition intends to release all candidates’ scores as they are eliminated, and of the winners following the final.

Click on the link below to read the latest results in detail:

Last week, the contest named the 18 candidates selected to progress to the semi-finals, taking place from tomorrow 23 August until 29 August. The violinists, aged between 18 and 32, are competing for an impressive grand prize of $100,000.

This year’s jury includes Zakhar Bron, Boris Kuschnir and Maxim Vengerov, in addition to Chinese violin professors Zhenshan Wang and Lina Yu, and co-chairs – conductor and son of Isaac Stern, David Stern, and Professor Vera Tsu Weiling.

In addition to six core prizes – including a second prize of $50,000 and a third prize of $25,000 – there will be two special awards for Best Performance of a Chinese Work and the Isaac Stern Award – given to ‘an individual who is deemed to have made an outstanding contribution to our understanding of humanity through the medium of music’.

For full details visit the SISIVC website.

Gramophone: Anne Akiko Meyers presents an exclusive first listen to Rautavaara's Fantasia

Last December Anne Akiko Meyers travelled to Finland to play Fantasia for Violin and Orchestra, written by the great composer, Einojuhani Rautavaara, which she will be premiering with Michael Stern and the Kansas City Symphony this upcoming season. Sadly with Rautavaara’s recent death, this will be a posthumous world premiere.

Gramophone

Last December I travelled to Finland to play Fantasia for Violin and Orchestra, written by the great composer, Einojuhani Rautavaara, which I will be premiering with Michael Stern and the Kansas City Symphony this upcoming season. Sadly with Rautavaara’s recent death, this will be a posthumous world premiere.

Rautavaara was a legendary Finnish composer who wrote eight symphonies, 14 concertos, and numerous other works for chamber ensembles and choir. He was a protégé of Sibelius, active until age 87, and was best known for writing Symphony No 7, Angel of Lightand the beautifully haunting work, Cantus Arcticus: concerto for birds and orchestra, a piece that took my breath away the first time I heard it.

In my early twenties, I regularly went to record and sheet-music stores, looking through items one at a time in the hope of discovering music that would make the hairs on my neck stand up. It was then I first discovered Rautavaara’s music, and for years, dreamed of commissioning him to compose more music for violin. In 2014, I inquired if Rautavaara, with the wonderful support of Boosey & Hawkes, would be interested in writing a fantasy for violin and orchestra. I was beyond elated when he responded that indeed he would and worked quickly. I received a handwritten draft of the score in the fall of last year, and breathlessly ran to my music studio to play through it.

I think there are similar qualities to the Angel of Light and Cantus Arcticus and Rautavaara’s signature soulful sound permeates throughout the piece, with fluid harmonies and deep moods -much like flowing large movements of water and majestic scenes from nature.

In December, I flew to Helsinki to meet Rautavaara and perform the work for him. We met at the apartment he shared with his wife, and the apartment was flooded with a special light that only seems to exist at the edge of the earth, overlooking the sea. He stood with a walker and was incredibly gentle and kind. Smiling and laughing, we spoke about how Sibelius liked the fact that Rautavaara owned an automobile, as well as his time in New York, studying at the Juilliard School where I also went to school.

After I played Fantasia, he looked at me and repeatedly said, 'I wrote such beautiful music!' We all laughed and agreed. He apologized for what he felt were his lazy bow markings and was so happy that I took the liberty to change the bowings to punctuate the phrasing the way I thought would bring his poetry out best. I was amazed that he made no changes to any notes or dynamics. Everything was in place just the way he wrote it.

Fantasia is transcendent and has the feeling of an elegy with a very personal reflective mood. Rautavaara’s music will live on forever and I thank him from the bottom of my heart for writing a masterpiece that makes me cry every time I listen to it.

Listen to an exclusive preview of Anne Akiko Meyers performing Rautavaara's Fantasia for Violin and Orchestra with the Philharmonia Orchestra and conductor Kristjan Järvi below:

Violinist: Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition Begins August 16

Violinists from around the world arrived over the weekend in Shanghai, where 24 violinists ages 18 through 32 will begin competing Tuesday in the first-ever Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition, which is offering a record-breaking top prize of $100,000, to be awarded when the competition concludes on Sept. 2.

Violinists in the 2016 SISIVC, after a "bow draw" on Monday to determine First Round order.

Violinist.com

By Laurie Niles

Violinists from around the world arrived over the weekend in Shanghai, where 24 violinists ages 18 through 32 will begin competing Tuesday in the first-ever Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition, which is offering a record-breaking top prize of $100,000, to be awarded when the competition concludes on Sept. 2.

Watch for Violinist.com coverage from Shanghai, starting Aug. 24 from the semi-finals.

The competition was named after the famous American violinist Isaac Stern (1920-2001), who broke cultural ground when he traveled to China in 1979 -- a time when China-U.S. relations were tenuous at best. Stern gave concerts and also visited China’s Central Conservatory of Music and the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. The trip resulted in a documentary called From Mao to Mozart, which won an Academy Award in 1980 for Best Documentary Feature.

The competition, two years in the making, will take place at Shanghai Symphony Hall. The 24 competitors represent several countries, including China, Japan, South Korea, France, Germany and the United States. Nearly half of the competitors are from China, with three from the United States. Of the 21 competitors who are not listed as being from the United States, eight of have strong U.S. connections, having studied in the U.S. at places such as the Curtis Institute, The Juilliard School, New England Conservatory, Temple University's Boyer College, Bard College Conservatory and the Aspen Music Festival. One contestant from China is a member of the Oregon Symphony. For full bios of the competitors, click here. (Names of all competitors are listed at the bottom of this article).

Preliminary rounds take place Aug. 16-19, and performances will be available to view afterwards on the competition's YouTube channel. Here is a schedule.. Semi-finals and Finals will be live-streamed on SMG and LeTV -- we'll provide links as they become available.

After preliminaries, 18 competitors will be named semi-finalists. Semi-finalists are required to perform The Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto, which has achieved modern popularity after being written in 1959 by Chinese composers, He Zhanhao and Chen Gang, while they were students at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. Semi-finalists will also play Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 3 with a chamber orchestra (original cadenzas required), a sonata, and the first movement of piano trio by Schubert or Brahms. Competition officials report that all semi-final tickets were sold out within one week of ticketing -- I'd like to think this is a testament to the popularity of the violin in China!

Six finalists will go on to the Final Round, Sept. 1 and 2. Besides the record-breaking First Prize of $100,000 USD; other prizes include a Second Prize of $50,000, Third Prize $25,000 and Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Prizes $5,000 each. Another $10,000 will be awarded for the best performance of "The Butterfly Lovers" concerto; and a $10,000 Isaac Stern Human Spirit Award will go to a non-contestant "in any field and from any part of the world - who is deemed to have made an outstanding contribution to our understanding of humanity through the medium of music."

The competition also has promised winning competitors performance opportunities with various orchestras, including Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, China Philharmonic Orchestra, Guangzhou Symphony Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, and Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

Jury members for the competition are Zakhar Bron, David Cerone, Martin Engstroem, Daniel Heifetz, Emmanuel Hondré, Boris Kuschnir, Elmar Oliveira, David Stern, Maxim Vengerov, Jian Wang, Zhenshan Wan, Vera Tsu Weiling and Lina Yu.

Competitors in the 2016 Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition are:

- Takamori Arai, Japan

- Yu-Ting Chen, Taiwan, China

- Elvin Ganiyev, Azerbaijan

- Fangyue He, China

- Sirena Huang, United States

- Yiliang Jiang, China

- Jee Won Kim, South Korea

- Mayu Kishima, Japan

- Zeyu Victor Li, China

- Richard Lin, United States

- Ming Liu, China

- Kyung Ji Min, South Korea

- Raphaëlle Moreau, France

- Andrea Obiso, Italy

- Dongfang Ouyang, China

- Yoo Min Seo, South Korea

- Ji Won Song, South Korea

- Kristie Su, United States

- Stefan Tarara, Germany

- Xiao Wang, China

- Wendi Wang, China

- Jinru Zhang, China

- Yang Zhang, China

WQXR: Bite-Sized Bytes: Ray Lustig Composing in 15 Seconds

What would you do with 15 seconds? For composer Ray Lustig, it's the perfect amount of time to set up a low-stakes creative lab and ongoing audio-visual experiment. He explains below the inspiration behind his 15-second Instagram compositions, dubbed "composagrams," and how they feed his artistic growth.

WQXR's Q2 Music

What would you do with 15 seconds? For composer Ray Lustig, it's the perfect amount of time to set up a low-stakes creative lab and ongoing audio-visual experiment. He explains below the inspiration behind his 15-second Instagram compositions, dubbed "composagrams," and how they feed his artistic growth.

Last summer I started a new little creative habit: making tiny 15-second compositions with video, a new one, roughly every week, to post to my sleepy little Instagram account. I’d heard that Instagram, formerly dedicated to photos, had recently started hosting video posts, but only up to a 15-second max, and this constraint grabbed my interest. Was it possible to do anything musically meaningful in just 15 seconds? At first I wasn’t sure. Many of my favorite works — Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, and Steve Reich’s Drumming — are over an hour long.

I gave 15 seconds a try. And then another, and another. I started calling them "composagrams" and even started tagging them with the hashtag #composagram to encourage others to do it, too.

Then I started to realize that my little collection of composagrams was serving as a kind of creative lab for me. I was testing new things out, putting new spins on old things, dipping my toe in waters I might not have gotten to in my larger more visible projects, actually expanding my experimentation. Yet at the same I noticed I was following the evolution of my sound preferences with more focus, via these little bits of experimentation.

And now, 15 seconds seems to me kind of perfect. It’s too short to even give a listener time to become bored, yet it’s longer than a gesture, even longer than a phrase. It can be a sentence, a concise one, a to-the-point sentence. While it’s an actual public post of my music, it's low-stakes. If one turns out not so satisfying for me, well it’s only 15 seconds, and I can just start another one.

There's using social media creatively for self-promotion and dissemination of one’s work, but this is different. This is using it as an actual creation platform, music written just for the consumption style of the social media feed. And it's not simply an opportunistic niche. There's something to casting work into the public light regularly that helps you hear it differently, gives you that crucial new perspective on something we artists spend all our time so close to, our own work.

Composers out there, give it a try if you don't believe me. And use the hashtag #composagram so that people who see one and like it can check out a few more. Instagram changed its limit to 60 seconds, but that's an eternity in social media time, so discipline yourself to keep it to that perfect little 15-second window, that bite-size, to-the-point little sentence. If you can't decide what to do, do a bunch of them so you don't have to decide. Make it a habit that feeds your artistic growth. — Ray Lustig

Born in Tokyo and raised in Queens, N.Y., composer Raymond Lustig is deeply inspired by science, nature, and the mind. Also a published researcher in molecular biology, he studied cell division, the cell skeleton, and cell polarity at Columbia University and Massachusetts General Hospital before beginning his graduate studies in composition at Juilliard, where he completed his MM and DMA degrees.

Strings Artist Blog: Cellist Julian Schwarz Discusses Is Talent Inherited?

It is true, that there are moments in music when one cannot simply deny the existence of something special––something undeniable, and sometimes inexplicable. And there was a certain moment in [cellist, Julian Schwarz's] life when the case for inherited musicality made an extremely compelling case.

Strings Guest Blog

Julian Schwarz

Having been born into a multi-generational musical family, I was often told “it’s in your genes” or “it must run in the family.” This always struck me as odd, especially as a youngster, as I was spending hours in the practice room honing my craft. If it were all in my genes, why was I working so darn hard anyway? If we take this one step further, the whole idea of talent is a rather abstract idea in the first place. I recently sat on a jury for a competition in New Jersey when, after a particularly gifted student auditioned, a colleague on the jury said, “I always aim to dispel the notion that talent actually exists, but after hearing that, it is a hard angle to defend.” It is true, that there are moments in music when one cannot simply deny the existence of something special––something undeniable, and sometimes inexplicable. And there was a certain moment in my life when the case for inherited musicality made an extremely compelling case.

My maternal grandfather, Sol Greitzer, was a violinist born in the Bronx in 1925. After returning from his service in the United States Army, as a runner in the Battle of the Bulge in World War II, he found the high frequencies of the violin too piercing for his artillery sensitized hearing. He switched to the viola, and quickly ascended the ranks of the NBC Symphony and the New York Philharmonic. In 1972 he became the principal viola of the NY Phil under Pierre Boulez.

His premature passing in 1989 took him from this earth prior to my birth, and I neither had the chance to meet him nor to hear him play. As a young boy I was told frequently by family “he would have loved you,” which, though sentimental and sweet, made me yearn to have known him. This sentiment became stronger in the family as my deep love for the game of baseball grew (let’s go Mets)—as he was a fan of the game and always wished for a son among his three daughters.

My grandfather Sol passed before the age of instant recording, so very little evidence of his playing remains to this day. It was not until I was 17 that I heard even a note. By this time my musicianship had developed to a certain point, and my first string of concerto appearances had come to pass. My mother had received an old live radio broadcast of my grandfather playing the Stamitz Viola Concerto with the New York Philharmonic and Zubin Mehta on the podium. I was beyond excited to hear his tone, phrasing, and overall style. After putting the disc in my portable CD player, my sense of expectation built through the opening tutti. Every cadence raised my heart rate as I was ready to hear what I had been missing for years.

Finally, his warm, rich tone entered and I was taken aback. I started to cry. I could not believe my ears. His phrasing was elegant, his vibrato constant, his portamento tasteful yet old fashioned; this was the playing I always envisioned for myself. This was the playing that more closely resembled mine than any cellist or string player I had heard up to that point.

Without ever hearing him, without ever meeting him, and without ever feeling his presence, I had grown up to sound just like him––in every way. There were subtle differences, but the similarities were undeniable.

Who knows if musicianship is inherited, but at that moment I felt connected to a man I never knew, and so wished I had.