WQXR: Ethan Hawke Cameos in Pianist Bruce Levingston's Philip Glass Survey

Bruce Levingston, no stranger to the music of Philip Glass, has finally issued an in-depth, two-disc survey of Glass's piano music, and the result is a surprisingly passionate and spontaneous portrait of the composer. Dreaming Awake (Sono Luminus) is a boldly individual approach to the keyboard works of an American master.

'Bruce Levingston: Philip Glass | Dreaming Awake' (Orange Mountain Music)

WQXR

By Daniel Stephen Johnson

Bruce Levingston, no stranger to the music of Philip Glass, has finally issued an in-depth, two-disc survey of Glass's piano music, and the result is a surprisingly passionate and spontaneous portrait of the composer. Dreaming Awake (Sono Luminus) is a boldly individual approach to the keyboard works of an American master.

Interpreting the piano music of Glass offers a unique dilemma to the pianist. The construction of the music is often severe and mathematical, the materials lucid to the point of total transparency in order to better showcase the clockwork operation of the rhythms. Instead of plunging forward through a series of contrasting episodes, the music coolly repeats its cadences as if displaying itself in a mirror, allowing the listener to examine the same material from multiple angles.

But at the same time, the harmonic language of the music is undeniably steeped in affect. While the music's transparency and poise pull back towards restraint, the substance of those cadences push forward into warm-hearted sentiment. Should the pianist treat the score like a strict MIDI grid, metronomically obeying every rhythm in order to heighten the transparency of the music? Or should the performer take a cue from those ecstatic harmonies?

From the almost impulsive opening of this record, those first few notes of Glass's magnificently subtle Etude No. 2, it becomes clear that Levingston has given himself over to feeling. This is Glass the Romantic.

In addition to a generous helping of the Etudes, arguably the composer's most substantial solo works, Levingston also offers the rarer title track, his own arrangement of Glass's tuneful film music for The Illusionist, and the earlier Allen Ginsberg hymn Wichita Vortex Sutra.

Even Levingston's stellar choice of collaborator fits the bill. Instead of sampling Ginsberg's own delightfully idiosyncratic reading of "Wichita," Levingston recruits thespian Ethan Hawke, Hollywood's Gen-X embodiment of Romanticism, and Hawke's breathless delivery is absolutely of a piece with the almost cinematic heroics of Levingston's vision for these pathbreaking works.

The New York Times: Shanghai Violin Competition Celebrates Isaac Stern’s Legacy in China

The inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition concluded on Friday after nearly three weeks of intensive performances by 24 young violinists from around the world. Mayu Kishima of Japan was awarded first place, taking home the grand prize of $100,000, the largest single award for an international violin competition.

The Japanese violinist Mayu Kishima was awarded the first prize at the inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition on Friday. Credit: Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition

The New York Times

By Amy Qin

More than 35 years after the violinist Isaac Stern made a groundbreaking visit to China, his legacy there lives on.

The inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition concluded on Friday after nearly three weeks of intensive performances by 24 young violinists from around the world. Mayu Kishima of Japan was awarded first place, taking home the grand prize of $100,000, the largest single award for an international violin competition.

“We were looking for the kind of spark and commitment to music that our father would have embraced,” David Stern, co-chairman of the jury committee, said in a telephone interview from Shanghai.

That Isaac Stern, who died in 2001, now has a competition bearing his name is somewhat ironic given his aversion to such events.

So when the conductor Yu Long, a towering figure in classical music in China, raised the idea of holding a competition about two and a half years ago, “it was not the easiest idea for the three of us to approach,” Mr. Stern said, referring to his brother, Michael, and his sister, Shira. “Our father did everything he could to mentor young musicians in order to avoid competitions.”

Isaac Stern’s dedication to training young musicians was perhaps most vividly captured in the 1979 documentary “From Mao to Mozart: Isaac Stern in China.” The film, which won an Academy Award for best documentary feature, chronicled Mr. Stern’s two-week trip to China for a series of concerts and master classes.

That visit, which came just as China was emerging from decades of self-imposed isolation and political tumult, is credited with having influenced a generation of young Chinese musicians, including Mr. Yu, who recalled sitting in the audience as a teenager during one of Mr. Stern’s performances in Shanghai.

“During the Cultural Revolution, we didn’t have many opportunities to play Western music,” Mr. Yu, now conductor of a number of ensembles including the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, said in a telephone interview. “Then, in that moment in 1979 when Maestro Stern came, we suddenly felt the difference in how we could understand music.”

Since 1979, classical music in China has grown tremendously, with gleaming concert halls being built around the country and some 40 million young Chinese studying the violin or the piano.

Still, Mr. Yu said, “The problem in China, and Asia more broadly, is that the players are more concerned about technical issues.”

So when it came to this new project, both the Stern family and Mr. Yu agreed that they wanted to make a more comprehensive competition that would reward musicians not just for technical ability, but also for all-around dedication to music.

After two years of discussions and planning, the Stern family and the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra came up with a competition structure that David Stern said his father, even with his distaste for competitions, probably would have approved. This meant including elements that were important to Isaac Stern, like chamber music and Chinese music.

For example, contestants in the semifinal round were required to perform two concertos: “The Butterfly Lovers,” a popular Chinese concerto composed in 1959 by He Zhanhao and Chen Gang, and Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 3 with a chamber orchestra (with original improvisation during the cadenza section). They also had to play a violin sonata, as well as the first movement of piano trio by Schubert or Brahms.

The 24 contestants represented several countries, including China, France, Germany, Japan, South Korea and the United States. In addition to the prize money, Ms. Kishima will also receive performance contracts with several international symphony orchestras.

Sergei Dogadin of Russia was awarded the second prize of $50,000, and Sirena Huang of the United States took home the third prize of $25,000. The violinists Zakhar Bron of Russia and Boris Kuschnir of Austria were among the 13 who sat on the jury.

The competition also presented an Isaac Stern Human Spirit Award of $10,000 each to two noncontestants: One, to Wu Taoxiang and Du Zhengquan, who founded the Einstein Orchestra, a middle-school ensemble in China, and the other to Negin Khpalwak, who directs an orchestra for women in Afghanistan, for “their outstanding contribution to our understanding of humanity through the medium of music.”

Most of the funding for the competition, which will be held every two years, came from corporate sponsors, according to Fedina Zhou, president of the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra. The symphony has been expanding in recent years, forging a long-term partnership with the New York Philharmonic and, in 2014, unveiling a new hall where the competition was held.

For many musicians and music lovers in China, the competition represents further validation that China is well on its way to becoming a heavyweight player in the classical music world.

“At last the Chinese people finally have an internationally recognized competition of their own,” said Rudolph Tang, a writer and expert in Shanghai on the classical music industry in China. “It has everything that a top competition should have, like a top jury, great organization, and high prize money.”

“It is like a dream come true,” he added.

The Strad: Shanghai Isaac Stern Violin Competition reveals scores of eliminated quarter-finalists

The inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition has released the scores of the candidates who have failed to make it through to the semi-finals. The violinists are competing for a top prize of $100,000 from 14 August to 2 September 2016.

The Strad

The inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition has released the scores of the candidates who have failed to make it through to the semi-finals.

The move reflects the competition’s commitment to transparency – the scores of all eleven judges (pictured) are revealed, in addition to their vote of ‘yes’ or ‘no’, indicating whether or not they believe the violinist should progress to the next round. The competition intends to release all candidates’ scores as they are eliminated, and of the winners following the final.

Click on the link below to read the latest results in detail:

Last week, the contest named the 18 candidates selected to progress to the semi-finals, taking place from tomorrow 23 August until 29 August. The violinists, aged between 18 and 32, are competing for an impressive grand prize of $100,000.

This year’s jury includes Zakhar Bron, Boris Kuschnir and Maxim Vengerov, in addition to Chinese violin professors Zhenshan Wang and Lina Yu, and co-chairs – conductor and son of Isaac Stern, David Stern, and Professor Vera Tsu Weiling.

In addition to six core prizes – including a second prize of $50,000 and a third prize of $25,000 – there will be two special awards for Best Performance of a Chinese Work and the Isaac Stern Award – given to ‘an individual who is deemed to have made an outstanding contribution to our understanding of humanity through the medium of music’.

For full details visit the SISIVC website.

Gramophone: Anne Akiko Meyers presents an exclusive first listen to Rautavaara's Fantasia

Last December Anne Akiko Meyers travelled to Finland to play Fantasia for Violin and Orchestra, written by the great composer, Einojuhani Rautavaara, which she will be premiering with Michael Stern and the Kansas City Symphony this upcoming season. Sadly with Rautavaara’s recent death, this will be a posthumous world premiere.

Gramophone

Last December I travelled to Finland to play Fantasia for Violin and Orchestra, written by the great composer, Einojuhani Rautavaara, which I will be premiering with Michael Stern and the Kansas City Symphony this upcoming season. Sadly with Rautavaara’s recent death, this will be a posthumous world premiere.

Rautavaara was a legendary Finnish composer who wrote eight symphonies, 14 concertos, and numerous other works for chamber ensembles and choir. He was a protégé of Sibelius, active until age 87, and was best known for writing Symphony No 7, Angel of Lightand the beautifully haunting work, Cantus Arcticus: concerto for birds and orchestra, a piece that took my breath away the first time I heard it.

In my early twenties, I regularly went to record and sheet-music stores, looking through items one at a time in the hope of discovering music that would make the hairs on my neck stand up. It was then I first discovered Rautavaara’s music, and for years, dreamed of commissioning him to compose more music for violin. In 2014, I inquired if Rautavaara, with the wonderful support of Boosey & Hawkes, would be interested in writing a fantasy for violin and orchestra. I was beyond elated when he responded that indeed he would and worked quickly. I received a handwritten draft of the score in the fall of last year, and breathlessly ran to my music studio to play through it.

I think there are similar qualities to the Angel of Light and Cantus Arcticus and Rautavaara’s signature soulful sound permeates throughout the piece, with fluid harmonies and deep moods -much like flowing large movements of water and majestic scenes from nature.

In December, I flew to Helsinki to meet Rautavaara and perform the work for him. We met at the apartment he shared with his wife, and the apartment was flooded with a special light that only seems to exist at the edge of the earth, overlooking the sea. He stood with a walker and was incredibly gentle and kind. Smiling and laughing, we spoke about how Sibelius liked the fact that Rautavaara owned an automobile, as well as his time in New York, studying at the Juilliard School where I also went to school.

After I played Fantasia, he looked at me and repeatedly said, 'I wrote such beautiful music!' We all laughed and agreed. He apologized for what he felt were his lazy bow markings and was so happy that I took the liberty to change the bowings to punctuate the phrasing the way I thought would bring his poetry out best. I was amazed that he made no changes to any notes or dynamics. Everything was in place just the way he wrote it.

Fantasia is transcendent and has the feeling of an elegy with a very personal reflective mood. Rautavaara’s music will live on forever and I thank him from the bottom of my heart for writing a masterpiece that makes me cry every time I listen to it.

Listen to an exclusive preview of Anne Akiko Meyers performing Rautavaara's Fantasia for Violin and Orchestra with the Philharmonia Orchestra and conductor Kristjan Järvi below:

Violinist: Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition Begins August 16

Violinists from around the world arrived over the weekend in Shanghai, where 24 violinists ages 18 through 32 will begin competing Tuesday in the first-ever Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition, which is offering a record-breaking top prize of $100,000, to be awarded when the competition concludes on Sept. 2.

Violinists in the 2016 SISIVC, after a "bow draw" on Monday to determine First Round order.

Violinist.com

By Laurie Niles

Violinists from around the world arrived over the weekend in Shanghai, where 24 violinists ages 18 through 32 will begin competing Tuesday in the first-ever Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition, which is offering a record-breaking top prize of $100,000, to be awarded when the competition concludes on Sept. 2.

Watch for Violinist.com coverage from Shanghai, starting Aug. 24 from the semi-finals.

The competition was named after the famous American violinist Isaac Stern (1920-2001), who broke cultural ground when he traveled to China in 1979 -- a time when China-U.S. relations were tenuous at best. Stern gave concerts and also visited China’s Central Conservatory of Music and the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. The trip resulted in a documentary called From Mao to Mozart, which won an Academy Award in 1980 for Best Documentary Feature.

The competition, two years in the making, will take place at Shanghai Symphony Hall. The 24 competitors represent several countries, including China, Japan, South Korea, France, Germany and the United States. Nearly half of the competitors are from China, with three from the United States. Of the 21 competitors who are not listed as being from the United States, eight of have strong U.S. connections, having studied in the U.S. at places such as the Curtis Institute, The Juilliard School, New England Conservatory, Temple University's Boyer College, Bard College Conservatory and the Aspen Music Festival. One contestant from China is a member of the Oregon Symphony. For full bios of the competitors, click here. (Names of all competitors are listed at the bottom of this article).

Preliminary rounds take place Aug. 16-19, and performances will be available to view afterwards on the competition's YouTube channel. Here is a schedule.. Semi-finals and Finals will be live-streamed on SMG and LeTV -- we'll provide links as they become available.

After preliminaries, 18 competitors will be named semi-finalists. Semi-finalists are required to perform The Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto, which has achieved modern popularity after being written in 1959 by Chinese composers, He Zhanhao and Chen Gang, while they were students at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. Semi-finalists will also play Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 3 with a chamber orchestra (original cadenzas required), a sonata, and the first movement of piano trio by Schubert or Brahms. Competition officials report that all semi-final tickets were sold out within one week of ticketing -- I'd like to think this is a testament to the popularity of the violin in China!

Six finalists will go on to the Final Round, Sept. 1 and 2. Besides the record-breaking First Prize of $100,000 USD; other prizes include a Second Prize of $50,000, Third Prize $25,000 and Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Prizes $5,000 each. Another $10,000 will be awarded for the best performance of "The Butterfly Lovers" concerto; and a $10,000 Isaac Stern Human Spirit Award will go to a non-contestant "in any field and from any part of the world - who is deemed to have made an outstanding contribution to our understanding of humanity through the medium of music."

The competition also has promised winning competitors performance opportunities with various orchestras, including Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, China Philharmonic Orchestra, Guangzhou Symphony Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, and Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

Jury members for the competition are Zakhar Bron, David Cerone, Martin Engstroem, Daniel Heifetz, Emmanuel Hondré, Boris Kuschnir, Elmar Oliveira, David Stern, Maxim Vengerov, Jian Wang, Zhenshan Wan, Vera Tsu Weiling and Lina Yu.

Competitors in the 2016 Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition are:

- Takamori Arai, Japan

- Yu-Ting Chen, Taiwan, China

- Elvin Ganiyev, Azerbaijan

- Fangyue He, China

- Sirena Huang, United States

- Yiliang Jiang, China

- Jee Won Kim, South Korea

- Mayu Kishima, Japan

- Zeyu Victor Li, China

- Richard Lin, United States

- Ming Liu, China

- Kyung Ji Min, South Korea

- Raphaëlle Moreau, France

- Andrea Obiso, Italy

- Dongfang Ouyang, China

- Yoo Min Seo, South Korea

- Ji Won Song, South Korea

- Kristie Su, United States

- Stefan Tarara, Germany

- Xiao Wang, China

- Wendi Wang, China

- Jinru Zhang, China

- Yang Zhang, China

WQXR: Bite-Sized Bytes: Ray Lustig Composing in 15 Seconds

What would you do with 15 seconds? For composer Ray Lustig, it's the perfect amount of time to set up a low-stakes creative lab and ongoing audio-visual experiment. He explains below the inspiration behind his 15-second Instagram compositions, dubbed "composagrams," and how they feed his artistic growth.

WQXR's Q2 Music

What would you do with 15 seconds? For composer Ray Lustig, it's the perfect amount of time to set up a low-stakes creative lab and ongoing audio-visual experiment. He explains below the inspiration behind his 15-second Instagram compositions, dubbed "composagrams," and how they feed his artistic growth.

Last summer I started a new little creative habit: making tiny 15-second compositions with video, a new one, roughly every week, to post to my sleepy little Instagram account. I’d heard that Instagram, formerly dedicated to photos, had recently started hosting video posts, but only up to a 15-second max, and this constraint grabbed my interest. Was it possible to do anything musically meaningful in just 15 seconds? At first I wasn’t sure. Many of my favorite works — Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, and Steve Reich’s Drumming — are over an hour long.

I gave 15 seconds a try. And then another, and another. I started calling them "composagrams" and even started tagging them with the hashtag #composagram to encourage others to do it, too.

Then I started to realize that my little collection of composagrams was serving as a kind of creative lab for me. I was testing new things out, putting new spins on old things, dipping my toe in waters I might not have gotten to in my larger more visible projects, actually expanding my experimentation. Yet at the same I noticed I was following the evolution of my sound preferences with more focus, via these little bits of experimentation.

And now, 15 seconds seems to me kind of perfect. It’s too short to even give a listener time to become bored, yet it’s longer than a gesture, even longer than a phrase. It can be a sentence, a concise one, a to-the-point sentence. While it’s an actual public post of my music, it's low-stakes. If one turns out not so satisfying for me, well it’s only 15 seconds, and I can just start another one.

There's using social media creatively for self-promotion and dissemination of one’s work, but this is different. This is using it as an actual creation platform, music written just for the consumption style of the social media feed. And it's not simply an opportunistic niche. There's something to casting work into the public light regularly that helps you hear it differently, gives you that crucial new perspective on something we artists spend all our time so close to, our own work.

Composers out there, give it a try if you don't believe me. And use the hashtag #composagram so that people who see one and like it can check out a few more. Instagram changed its limit to 60 seconds, but that's an eternity in social media time, so discipline yourself to keep it to that perfect little 15-second window, that bite-size, to-the-point little sentence. If you can't decide what to do, do a bunch of them so you don't have to decide. Make it a habit that feeds your artistic growth. — Ray Lustig

Born in Tokyo and raised in Queens, N.Y., composer Raymond Lustig is deeply inspired by science, nature, and the mind. Also a published researcher in molecular biology, he studied cell division, the cell skeleton, and cell polarity at Columbia University and Massachusetts General Hospital before beginning his graduate studies in composition at Juilliard, where he completed his MM and DMA degrees.

Strings Artist Blog: Cellist Julian Schwarz Discusses Is Talent Inherited?

It is true, that there are moments in music when one cannot simply deny the existence of something special––something undeniable, and sometimes inexplicable. And there was a certain moment in [cellist, Julian Schwarz's] life when the case for inherited musicality made an extremely compelling case.

Strings Guest Blog

Julian Schwarz

Having been born into a multi-generational musical family, I was often told “it’s in your genes” or “it must run in the family.” This always struck me as odd, especially as a youngster, as I was spending hours in the practice room honing my craft. If it were all in my genes, why was I working so darn hard anyway? If we take this one step further, the whole idea of talent is a rather abstract idea in the first place. I recently sat on a jury for a competition in New Jersey when, after a particularly gifted student auditioned, a colleague on the jury said, “I always aim to dispel the notion that talent actually exists, but after hearing that, it is a hard angle to defend.” It is true, that there are moments in music when one cannot simply deny the existence of something special––something undeniable, and sometimes inexplicable. And there was a certain moment in my life when the case for inherited musicality made an extremely compelling case.

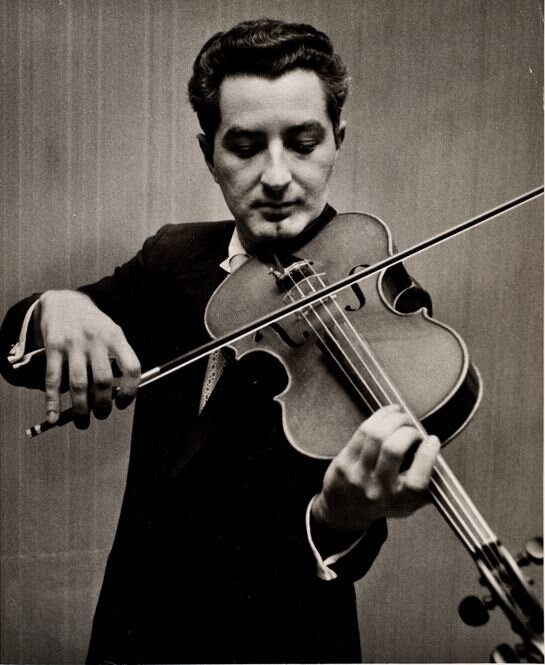

My maternal grandfather, Sol Greitzer, was a violinist born in the Bronx in 1925. After returning from his service in the United States Army, as a runner in the Battle of the Bulge in World War II, he found the high frequencies of the violin too piercing for his artillery sensitized hearing. He switched to the viola, and quickly ascended the ranks of the NBC Symphony and the New York Philharmonic. In 1972 he became the principal viola of the NY Phil under Pierre Boulez.

His premature passing in 1989 took him from this earth prior to my birth, and I neither had the chance to meet him nor to hear him play. As a young boy I was told frequently by family “he would have loved you,” which, though sentimental and sweet, made me yearn to have known him. This sentiment became stronger in the family as my deep love for the game of baseball grew (let’s go Mets)—as he was a fan of the game and always wished for a son among his three daughters.

My grandfather Sol passed before the age of instant recording, so very little evidence of his playing remains to this day. It was not until I was 17 that I heard even a note. By this time my musicianship had developed to a certain point, and my first string of concerto appearances had come to pass. My mother had received an old live radio broadcast of my grandfather playing the Stamitz Viola Concerto with the New York Philharmonic and Zubin Mehta on the podium. I was beyond excited to hear his tone, phrasing, and overall style. After putting the disc in my portable CD player, my sense of expectation built through the opening tutti. Every cadence raised my heart rate as I was ready to hear what I had been missing for years.

Finally, his warm, rich tone entered and I was taken aback. I started to cry. I could not believe my ears. His phrasing was elegant, his vibrato constant, his portamento tasteful yet old fashioned; this was the playing I always envisioned for myself. This was the playing that more closely resembled mine than any cellist or string player I had heard up to that point.

Without ever hearing him, without ever meeting him, and without ever feeling his presence, I had grown up to sound just like him––in every way. There were subtle differences, but the similarities were undeniable.

Who knows if musicianship is inherited, but at that moment I felt connected to a man I never knew, and so wished I had.

The Strad: Violinist Isaac Stern in China

Captured in the 1979 Academy Award-winning documentary From Mao to Mozart, Isaac Stern had a transformative effect on China's classical music scene - more than he ever knew. Today his legacy lives on with the launching of the Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition. Nancy Pellegrini talks to son David Stern and some of the film's stars about the 'Stern effect.'

The Strad

Excerpts from Violinist Isaac Stern in China

Captured in the 1979 Academy Award-winning documentary From Mao to Mozart, Isaac Stern had a transformative effect on China's classical music scene - more than he ever knew. Today his legacy lives on with the launching of the Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition. Nancy Pellegrini talks to son David Stern and some of the film's stars about the 'Stern effect.'

The year was 1979. Emerging from decades of isolation and political turmoil, China had just opened its door to the West, and legendary violinist Isaac Stern was hoping to peek inside. The result was the Academy Award-winning documentary From Mao to Mozart, which chronicles Stern's visit to music conservatoires in Beijing and Shanghai. This brilliant, touching film gave Westerners an insight into life behind the Bamboo Curtain, while igniting Chinese careers and changing music in China forever. The Stern family has continued its association with the country, but it is China that will never forget. August 2016 was the start of the inaugural Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition (SISIVC), which organisers hope will help to inspire and motivate a new generation of musicians.

Isaac Stern had long used his musicianship to build bridges and foster talent, touring the Soviet Union in 1951, helping save New York’s Carnegie Hall from destruction, and mentoring a host of promising young players including Itzhak Perlman, Yo-Yo Ma and Pinchas Zukerman. While some claimed his extra-musical efforts were hampering his own skills, music and humanity were, to him, simply extensions of each other. China opening up to the West was his next logical frontier.

However, when even US diplomat and close friend Henry Kissinger couldn't help him gain entrance, Stern had a strategically casual dinner with China's foreign minister, and an evening conversation became an official invitation. The film was also a product of family friends, but the Sterns insisted it be about China, not them. 'Even when I see it today, that's what impresses me; it was so unpretentious,' says David Stern, whose clear admiration for his father still resonates. 'It wasn't a grand master delivering the word. My father had lived a life that very few people can live, and all he wanted to do was share it.'

Wang is certain that Stern brought about a seismic change in China's music scene. 'He showed us, he told us, he demanded from us that music was all about expressing yourself,' he says. 'The content is more important than the presentation - and in those days in China, presentation was everything.' China had talented teachers, he recalls, but the general trend was to study the form and imitate the West. 'We did not have the confidence nor the tradition to say that music is only a tool to express yourself,' he recalls. 'Isaac Stern said "I don't care how you play, but you have to say something."'

Maybe even more than music, Stern was known for mentorship, which is why the family eventually allowed his name to be attached to Shanghai's newest competition. But they had concerns. 'This was not an easy birth because my father principally believed that music is not a competition,' says David Stern. In fact, Isaac had avoided the competition circuit and nurtured talent so that others could do the same. But times have changed. 'An Isaac Stern of today would not have the influence he did then; the music world was smaller, moved slower, had more patience,' he says. 'Today it is increasingly difficult for young musicians to get their chance.'

Launched by the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra (SSO) to discover talent and honour Stern's legacy in China, the SISIVC has been designed with Stern in mind. This means that, although virtuosity is rewarded, musicianship and development will come first. David Stern himself insisted on a chamber music round, and organisers will introduce the most promising candidates to top music agencies. The jurors' scores and comments will be released to the public, so that candidates can receive further feedback. And the SSO and principal sponsor China Pacific Insurance's musical outreach programme 'The Rhythm of Life' will allow competition laureates to give concerts with the orchestra at venues across the country. 'The programme is entrusting young musicians with enriching the life and culture of urban centres around the country,' says SO president and SISIVC executive president Fedina Zhou, 'fulfilling its core philosophy of bringing music to the ears of many, and turning "soloists" into "musicians".'

Tsu, who serves with Stern as jury co-chair, feels that Shanghai - and indeed China - is due for an international competition of this scope, and is already excited about the contestants' high level. Wang feels there is no better homage to Stern. 'He cultivated and propelled so many new careers; some of the greatest performers alive are performing because of him. There are only one or two in the history of music like that. We need to keep his legacy alive.' Li also sees overwhelming positives, and points out that when it comes to music in China, SSO music director Long Yu has the Midas touch. 'Everything he organises blossoms so much,' he says. 'With anyone else I would be sceptical, but with him I have confidence that this will be great.' He also says that while many competition winners disappear after a handful of concerts,' Yu's myriad orchestra connections will be a boon for the winners. 'This will build a concrete career for these young soloists.'

But the most important factor is to keep Isaac Stern's legacy, and the From Mao to Mozart spirits alive. 'My father was one of the few who managed to elevate everyone around him,' says David Stern, 'whether it was a conversation in a restaurant or playing a violin concerto.' And this will indeed be a family affair. The violinist's daughter Shira will be presenting the Isaac Stern Award, granted to the person in any field, from any country, who best uses music to improve society. His son, conductor Michael Stern, will conduct the orchestra for the final round, before working with Yo-Yo Ma on a 2017 youth festival in Guangzhou. David Stern has been conducting in China several times a year since 1999, when he led his father and other film alumni (including Wang and Tsu) in a 20th-anniversary From Mao to Mozart concert. Today he runs an annual Baroque festival in Shanghai and teaches vocal masterclasses. He repeatedly insists he is not following in his father's footsteps, saying, 'I just believe in it and I love doing it.'

But perhaps the best takeaway is Isaac Stern's address at the end of the film: 'If you do not think that music can say more than words, that there can be no life without music; if you do not believe these things, then don't be a musician.' Says David Stern of his father's advice. 'It's the strongest defence of arts I've ever heard.' Words to live by indeed.

Greensboro News and Record: Music review - Gerard Schwarz and Brahms highlight EMF Chamber concert

By Jackson Cooper

The communal feel of attending an EMF concert can be equated to the spirit of a Fourth of July barbecue. Enthusiastic grins and reconnecting with old friends is a common sight. The audience chatters like children in anticipation for the show they are about to witness.

This created an exciting buzz around the evening of chamber works presented by EMF faculty and guest artists as the final installment of the Monday chamber series, held Monday night at UNCG Recital Hall.

The evening opened with Mozart’s Oboe Quartet in F major, performed by soloist Katherine Young Steele on oboe and accompanied by violin, viola and cello. A welcoming start to the program, Mozart’s piece is a more traditional sounding chamber work. All four instrumentalists succeed in controlling Mozart’s sudden dynamic changes nicely. In multiple sections, they used slight tempo changes to heighten the expressiveness of the piece. Steele’s oboe playing was lyrical throughout, gracefully adding to a richly satisfying dialogue between the four musicians.

After the Mozart appetizer followed Boccherini’s Guitar Quintet performed with Jason Vieaux on guitar accompanied by viola, two violins and cello. Living in Madrid for most of his life, images of Spain sprung to mind in the opening moments of Boccherini’s piece. Vieaux played Boccherini’s shifts between accompanist and solo lines with grace and ease, controlling dynamics masterfully.

During the final movement, the aptly named “Fandango,” cellist Julian Schwarz provided aerobic and percussive playing that seemed to captivate the audience. He even took a short break during the piece to play on castanets, one of the two percussion instruments the program notes mention (the other, a sistrum rattle, was sadly absent from this performance). The inspired performing, with special shout-outs to Schwarz and Vieaux, brought the audience to its feet for three ovations.

Following intermission, EMF favorite Awadagin Pratt joined the faculty for a moving performance of Brahms Piano Quintet in F minor. Much darker and undulating in tone than other Brahms chamber works, the piece introduces in a musical idea which it riffs and rhapsodizes over the course of the opening movement, creating a dark tapestry of sound different from for instance, the playful Mozart from the first half. The tone of the first movement is one of uncertainty, creating a feeling of suspense as a listener.

The Andante section is a lighter detraction from the first movement, and Pratt and his cohorts made the shift in tones seamless to create a romantic intermezzo. A rousing Scherzo section followed, containing some ensemble glitches. Despite these, the climactic moments of exuberance were well captured by the players.

The Finale, a mirror to the first movement in contrasting tones, pushed the quintet into its most passionate playing, as if the musicians had been held back for three movements and now, they are able to let loose. Brahms’s sudden shifts in mood were thrilling to experience. By the time they reached the final chord, the audience did not seem to want it to be over. It makes you wish every Monday could be this inspiring.

The Strad: Review of Israeli Chamber Project's NYC Concert May 5, 2016

The Strad provides a glowing review of Israeli Chamber Project's concert at NYC's Merkin Concert Hall on May 5, 2016.

The Strad

Review by Leah Hollingsworth

The Israeli Chamber Project played with character and aplomb in this concert at Merkin Hall. The dense score of Weber's Clarinet Quintet was performed with a rich depth that may have seemed a mire overbearing but which conveyed a confident and charismatic energy.

André Caplet's Conte fantastique began with an arresting reading of Edgar Allan Poe's The Masque of the Red Death - on which the piece was based - by actor Michael Cumsty. A sinister entry by violist Dov Scheindlin and cellist Michal Korman gave way to a tumultuous and brilliantly executed performance by all members of the quintet (string quartet and harp). Complex rhythms and myriad extended techniques were well executed and embodied the disturbing and dramatic nature of the text effectively. The piece reached a frenetic climax that verged exhilaratingly on losing control. The ensemble playing was fantastic and harpist Sivan Magen was particularly vibrant.

Although by the end of Brahms's Piano Quintet the string players were obviously fatigued, their performance of this marvellous music was as passionate and heartfelt as the earlier works. Korman's introduction to the finale's theme was absolutely stunning - light but not trite, and played with an optimistic sound tinged with sadness and depth.